Franchise factory

Hollywood risk appetite in an era of escalating costs and declining revenues

Filmmaking used to be about original stories. In the 1990s, studios regularly bet hundreds of millions of dollars on new ideas that audiences had never seen before. Today, those same studios spend even more money remaking what worked yesterday, churning out an endless chain of sequels and remakes.

How have Hollywood business models influenced this trend, and is there any hope of a reversal?

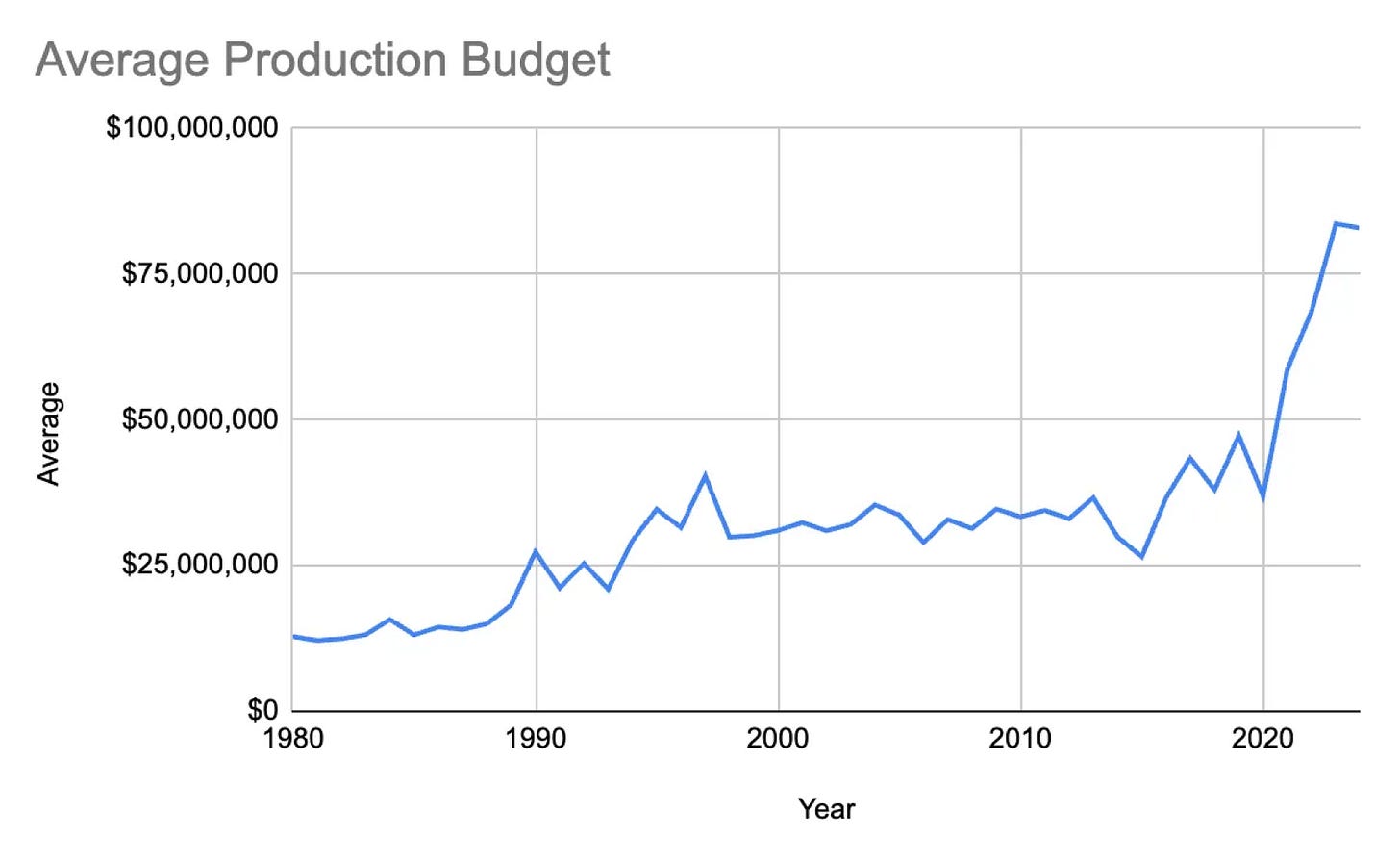

Making films has become very expensive

Production budgets have been steadily increasing over the past 50 years. As of 2023, the average production budget for a Hollywood film was ~$80M.

