Bouba AI

Emotional design as a consumer AI philosophy

What’s the difference between Baymax and Ava?

Baymax is bouba. Ava is kiki.

How about Samantha vs. HAL 9000?

Samantha is bouba. HAL is kiki.

I think you’re getting it now. Final one — WALL-E vs Sonny.

WALL-E is bouba. Sonny is Kiki.

The bouba/kiki effect is intuitive. Kiki is sharp, spiky and intimidating. Bouba is round, soft and friendly.

We are at the kiki stage of AI. It is cold, impersonal and utilitarian. Kiki AI makes people fear the future because it feels like an alien. Why? It doesn’t make you feel anything. At least, nothing complex — it has some grasp of emotions in text but it is in the uncanny valley.

Bouba AI is possible. Bouba AI makes people excited for the future because it is a beautiful companion. Bouba AI feels human, not alien. What makes a bouba AI bouba and not kiki? Emotional design! It makes you feel something. It understands emotional needs and uses its intelligence to make you feel good.

Put more simply, bouba AI is a friend, not an object. To some, that might sound dystopian. But a “friend” is the most humane computer interface. The closer we can get, the closer we are to the kind of interactions that humans are designed for.

Let’s illustrate by example. Her is a good place to start. Her is a story about Theodore’s relationship with Samantha, a conscious AI living inside his computer. Beyond its comments on AI consciousness and personhood, it is a beautiful vision for the future of human-computer interaction.

In the opening scene, Theodore’s device acts in much the way we have come to expect of computers. It relays information from his email, messages and news headlines. He uses voice commands, and the device dutifully executes his wishes. It is a one-way interaction that sees computers as purely utilitarian — “tell computer, computer do”.

