Science fiction has a job to do

And its bigger than prediction

Science fiction can appear as a way to predict the future. Even great sci-fi writers often believed they were prophets predicting a future that was otherwise inevitable.

Trying to predict the future is a discouraging and hazardous occupation, because the prophet invariably falls between two stools. If his predictions sound at all reasonable, you can be quite sure that in 20, or at most 50 years, the progress of science and technology has made him seem ridiculously conservative. On the other hand, if by some miracle a prophet could describe the future exactly as it is going to take place, his predictions would sound so absurd, so farfetched, that everybody would laugh him to scorn. — Arthur C. Clarke

When science fiction writers turn out to be correct, we laud them for their foresight. Seeing into the future is notoriously hard and something to be avoided by mere mortals. How could they have seen what everyone else could not?

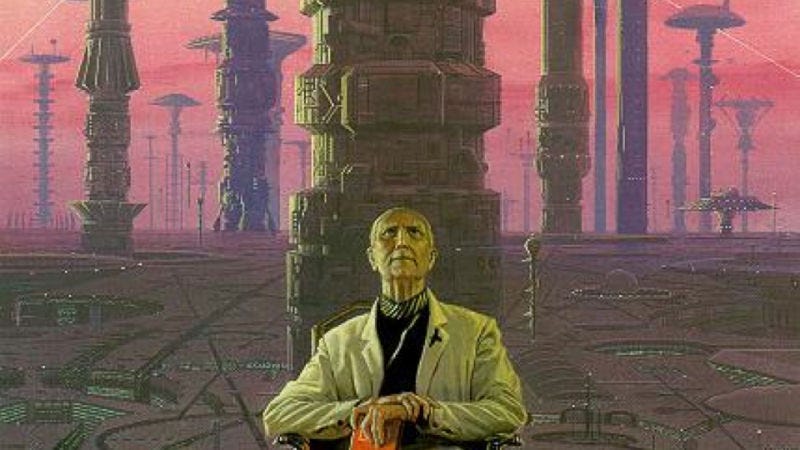

The idea of writer as prophet is best epitomised by Hari Seldon. In Asimov’s Foundation series, Seldon uses psychohistory to make predictions about the future. Through it, he foresees the fall of the Galactic Empire and a subsequent dark age. But since psychohistory only predicts in broad strokes, action can influence the course of the future. So, in an effort to reduce the length of the dark age, he sets up the Foundation — a group of people tasked with recording all human knowledge in order to guide the development of the new empire.

The core idea of psychohistory is that through a rational process, the future can be known in detail. And through that detail, you can identify points of leverage in the present that will affect the eventual outcome.

This is fiction when taken literally. Past a certain point, rational prediction is the wrong tool because the future is too uncertain. But it hints at something real which Asimov himself understood. You can see into the future, and you can use use it to identify points of leverage that change the eventual outcome. It just comes via a different mechanism. What looks like prediction on the surface is something else entirely.

You don't need to predict the future. Just choose a future — a good future, a useful future — and make the kind of prediction that will alter human emotions and reactions in such a way that the future you predicted will be brought about. — Isaac Asimov

Science fiction creates the future by inspiring people to take action when the technology finally arrives. Compelling stories become self-fulfilling prophecies because they guide actions in places where the facts haven’t caught up yet. This is the true spirit of psychohistory — you can tell stories about the future that end up coming true.

This concept has a name. It’s called hyperstition, and hyperstition is the real job of science fiction. It is a way to imagine a shared vision for the future before it is technically possible, and organise people across time and space to manifest that vision into the physical world.

Superstitions are merely false beliefs, but hyperstitions – by their very existence as ideas – function causally to bring about their own reality. — Nick Land

The lesson of hyperstition is that you can causally interfere with the direction of the future by telling compelling stories. Recognising this lesson is important because it allows us to be more deliberate. We have power over the future because we can use science fiction to deliberately influence long-term outcomes.

Great people are always inspired by something

Looking at great scientists and entrepreneurs, it is remarkable how many of them were originally inspired by fiction. In some cases, the effect is so strong that they are directly building versions of something that was first described to them in a story.