This figure actually underrates the cost of creating top-tier films, with most spending more like $100-150M on production. Animated films can push the cost even further past $200M. There’s hardly an upper limit — it can go way beyond this.

In any production scenario, the studio usually spends roughly the production budget again on distribution. So, the actual all-in cost to produce and distribute a top-tier film often grows beyond $200M. This is a significant amount of money even for big companies, and naturally, it creates a lot of risk.

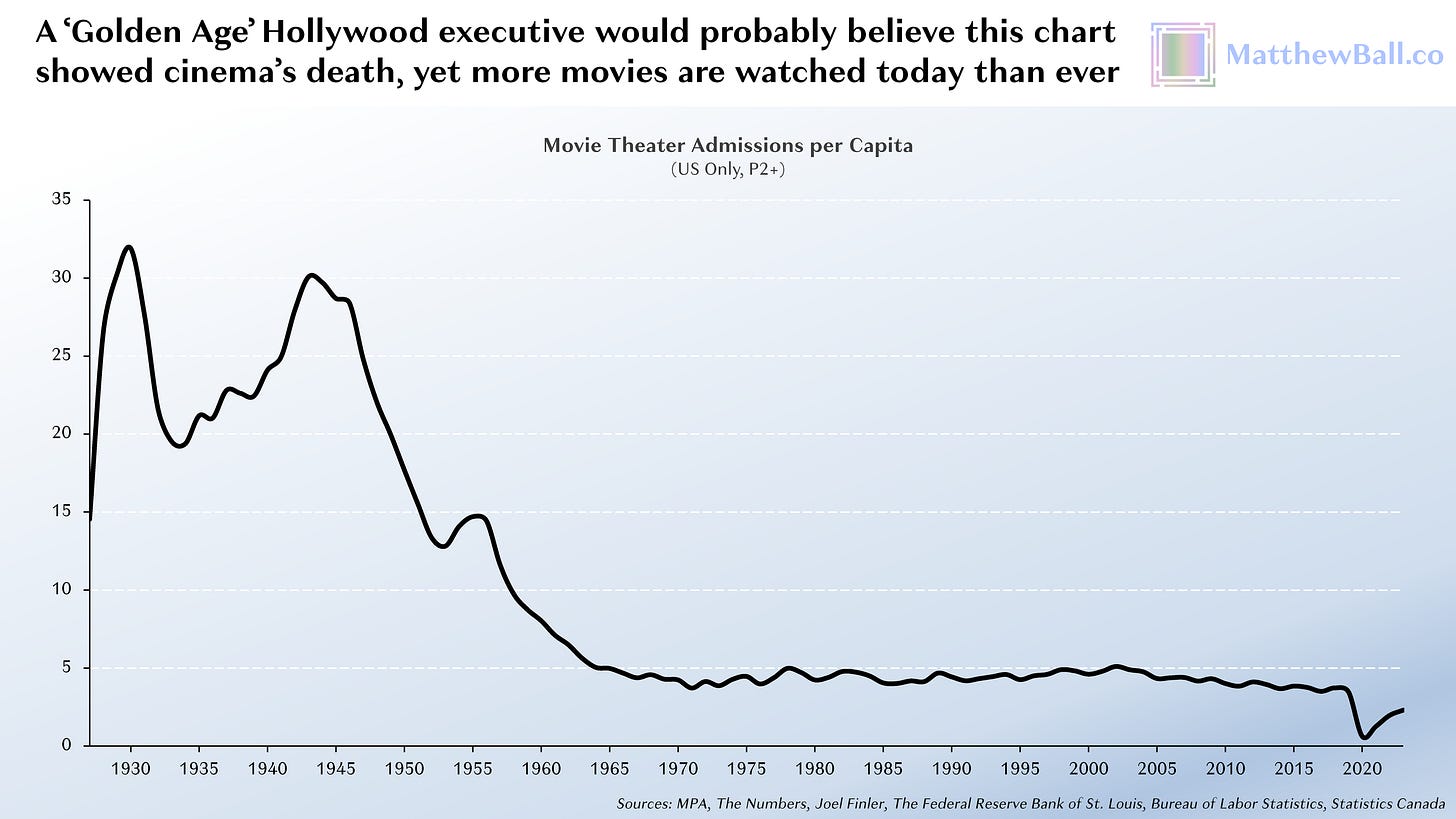

Revenue models for new films are concentrated at the box office, where sales are declining

Like any business, studios must make a profit. In recent years, that has become more difficult with the decline of theatre ticket sales and DVDs/blu-rays.