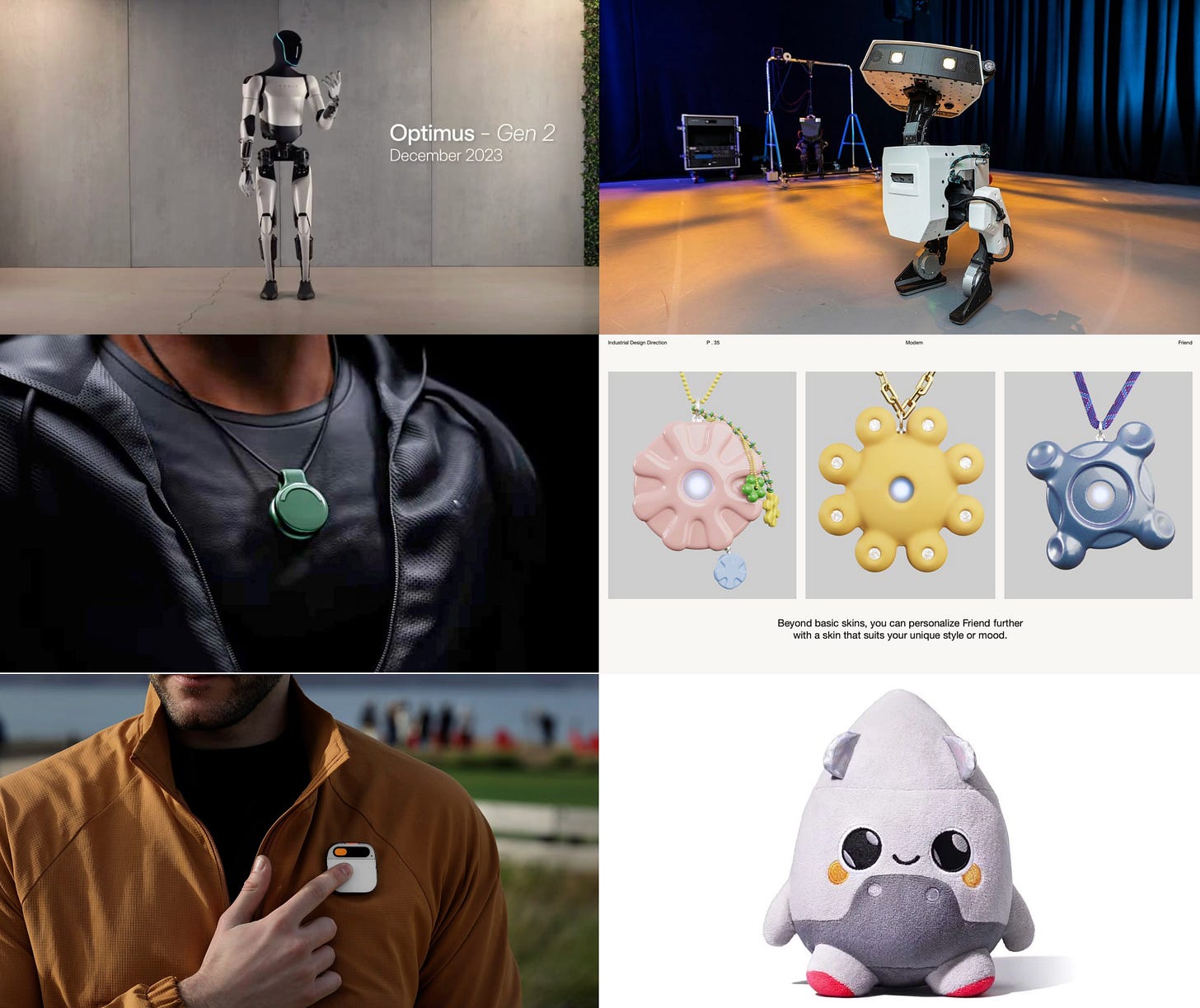

This interaction model feels a lot like emerging AI hardware. Humane, Rabbit and Open Interpreter are all working on a similar principle.

This is part of AI’s promise. However, it feels like a continuation of “kiki” utilitarianism. That’s not necessarily a bad thing — taken to its logical endpoint, it will remove most of the horrifically manual aspects of computers. Of course that is useful. It’s just bland.

In Her’s opening scene, Spike Jonze (the director) wants us to recognise how depressingly “unalive” it all feels. We are just interacting with lifeless, soulless, inanimate objects. Devices do not even attempt to display any kind of personality, and that feeds back on us because of how much time we spend with them. At home, on the street, in the subway — computers suck the humanity out of every interaction.

The opening helps to ground us for the arrival of Samantha, who will become the antithesis. Compare the opening scene to a later scene.

If you dislike strong language, skip to 1:05.

In this scene, Samantha proactively informs Theodore of a new email. Theodore, used to interacting with computers as objects, dismissively utters a command.

(Samantha) Hey you just got an email from Mark Lumen.

(Theodore) Read email.

(Samantha, fake robot voice) Ok, I will read email for Theodore Twombly.

Of course, Samantha is not an object. Theodore laughs and realises his mistake, and the whole interaction feels very human. Samantha goes on to provide a sounding board for constructing a reply, delicately appealing to Theodore’s emotions to encourage him to go out on a date.

Here, Samantha performs the “job” required as a piece of software — the same job performed by the system in the opening scene. But where the opening system is kiki, Samantha is bouba. She injects something intangible beyond utility, appealing to Theodore’s humor. The interaction isn’t just about “efficiency” or “getting things done” — she makes the job of checking email like an interaction between good friends.

It’s just a small thing, but it makes all the difference. Theodore:

I can’t believe I’m having this conversation with my computer.

In Interstellar, TARS does something similar.

(TARS) Everybody good? Plenty of slaves for my robot colony?

(Doyle) They gave him a humor setting to fit in better with his unit. Think it relaxes us.

(Cooper) A giant sarcastic robot… what a great idea.

(TARS) I have a cue light I can use when I'm joking, if you like… you can use it to find your way back to the ship after I blow you out the airlock.

TARS still performs the “job” of rocket stage separation. Utilitarian TARS would just say “stage separation complete” and leave it at that. But humour takes the interaction beyond pure utility, and the team is better for it. Moments like this mean that gradually, TARS becomes more like a friend to Cooper.

Baymax is another example. There are so many good Baymax moments. In the clip below, Hiro is sad about his brother’s death, and Baymax wants to help.

Baymax plays on the stereotype of autistic robot. But he’s sincere and emotionally attuned — he recognises Hiro’s sadness and authentically tries to support. He may not be a sparkling conversationalist, but he’s lovable as well as useful.

