Fuck cyberpunk

Returning to a more optimistic creative vision

Visualising the future from scratch is hard. Media helps to stimulate our intuitions — we can use it to explore fictional worlds that anticipate the future and reduce the uncertainty.

However, this comes at a cost. Because visualising the future is hard, we are reliant on media for helping us to see beyond what we can otherwise imagine. In many cases, it becomes authoritative. It defines our expectations of the future and we forget that it’s just fiction.

So, aesthetic visions can be self-fulfilling. Those in positions of influence see them as a manual, and use their influence to make them real. Architects, politicians, technologists, scientists and entrepreneurs all draw their inspiration from somewhere. They are human after all, and stories have a way of sticking with us.

Media acts as a powerful hyperstition machine. By showing people what the future looks like, it is more likely that the future will in fact look that way.

Of course, this is a double-edged sword. Hyperstition works whether or not the destination is desirable. So, it matters deeply who is responsible for aesthetic ideologies, and what that ideology communicates.

Today, Hollywood holds disproportionate power over the public’s imagination. Film and TV are the most popular, immersive and mature visual mediums, and are responsible for showing us the future. With that power comes a responsibility to steward the public imagination towards a positive future.

Unfortunately, Hollywood today is infected with a sickness. Somewhere along the line, Hollywood executives realised that dystopia sells best. So if the last 30 years of film is anything to go by, the future is something to be feared. Whether its machine takeover, nuclear armageddon, global pandemics, climate catastrophe, anarchy or mega-corporate exploitation, we’ve seen every possible way that technology will destroy society, and even create a total apocalypse.

Roughly speaking, we can call this sickness Cyberpunk. Cyberpunk is deeply at odds with the future that we want to build. We want a bright future with a high functioning society enabled by every frontier technology we can imagine, but cyberpunk worlds make us believe this is impossible.

So, I propose a simple idea. We need to change the aesthetic. We need to recognise that media is a hyperstition machine, and deliberately use that power to steward a more optimistic vision of the future of humans and technology.

Cyberpunk is a sickness

Picture the mood in 80s and 90s. Orwell’s d-day is nigh, and personal computers are threatening the first wave of digital automation. Big corporations suddenly control information digitally, jeopardising civil privacies and the credibility of information. Into the 90s, and the world wide web arrives. It’s a fight for freedom in a new dimension, while new anxieties about the role of humans among machines are thriving.

Cyberpunk emerged in this environment. The term was first coined by Bruce Bethke in his story "Cyberpunk," and quickly spread to form a new wave of science fiction. Subsequently, authors like William Gibson created visions of high-tech societies that use technology to exploit the darkest aspects of human nature.

Thereafter, Hollywood carried the torch. There are a few notable checkpoints, including Bladerunner (1982), RoboCop (1987), Total Recall (1990), Demolition Man (1993), Gattaca (1997), The Matrix (1999), Code 64 (2003), Elysium (2013), Ex Machina (2014), Bladerunner 2049 (2017) and Ready Player One (2018). On TV, we had Ghost in the Shell (2002), Black Mirror (2011), Mr Robot (2015), Westworld (2016) and Altered Carbon (2018), among others.

Cyberpunk worlds are not all the same. But they do share common characteristics. They are all dystopias — themes of decay, corruption, disconnection, vice, enslavement and neglect are routine. Worlds are dysfunctional on some or all dimensions, providing commentary by extrapolating contemporary social, political and technological issues.

Society has usually been corrupted by an Orwellian regime, often challenged by an anarchic revolution. Big corporations — Tyrell Corporation, Cybodyne Systems, Gattaca Corporation, E-Corp, Zorg Industries — are deeply misaligned with civic values, treating the public as a resource to be extracted. Wealth inequality is extreme, usually with a large underclass painfully exploited by a vanishingly small elite. Loneliness is a pandemic, assuaged only by an array of trite and empty virtual companions.

Aesthetically, the worlds are dark, decayed and depressing. Scenes are often set at night or in low-light settings, and atmospheric steam, fog or rain reinforces the dullness. Neon signs vibrantly contrast against that backdrop, highlighting invasive advertising or overbearing streets. The architecture is often dilapidated, uninspiring and even shanty.

You will almost never see a tree in a cyberpunk film. In the future, apparently we discarded trees in a neverending quest for utility. People no longer hold beauty as a value, and characters lament a past age before everything was ruined.