Elon Musk is perhaps the best example. He is well known for citing the canon of 20th century science fiction especially as it relates to the origins of SpaceX. He is particularly fond of Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Foundation and The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

However, the relationship between fiction and space exploration is much older than Elon. For some time now, something about space has felt like our destiny. Of course humans end up going to other planets, because what else would an advanced civilisation do? It feels intuitive, beyond any need to rationalise.

Why do we have this intuition? Where did it come from? It certainly wasn’t always this way — people in the Middle Ages were not talking about interstellar civilisations. They didn’t even know what space was.

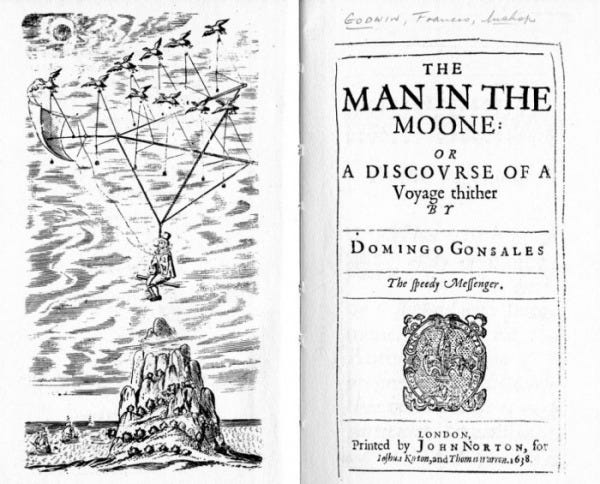

We can trace the idea of space travel at least back to the 17th Century. Wilkin’s Discovery of a World in the Moone (1638) and Godwin’s The Man in the Moone (1638) are early explorations. It probably sounded farfetched at the time, because there was no evidence to say that space travel was even possible. Galileo had only just discovered that the Earth orbited the Sun, and modern mathematics didn’t exist yet — Newton wouldn’t come along for another 50 years.

Clearly, 17th century society couldn’t to go to the moon. But that didn’t matter. What mattered is that fiction established an ambition to reach the moon. Within that ambition were two key ideas. First, the moon is a place that humans can go. Second, we are capable of building technology to make the journey.

So we can forgive Godwin for his geese-flying machine because the core ideas were enough to inspire the next generation. As it happened, that generation did not really arrive until the 1800s. Citing Godwin’s original work, Edgar Allen Poe published The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaall (1835), which described reaching the moon inside a hermetically sealed balloon.