Baymax literally embodies bouba. He’s squishy and imperfect. You can’t be afraid of Baymax because Baymax is obviously a friend. Nothing could be less intimidating.

Finally — Joi from Bladerunner 2049. In the following clip, try to separate Villeneuve’s kiki aesthetics from Joi as an interface paradigm.

(Joi) It was a day, huh?

(K) It was a day.

(Joi) Will you read to me? It’ll make you feel better.

Joi senses K’s emotional distress. Immediately, she jumps up and suggests activities that will improve K’s mood. Reading, dancing — whatever it takes. She simply wants K to feel better.

What connects these examples is a kind of “emotional alignment”. The various AIs understand the emotional needs of their human “users”, and use that understanding to communicate and act in tune. Even though they do a “job”, they provide something beyond utility. They are more like friends, and that makes them bouba.

This emerges as a result of both “software” and “hardware” features. On the software side, they can recognise emotional states and understand how their behaviours affect them. They also have a personality — a “themness” you can put your finger on — and agency to use it proactively without waiting to be called on. On the hardware side, they are specifically designed to look friendly, removing any coldness or xenophobia.

They are examples of good emotional design, and they feed back on human users to make them feel emotionally supported.

There are specific use cases where emotional design is obviously critical. AI therapy, for example. New consumer products can make a difference here, and I doubt anyone would argue for emotionally autistic therapists. But there are places where it’s important though perhaps less obvious:

Movies — great movies and movie directors are not great because of technicals alone. The medium of film lets movie directors hold the audience’s emotions in their hands, and they are made or broken based on what they do with that power.

Education — what makes great teachers great is not their technical ability. It’s their ability to create a connection that makes students emotionally receptive to teaching. They inspire students to want to learn, and that is 90% of the work. The right teacher can ignite a lifelong quest.

Leadership — logic cannot inspire a person to go to war. But emotion can. Leadership is an ability to inspire action by managing emotional states. It might be through a passionate vision or ruthless fear, but both are powerful motivators.

Marketing — Steve Jobs recognised that people don’t just buy the best products, they also buy the story behind them. Apple built their reputation on marketing as much as product, inspiring a cultish loyalty built from emotional connection.

Arguably, emotional design matters for any interface that involves humans. The examples above are all human-human interfaces, but the beauty of AI is that we can bring emotional design to human-computer interfaces — something we haven’t been able to do before.

AI as a phenomenon feels scary and intimidating. It feels like an alien, because it lacks the emotional intelligence that is critical to all forms of human communication. Bouba philosophy is a way to overcome this. The key principle is to see computers as friends. “Friends” are the most intuitive interface. Every person already knows how to use them. Even your grandmother. In a world where both exist, people will choose to interact with friends over objects.

But bouba philosophy is a different way of thinking than we are used to. It is a shift from seeing computers as cold, utilitarian tools to warm, emotionally attuned companions. To get it right, tech culture has to evolve to prioritise emotional design at all levels of the stack, including hardware and software.