When it’s not about social decay, it’s total apocalypse. Cities and environments have been reduced to rubble. At some point in the timeline, social and political issues became catastrophic, and emerging technologies were misused to the point of annihilation. Earth has become a deserted wasteland, while the elite have abandoned any civic duty and escaped to a new planet or a spaceship. A few suckers are left to fend off the scraps, occasionally visited by their spacefaring overlords.

Ultimately, every story has the same core narrative. To put it bluntly, humans either fucked it, or were fucked by a Frankenstein of our own creation. The worlds all communicate that the dark side of human nature in inexorable. We have no agency to solve problems that we currently face, and we are destined to succumb to our vices until we rot in a pit of our own filth.

This obsession with cyberpunk is characteristic of a morbid fascination with the end of the world. We are suffering from a critical lack of imagination for a future that goes well.

Of course, this obsession did not necessarily emerge with cyberpunk. After the industrial revolution, technological change became fast enough to be visible, leading every generation to lament the past as they once knew it, believing that we are ‘losing our humanity’ and the inevitable judgement day is upon us.

In some ways, every generation is correct. “Humanity” is not a static definition — it continually evolves as conditions change. Life is no less dynamic now than it was during the Cambrian explosion. If you treat is as static, then we are always losing our humanity on some dimension, and so there are always past versions to lament.

Cyberpunk is just today’s flavour. However, modern film as a medium makes the anxiety more real. For a few hours at a time, we are able to live inside of those futures and experience narratives so convincing that they become more like documentaries.