From the late 1920s to about 1950, average theatre admissions per year reached as far 30, with many people going to the movies at least once a week. There were no TVs and no home movies, so if you wanted to watch a film, you had to go to a theatre. Theatre attendance began to decline significantly in the 1950s as home television sets became more common, and has continued to decline on a per capita basis since 2000.

In the same time window, box office revenues have declined on an inflation-adjusted basis. Meanwhile, the number of films released each year has continued to increase. This means that there are more films competing for the same pot of revenue.

From about 1990-2005, film studios gained a new revenue stream beyond the box office. VHS, DVDs and widespread home television sets enabled people to watch films in their homes. Following the box office release, this provided studios with another large chunk of revenue, enabling them to maximise the revenue per viewer (one viewer could buy theatre tickets and buy the DVD) and also the total audience size.

Now that DVDs and Blu-rays have largely disappeared, studios are faced with a double problem. Not only are there more films competing for the same box office revenue, secondary revenue streams are harder to come by, relying on hard-to-copy advantages like Disney’s theme parks or low-return options like streaming services.

These financial forces create a lot of pressure to maximise box office sales. Studios will usually take between 50-60% of the total revenue, with the rest going to the theatre. Even in the best case, breaking even on a $200M film investment means returning ~$340M at the box office. There are not that many films each year that hit this figure.

Why does this matter? Well, studios must make strategic bets on the films that they believe are most likely to sell lots of tickets at the box office. Over the past 25 years, that has led to a significant shift in priorities.

Studios stick to proven formulas to maximise ticket sales

To illustrate the change in priorities, we can look at how the top grossing films each year have changed over time. Here are the top ten grossing films in the past five years, comparing the the number of sequels (blue) with new/first film IP (red).

80% are sequels.

Here are the top ten grossing films in the five years up to and including 1999.

Only 14% are sequels.

Seen another way, box office revenues through the 2000s gradually centralised around major IP franchises.

The pattern here is very clear. In the 1990s, studios made money by creating or converting new IP. In the 2020s, studios make money by pumping out sequels.

The driving reason behind this pattern is that it is less risky to bet on existing IP than it is to create new IP. Existing IP franchises have already done the hard work of building a world that fans love. In turn, fan loyalty provides studios with more certainty that their investments will pay off. When taking a $200M risk with declining theatre sales and no (significant) secondary revenue stream, studios are more inclined to take the offer.

Box office revenues centralise around a few large studios

In these financial conditions, large studios have a significant advantage. With better access to capital, large studios can distribute the risk across several large bets per year. At this level, a single smash-hit film can put a studio into profit, returning all capital invested across all films produced that year and then some.

For the big studios, a good year looks something like this — below is the 2023 roster for Universal Pictures. Notice that more than 50% of the revenue, but more importantly, almost 80% of the profit is coming from one film. Even though Universal invested more than half a billion dollars into Fast X and made a very meagre return, it was irrelevant because The Super Smash Bros. Movie was a super smash hit.

Only the largest players can afford to run this playbook. It takes a lot of capital and excellent distribution advantages to pull this off, and it is hard for smaller studios with innovative ideas to compete.

This is not to say that there are not other successful players. A24 is a great example of a production company making world-class films, usually original stories, on massively reduced budgets. But they are an exception to the rule.

Can a new generation of startups disrupt the Hollywood monopoly?

Hollywood has hit the peak of a cycle of maturity. Like all industries that hit this peak, it has become a steady state with a few companies that won big and languish as they enjoy their monopolies. In turn, we have seen a consolidation of box office revenue around major IP franchises and a reduction in the volume of original stories and innovative IP.

Emerging video models and realtime game engines disrupt the financial model, making world-class filmmaking accessible to small studios with much smaller budgets. At $0.5-1M for a feature film, a startup team on a typical silicon valley seed round can make multiple films before needing to raise additional capital. Importantly, they can do so at startup speed — days, weeks and months, not years.

Startups have an additional advantage in the ability to diversify their business model into emerging media forms, like AI agents. A small market today makes emerging media beyond the circle of concern for major studios, but significant for a startup – especially given that it is likely to grow in the coming years as part of a new era of storytelling.

I am optimistic that this will lead to an explosion of startup studios willing to take creative risks again, and create a new arena of competition against the Hollywood monopolies. Through it, my great hope is that we have a chance of moving away from the sloppy blockbuster franchise model that has come to define the last decade of film.