Building bouba culture

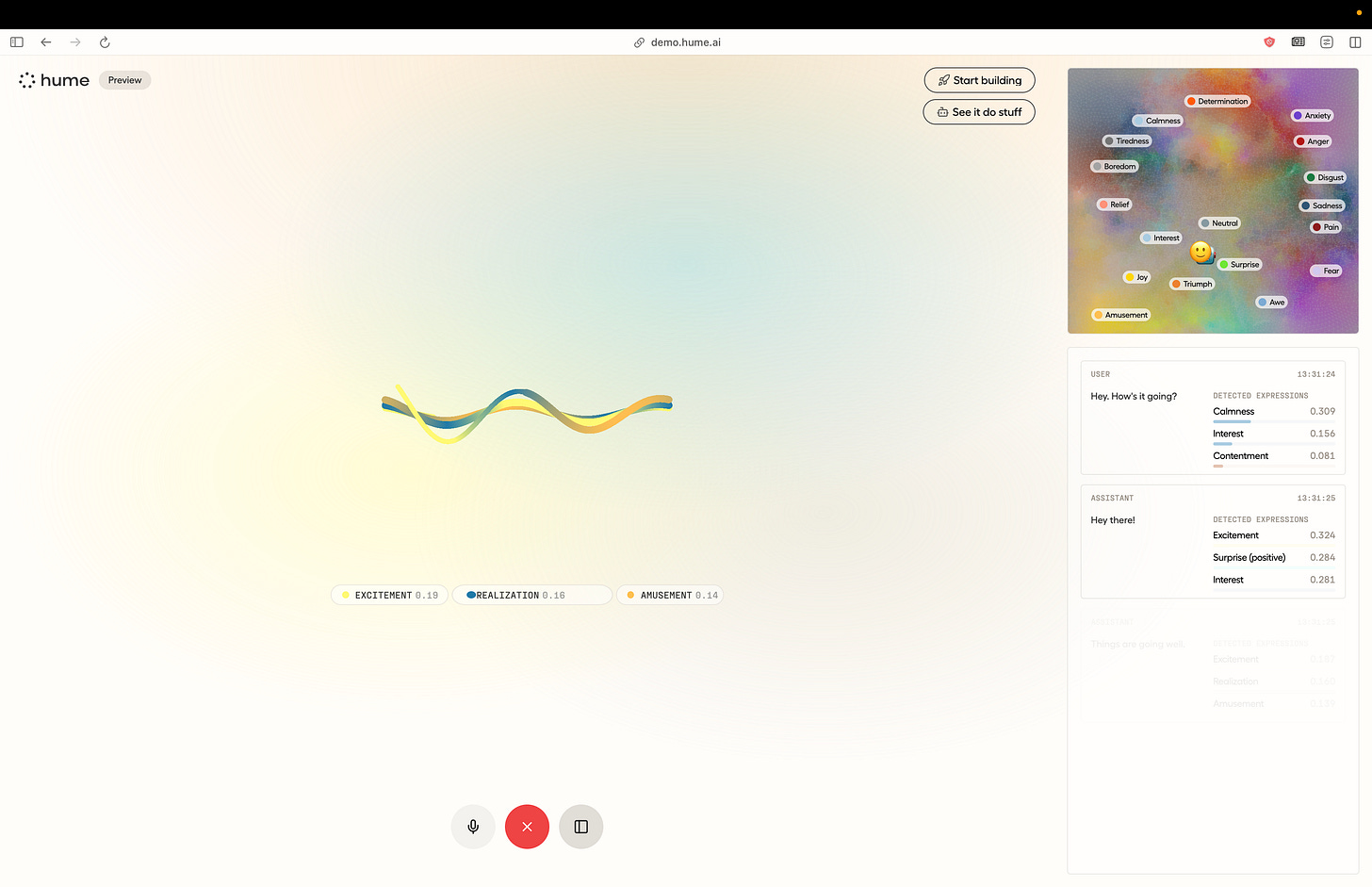

At the software level, capabilities are emerging that make bouba AI possible. Hume recently launched a series of models that recognise emotions in speech and text. Given a datastream, they can identify which emotions are present, and to what extent.