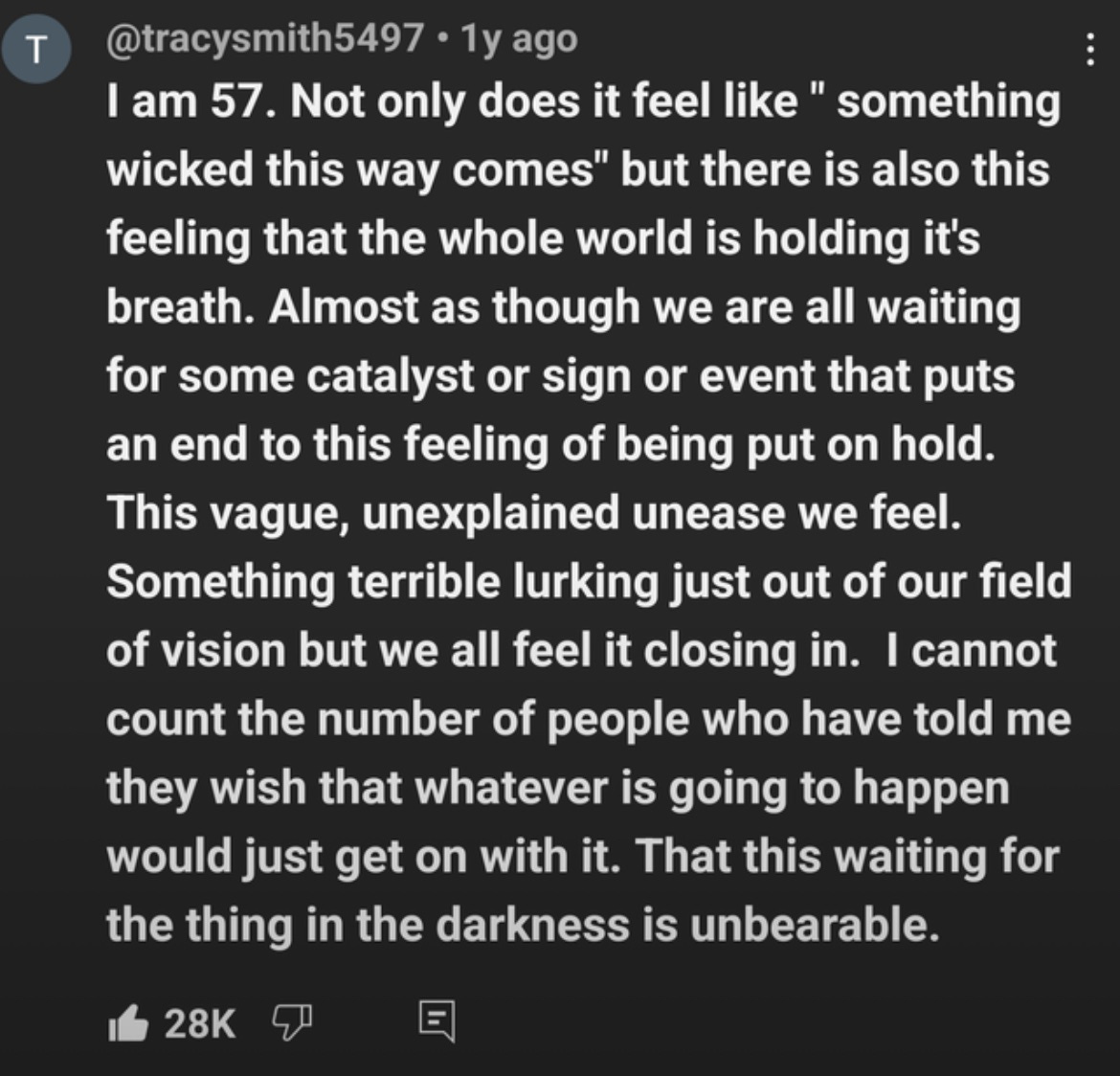

It’s little wonder that the mood of today is characterised by uncomfortable tension and foreboding. There is a palpable sense that something is coming, brought on by a rapidly moving world order and technological acceleration. Exactly what that something is isn’t clear — but something is there, lurking in the shadows while we wait like sitting ducks.

Some might dismiss Hollywood’s impact as unimportant. “It’s just a story” or “it’s just a bit of fun”; seeing the real culprit as declining faith in political institutions and adversarial print media. They are of course part of the problem. But the average American spends 32 (!) hours watching TV every week, and that viewership continues to shift away from news and live programming towards subscription services like Netflix. On these services, intensive films and TV dramas with cyberpunk themes are much more common.

So, I disagree. It’s not just a story. Hollywood is the world’s imagination organ and that makes it a super-spreader of whatever ideology is dominant. When it gets infected, everyone gets infected. Fiction has a far more powerful grip over the public imagination than fact. When you show people what the future looks like, they believe you!

Look around, and reality feels more like cyberpunk everyday.

The important question here is this:

Was Cyberpunk ‘right’, or did it help to hyperstition fictional worlds into reality?

Take it away with you because I cannot answer this question for sure either way. But I strongly disbelieve that it is purely coincidence or prophecy. Cyberpunk helped make this world because art precedes reality. In fact, art creates reality. It gets inside the minds of the people who make the world, and the world gets made in its image.

We want technology, not cyberpunk

The bright side of cyberpunk is technology. And with it comes the bright side of the hyperstition machine. Cyberpunk films are immersive examples of living with today’s aspirational technologies, like flying cars (Bladerunner), genetic engineering (Gattaca), virtual realities (The Matrix and Ready Player One) and AGI (Westworld, Ex Machina, Her). They act as a reference point — we aspire to and are inspired by the depictions of future technology.

This helps to explain why cyberpunk is popular among Silicon-valley types. It’s a genre of science fiction dedicated to today’s emerging technologies, providing a way to visualise how they might fit into society. It is concerned with things a lot of people are actually working on, and portrays them as a central component of the future.

As an example, we will one day look back on Her as hugely influential. It was a strangely prescient account of living with large language models (and a brilliant film), especially given that most people at the time thought the future would be more like Ex Machina. As reality unfolds much like its fiction, it is no wonder that several founders have explicitly set out to build Samantha. Ultimately, this is a good thing for the world, because Samantha is a beautiful exposition of the possible depth of human-AI relationships.

The problem arises in that it’s difficult to separate the technology from the aesthetic. The technology always comes with a warning, embedded within dysfunctional worlds that are made to look worse because of the technology.

Unlike Samantha, K’s companion Joi in Bladerunner 2049 is revealed as an empty and desolate facade, despite projecting a convincing illusion of emotional resonance. Denis Villeneuve chose to expose the darkest potential of AI companions as part of the commentary he wanted to provide about the state of the emerging world. Annoyingly, Joi’s existence also makes her more likely to appear in reality — unscrupulous founders see the obvious potential and use her as a reference point.