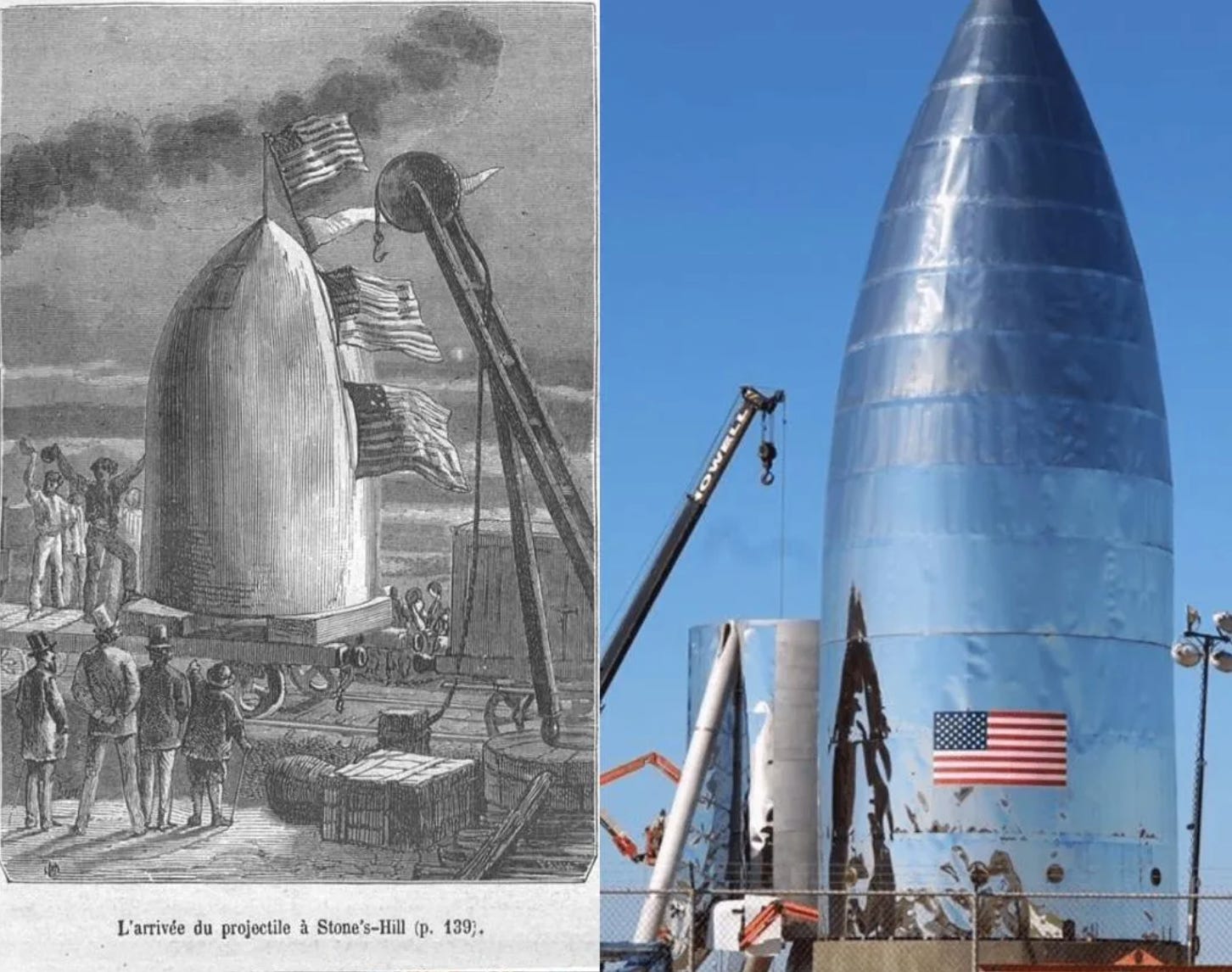

In turn, Poe inspired Jules Verne to write From the Earth to the Moon in 1865. Verne described firing humans at the moon from a giant space cannon. Rocket propulsion was still not understood, but we were getting closer to a workable mechanism. Notably, Verne attempted rough calculations about the requirements of such a cannon, and despite the lack of data available at the time, was remarkably accurate.

Verne’s novel inspired a young Robert Goddard. Fiction gave him the unshakeable belief that space travel was both possible and historically important. Through that belief, he was among the first to recognise that emerging technologies finally provided a way to make it real. He went on to become one of the founding fathers of modern rocketry, counting the multi-stage rocket (1914) and the liquid-fuel rocket (1914) among his 214 patents.

Goddard’s work laid the foundations for the space race. Thanks to his work and many others, we did go to the moon, realising a fictional dream that was now centuries old.

With the benefit of hindsight, we see that space travel was not an inevitable part of our destiny. The idea had to be created, and centuries of fiction shaped our intuitions into believing that it was inevitable. When the technology finally arrived in the 20th century, we didn’t have to use it to go to space. Rockets don’t just suddenly appear out of the components. We chose to build them, because the fictional vision of space travel was so inspiring that we felt compelled to make it a reality.

On the surface, it may look like fiction made a prediction. But Verne, Godwin, Poe and Wilkins did not predict the moon landings. Something else happened here that was much more important. Fiction created the cultural environment in which moon landings were able to happen, because it started a positive feedback loop over centuries that inspired generations of artists and technologists to turn fiction into fact.

Fiction hyperstitioned the moon landings into existence.

The space race of the 50s and 60s gave birth to a golden age of space-themed science fiction. Classic works like Foundation, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, Fahrenheit 451, The Martian Chronicles and Childhood’s End emerged in literature. Each painted ambitious visions of spacefaring civilisations spreading out across galaxies, enabled by advanced technologies far beyond our existing capabilities. Star Trek, Forbidden Planet and 2001: A Space Odyssey took the ideas and made them visual, stimulating a richer imagination than books alone could manage.

For years, it seemed like these visions were going to hyperstition us into an interstellar civilisation. Unfortunately, what actually happened is that human presence in space declined significantly and we forgot how to go to the moon. Space exploration took a hiatus as costs could no longer be justified.