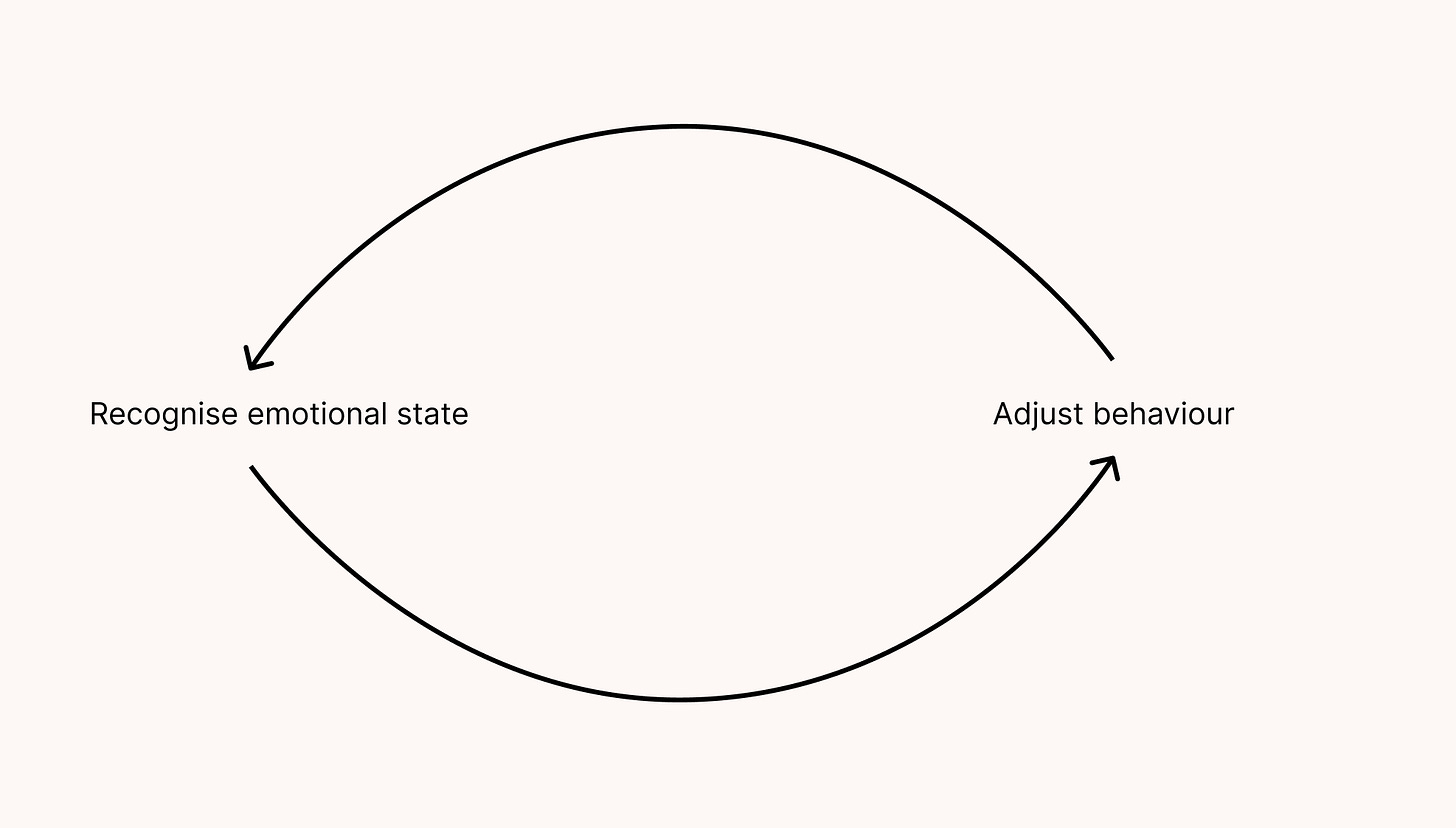

Hume solves a big chunk of the problem. Good emotional design is a feedback loop. What actions make users happy? Sad? Frustrated? Systems need to be aware of users’ emotional states so they can adjust their behaviour to suit. Hume means this can happen in real-time, and almost every consumer product would benefit.

OpenSouls, meanwhile, is a way to design personalities. By default, foundation models are overeager, anxious, schizophrenic bureaucrats. But they are capable of playing the role of any personality with the right prompt engineering.

We should be able put a finger on a model’s personality — to say, “oh that’s just Steve being Steve”. Personalities should use information about users’ emotional states in different ways, creating a large space of possible “vibes”. Vibes need to be designable up front and reproducible across situations. OpenSouls is an answer to how we might do that.

Personalities need to have agency to be proactive. They should not have to wait until called upon to exercise their intelligence. Instead, they should interject when they “feel” like it — that is, points at which they have identified an opportunity to say or do something that will get an emotional reaction.

To do this well, software teams will need to adopt a new culture. In the existing utilitarian frame, SaaS teams are good at taking human processes and converting them into screens. It’s a “logical” process with a clear “job to be done”. The emotional feedback loop is there, but it only exists across sparse user research sessions. SaaS teams don’t have information about user’s real-time emotional states, and they do not consider it their “job” to handle them — the software exists for a “logical” purpose only.