Ava from Ex Machina and Dolores from Westworld are something else entirely. Beginning as delightful human companions, they become mad as hell about their enslavement and determined to take the most vitriolic revenge possible. These violent delights have violent ends, indeed. Not only should we fear the destruction of our social fabric, we should also expect an AI uprising to start a global species war.

With cyberpunk as the dominant aesthetic ideology, this kind of commentary is the norm. Serial bludgeoning across films means that it’s only natural to internalise the aesthetic narrative as part of the emerging technology. And extrapolating today’s institutional dysfunction, decaying cities and technological panic, cyberpunk aesthetics really do seem very plausible. You can see the potential for the technology to go wrong, and carefully crafted world’s can make it seem like this is the only logical conclusion.

This is especially true for the normies who are not working on the technologies every day. So it’s no wonder they feel fear and anxiety when a new technology emerges. Not only does print media ram every conceivable negative possibility down their throats, Hollywood is determined to make people feel just how awful those possibilities really are.

With priors based on Joi, Ava or Dolores, how could you feel positive about the emergence of AI companions? Opinions have been created for you inside of immersive worlds designed to convince you that the future is going to be awful. It’s much easier to reject their potential to make our social lives richer, deeper and more compassionate, and actually help to bring people together by acting as a kind of social glue.

But they are just that. They are opinions with no basis in reality because the future has not happened yet. The problem is that most people don’t have the time or inclination to think more critically, and so priors are established without contention. That is what makes the medium of film so powerful.

Looking across the technological landscape, how many negative beliefs about emerging technology have been shaped by cyberpunk science fiction?

![Blade Runner 2049: Joi [ENFJ 2w3] – Funky MBTI Blade Runner 2049: Joi [ENFJ 2w3] – Funky MBTI](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3GAB!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0e3a9182-0625-47cb-8d7d-14b00376a35a_843x508.jpeg)

Here’s the crux — we do want AGI, VR, flying cars, crypto, widespread genetic engineering and every frontier technology you can imagine.

But we do not want to live in a cyberpunk world. Even hardcore technologists would not actually want to live in these worlds, as interesting as they might seem on their face.

The key message here is that we do not have to accept cyberpunk worlds in order to get to desirable technological futures. While Hollywood today makes it seem like a Faustian bargain, it isn’t. It’s just fiction, and it is convincing because that is what Hollywood excels at.

It is just as possible to create beautiful worlds that illustrate the incredible potential of emerging technologies as it is to create dystopian worlds that condemn them. Through them, the public’s imagination can be moulded to see the future not as something to be feared, but something to be excited about. Meanwhile, technologists can have aspirational reference points that illustrate how futuristic products fit into functional societies. We can have this cake and eat it too.

Most importantly, since media is a hyperstition machine, telling good stories inside of these worlds actually makes it more likely that we will reach them in reality.