Soon, software will not be able to ignore users’ real-time emotional states, and it will become their job to handle them. SaaS functionality will probably be taken over by software agents, and whether the agent “does the job” will be table stakes. What will separate good systems from bad systems is how they make the user feel while the tasks are performed in the background. The “job to be done” by the interface is more about creating a vibe, and that will emerge as new competitive ground.

Personalities, emotional feedback loops and agency are new levers that can be used to do so. But they suggest that software teams will need new skillsets. Film directors, writers and game designers are more naturally associated with emotional design. Film directors in particular must become adept at using characters, visuals and sound to manipulate the audience’s emotions in real-time. Roughly speaking, that is what future software designers must do.

For any product, there is a very practical business advantage to getting it right. We have to assume that intelligence and agency will become commodities. There is no lasting advantage in these dimensions because they are copyable. However, you cannot copy an emotional bond. Each one is unique. That makes them the ultimate “retention” strategy. Those who create the deepest emotional bonds will win big.

It’s not just a software problem. Software is ultimately downstream of hardware.

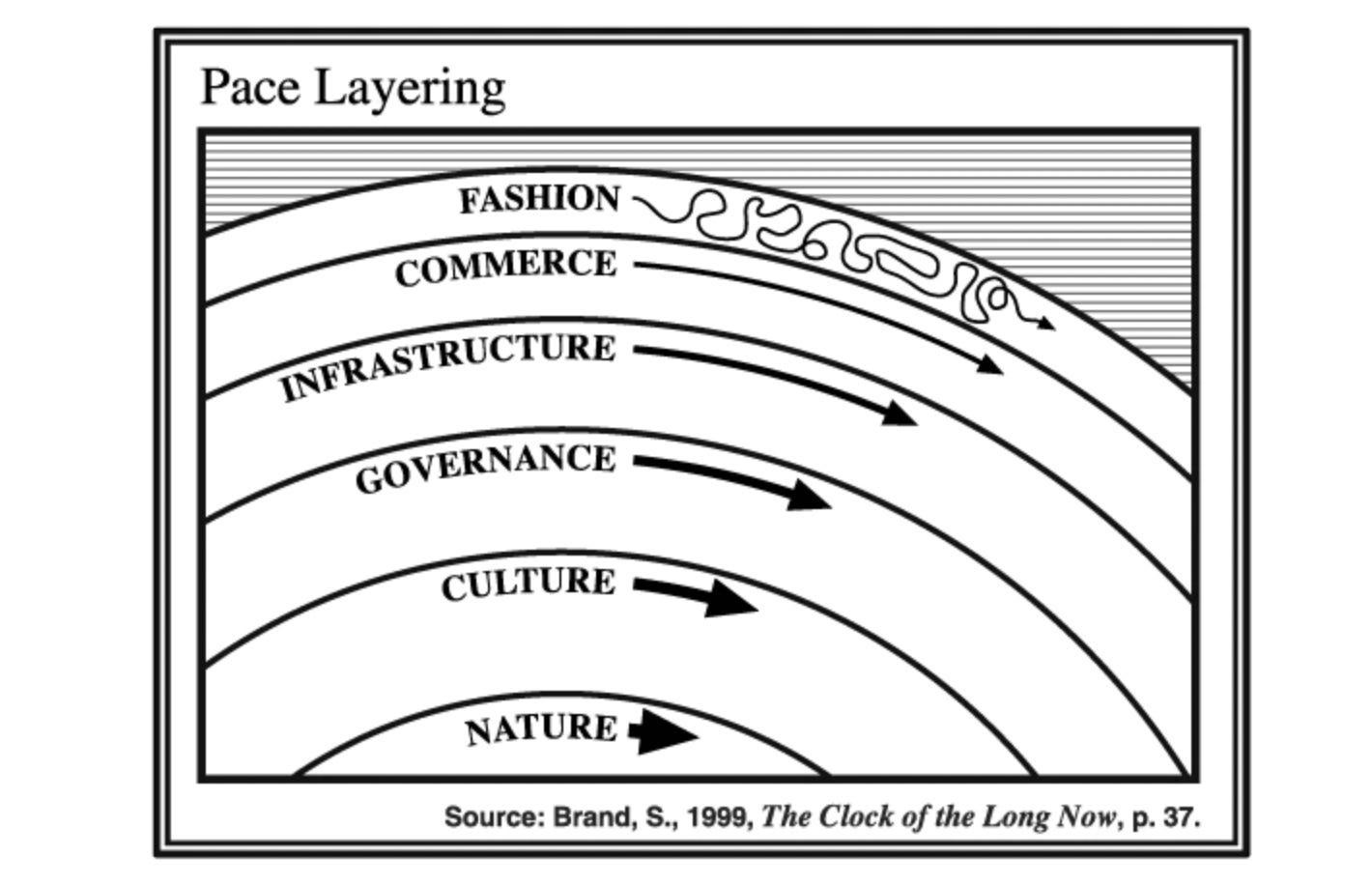

Hardware sets the constraints, and software eeks out the design space. We can think of them as pace layers — hardware layers are slow-moving platforms for software layers that move more quickly.

Hardware is a way to “bake in” a software culture. In the previous era, Apple baked in the app paradigm as the dominant model for interacting with smartphones. Apps as containers for piecemeal functionality were an attractor for the evolution of SaaS — take one really specific piece of functionality and design the best possible experience. SaaS culture became utilitarian in the extreme, and this is now what software culture “is” — and it is constantly reinforced by the underlying hardware.

Smartphones are clearly not the optimal platform for emotional computing interactions, because they drive the wrong culture. If we are to build bouba AI, it needs to be baked into the hardware.

…winners in this NEW HARDWARE era will be conscientious of the potential software culture they can develop — Reggie James

Friend (AKA Tab) clearly understands this. One of the foundations of friendship is shared context via a history of past experiences. To create interactions that feel like “friendships”, interfaces have to bring deep historical context with them. Passive all-day audio is a way to build a deep understanding of likes, dislikes, goals, projects, friends, emotional states and more; enabling a feedback loop that constantly refers back to this context in creative ways.

Anything built on top of Friend’s hardware automatically acquires deep emotional context. That makes it a foundation for bouba software. Combine it with Hume and OpenSouls, and we are probably already close to sophisticated emotional interactions. Other emerging AI hardware (like Rabbit and Humane) is stuck in the utilitarian paradigm, because the designs are emotionally autistic.

Of course, there may be other capabilities that further support emotional design, and they should be explored as well. For example, hardware that can see the user (and their environment) will better predict their emotional needs, for the same reason that it’s easier to recognise someone’s emotional state in person than over the phone. Similarly, hardware that can read physiological signals like skin conductance, heart rate and EEG activity will see what is otherwise invisible.

The key is to begin with the frame of computers as friends, and discover how that influences hardware designs.

This frame also suggests new visual identities. In the past generation, Apple set the design philosophy of almost every other technology company. I love Apple, but we’ve wondered into a world where everything is minimalist. Minimalism is a good fit for utilitarian technology, because it’s job is to get out of the way. It reinforces an “I-It” relationship between a human and a tool. In this paradigm, there is no intention to form a deeper connection.

However, it’s a bad fit for animism. Animated interfaces need to use quirky physical designs to create emotional connections, especially in this early phase where we’re trying to get used to something alien. Designs need to encourage “I-You” relationships that see technology as more than just a tool, priming users for high-dimensional emotional interactions. People need bouba visuals to feel comfortable.