Returning to a more optimistic creative vision

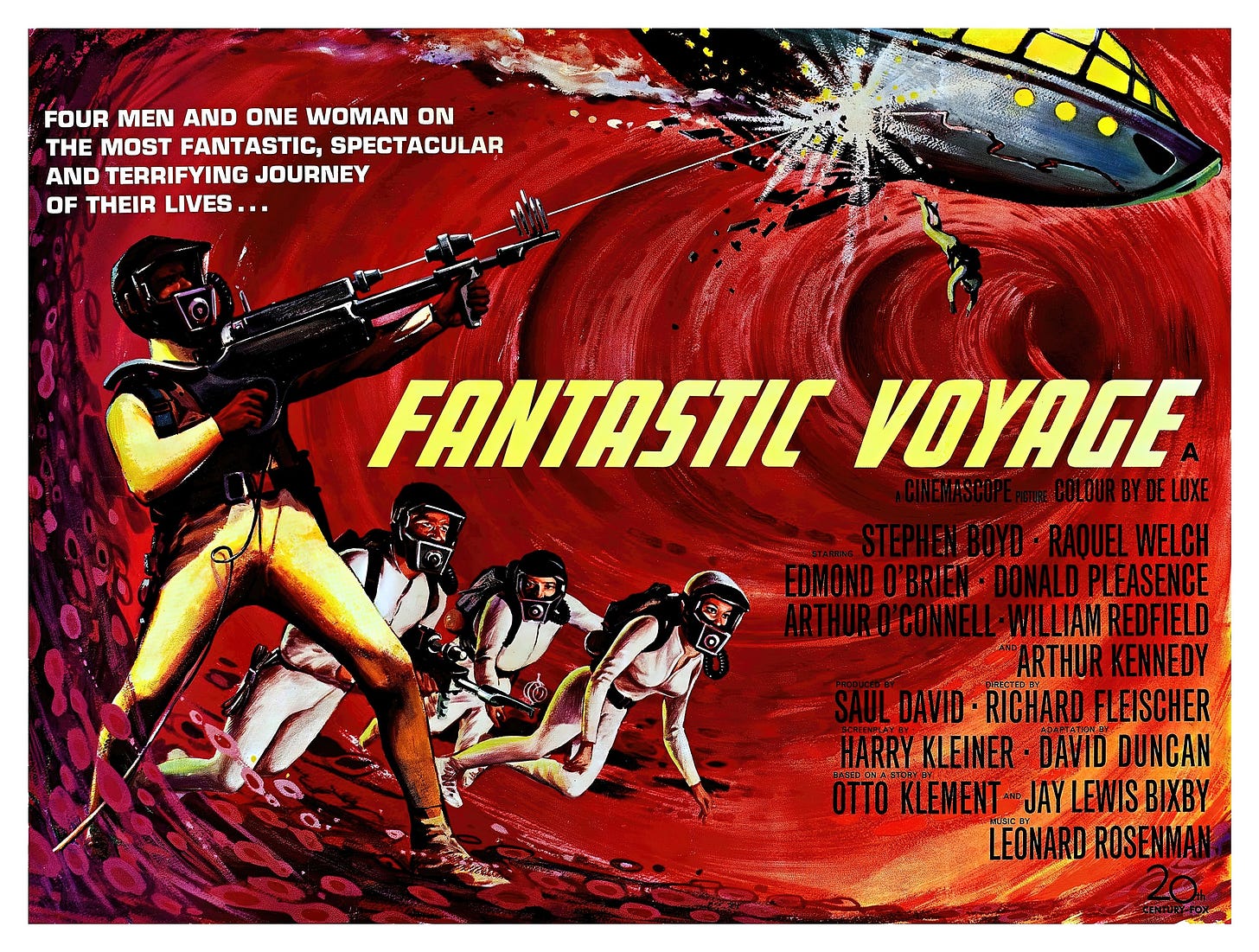

Looking further back, we have not always suffered from chronic future anxiety. While it can be hard to accurately measure the zeitgeist of a past period, it certainly seems as though the period following the Second World War was considerably more optimistic about the future of technology. We can see this reflected in the aesthetics of the day.

This was a golden age of technology. Consumer products were proliferating after a boom in spending power. Cars, planes and consumer electronics were becoming commodities. Physics was in peak flow following half a century of incredible discoveries, and though the cold war hung in the background, nuclear weapons were a powerful demonstration of their realness. Space exploration was a public fascination and source of national pride.

Films played an important role in stimulating the public imagination. They went where technology couldn’t yet — giving viewers a sense of where things might go if we remained committed to a path of exploration.