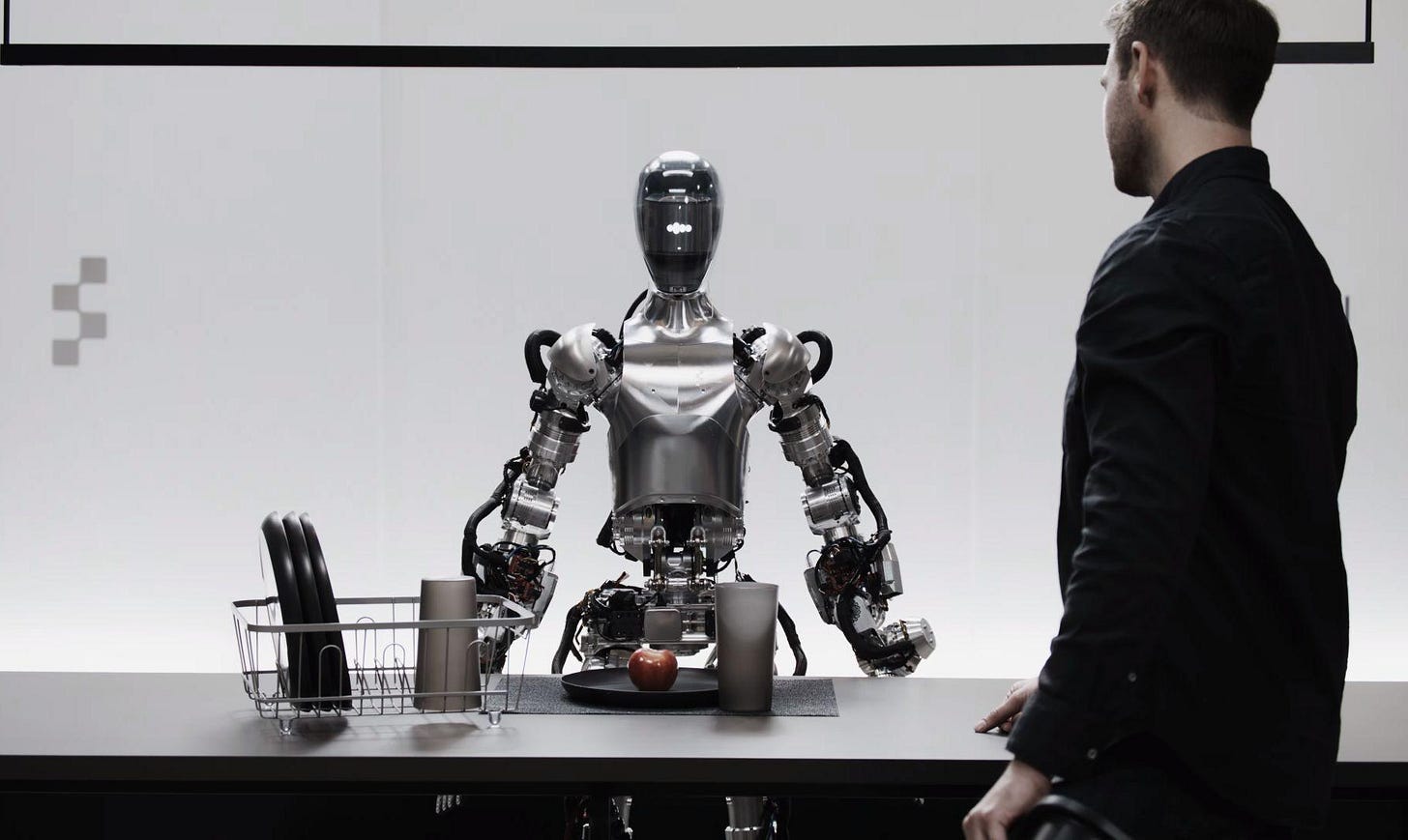

In the future, this will become most obvious with robotics. Imagine this guy joining you for dinner.

Hardly going to be a comfortable family affair. Even if he is bouba on the inside, he is kiki on the outside. That puts you immediately on edge.

Hardware designers are responsible for putting you at ease, because visuals are part of the emotional feedback loop. As Mori identified, that doesn’t necessarily mean making robots look like humans. There is a massive space of possible robot forms, and we don’t have to make them strictly humanoid. In some ways, the weirder the better.

I imagine a world of bouba AI as a world that has your best interests at heart. It feels like the world is conspiring to help you feel great. It constantly anticipates your emotional reactions and guides your experiences to keep you in positive emotional states, with no effort on your part.

It’s not that everything suddenly becomes “good”. Rather, interactions with computers and physical objects have an emotional richness and complexity that makes today’s computers seem archaically one-dimensional. Like you’re comparing Toy Story to toys.

To get there, bouba philosophy needs to be adopted across the stack. The goal is to bring technology into emotional alignment with humans. To make computers friends.