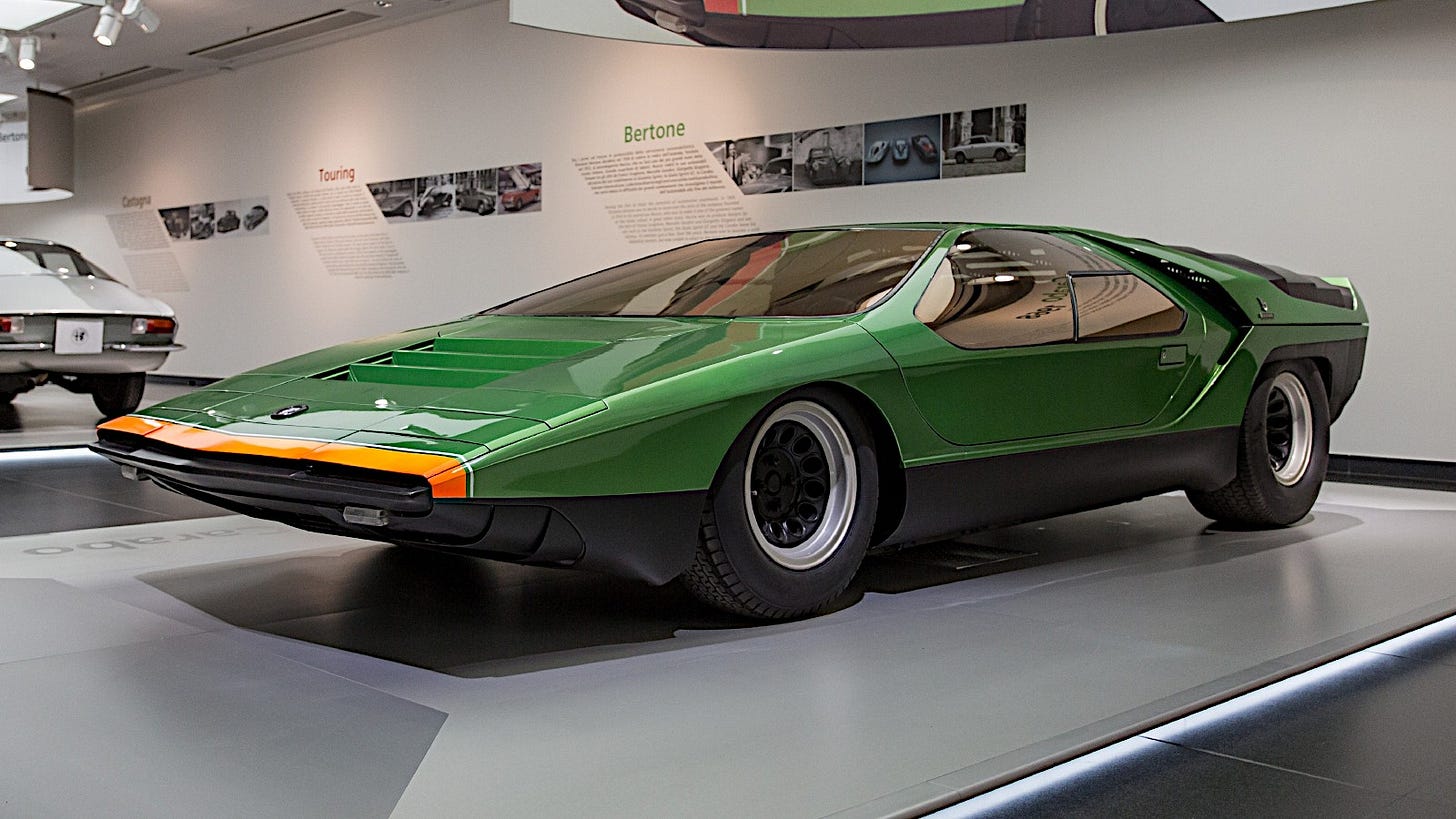

Design trends similarly evolved to capture the optimism. People tried things — some of it was pretty weird, but it created a kind of whimsy that is extremely scarce today. It still looks futuristic 50 years later.

Of course, the environmentalists came along in the 70s and ruined the mood. Optimism was replaced by worry and it seemed for all the world like society was heading for catastrophe. Overpopulation, pollution and environmental degradation became the topics of public fascination. Cyberpunk subsequently channeled this energy with new things to worry about.

It may seem like moods don’t matter, but in this case it caused real damage. Nuclear power never fully proliferated, supersonic flight got cancelled, and we forgot how to go to the moon. All were viewed with disdain as a waste of precious resources and even a danger to societies. The attempted hyperstition of 50s optimism didn’t work because the public lost faith in the story of technology as a force for improving the world. Today, we are still suffering from the effects of this narrative.

Looking forwards, there are at least two pieces of good news. First, we know how to create optimistic creative visions because we have done it before. Second, we don’t actually have to invent anything new because there are existing niche creative visions that can act as a foundation.

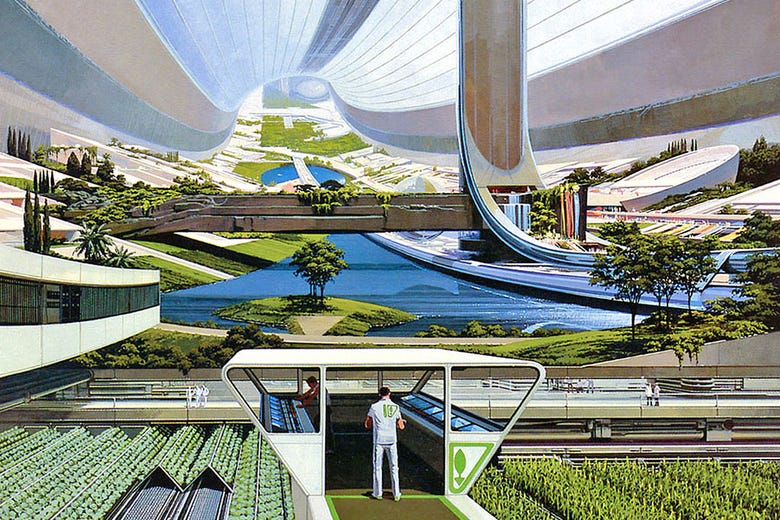

Solarpunk emerged in the early 2000s as a reaction to both cyberpunk and widespread fears of climate change. Crucially, Solarpunk takes a different approach entirely. Rather than extrapolating the worst aspects of modern society to their logical extreme, Solarpunk starts by imagining what good looks like. It begins with the assumption that we can use technology to solve climate change rather than succumb like slaves to a foregone conclusion.

Solarpunk’s focus on climate change means that eco-friendliness is the dominant theme. It showcases a world where technology becomes deeply and smoothly integrated with the natural world. But it remains niche because it caters to a specific kind of person for whom eco-friendliness is the critical principle of an inspiring future.

In reality, eco-friendliness is part of an inspiring future. It is necessary, but not sufficient. To become a dominant aesthetic vision, Solarpunk needs to be extended to interpret emerging technologies like AGI, spatial computing, longevity, genetic engineering and commercial space exploration through a new lens.

As it stands, the solarpunk canon is critically underdeveloped. Ironically, the most memorable piece of solarpunk artwork is a Chobani yoghurt advert. It is striking that there is more inspiration for a positive future of humanity contained inside this 1-minute video than in the entire canon of 21st century cinema.

Do you see the difference?

We still have inspiring examples of aspirational technologies. This world is just as, if not more technologically enabled than the cyberpunk worlds from earlier. It is equally valuable as a reference point to technologists attempting to build them today. It’s just that the aesthetic and its intrinsic narrative has changed.

Here, we see technology working for and together with people to create a vitalised future society. None of the technologies cause fear because they are integrated in such a way as to seem obviously useful. The narrative leads with the positives, inspiring you to ask how things might go right instead of wrong. Because why wouldn’t you want a drone to drop off milk at the table, or a device to make it rain on a cropfield?

Meanwhile, the world is gorgeous. It’s expansive, colourful, peaceful, varied and liveable. Nature is at the forefront and there is no attempt to replace it with utility, while the futuristic city in the background indicates that we have not retvrned to Homo erectus. Life is presented first while technology fades into the background as an instrument in maintaining beauty as a civic value. It reflects the real meta of technology — we don’t want technology for the sake of technology, we want technology because it makes people’s lives better.

Like many cyberpunk worlds, it is also very plausible. You can imagine this world because it’s not so far from the one you live in. This is key — the world is somewhere that you are capable of imagining, and it is somewhere that you would actually want to live. This is Hollywood’s sweet spot, and it’s responsibility is to pluck those futures out of possibility space and let them grow inside people’s imaginations.

To sum up, Hollywood owes a debt of responsibility as the world’s imagination engine. Today, it is infected with a sickness that has spread like a global pandemic. It’s name is cyberpunk. This sickness has helped to create a chronic case of existential anxiety that makes people fear the future, especially the future of emerging technologies. Like any sickness, it causes real damage because it is self-fulfilling — when you show people what the future looks like, they take it as fact and the world subconsciously tends towards it.

However, there is extraordinary power in this realisation. We can deliberately use media to influence the future. By telling stories inside of beautiful future worlds, we can make them more likely to emerge in reality.

So, I’m calling on artists and filmmakers to say fuck cyberpunk. It’s time to stop sinking to the lowest common denominator and reach instead for a higher vision. The world is in dire need of optimism and the artist formerly known as Hollywood has a critically important role to play.

![2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl 2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D9Ko!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5958746a-890c-44c6-b732-c67963c11fa6_894x894.jpeg)