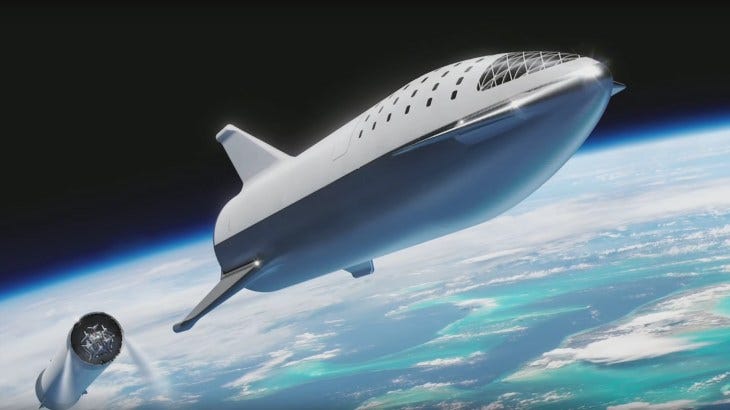

We can’t say how long this would have continued. What we can say is that Elon Musk took it upon himself to change it, and established SpaceX. Through the Falcon program and now Starship, SpaceX successfully revived a dying industry and made the dream of space exploration real once more. This time, it looks like we will settle humans on other planets. For good.

Elon credits Hitchiker’s Guide to the Galaxy for SpaceX’s core insight. That insight is that we currently do not know how to ask the right questions about the universe and our place in it, and our responsibility is to preserve the light of consciousness while we advance our understanding. Making life multiplanetary reduces the risk of extinction, and brings us closer to asking the right questions. Beyond that, it gives us something to believe in, and a reason to push through hardship in pursuit of something bigger.

…if you can properly phrase the question, then the answer is the easy part.

The universe is the answer, so what is the question? The more we can expand the scope and scale of consciousness, the better we can understand what questions to ask about the answer that is the universe. The more we can expand consciousness, and become a multi-planet species—ultimately a multi-stellar species—we have a chance of figuring out what the hell is going on. — Elon Musk

Like the moon landings, establishing a Martian colony is not inevitable and it never was. 20th century science fiction did not predict Martian colonies as our inevitable destiny. It established an ambition that inspired Elon to swear on all that is Holy to make it our destiny.

All great things happen because great people poured their life force into making them happen. That life force has to come from somewhere, and great people are always inspired by something. Elon is no different. Like Verne inspired Goddard to build the first rockets, 20th century science fiction inspired Elon to build Starship.

Fiction did not predict Starship. It helped to create it. And that is what makes it so powerful.

The effect of hyperstition goes beyond space travel. The metaverse is a similar example of a world-shaping reality emerging out of fiction.

It began with the concept of “cyberspace”, originally described in William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984). At the time, the personal computing revolution was only just beginning, and the world wide web wouldn’t come along for another 10 years. People needed a conceptual framework through which to understand what emerging technologies meant for society. Cyberspace provided that, inspiring the internet generation to shape the world in its image.

The metaverse extended cyberspace into a spatial dimension. It was first conceived by Neal Stephenson in Snow Crash, and built upon by Ernest Cline in Ready Player One. Through it, the internet became a place complete with three-dimensional environments, characters and a new economy.

The metaverse was a niche idea until it gained mainstream popularity a few years ago, following Mark Zuckerberg’s drastic reorientation of Facebook. Mark realised that owning the underlying platform was the source of Apple and Google’s dominance in mobile. He chose to reorient Facebook because it’s lack of ownership created a strategic vulnerability.

We are vulnerable on mobile to Google and Apple because they make major mobile platforms. We would like a stronger strategic position in the next wave of computing.— Mark Zuckerberg (2015 memo)

To plug this vulnerability, Mark searched for the next platform. He consulted science fiction for clues, and found the answer in Snow Crash and Ready Player One. He now specifically cites these works as major influences on his vision. As is now legendary, he even renamed the company “Meta” — a nod to Neal Stephenson’s original coinage.

Fiction inspired Mark to connect the dots with emerging technologies. Through Oculus, Palmer Luckey had shown that the technology for virtual reality was arriving. Mark reasoned that virtual reality was going to be the next platform, and Facebook needed to own it.

Our vision is that VR / AR will be the next major computing platform after mobile in about 10 years. It can be even more ubiquitous than mobile - especially once we reach AR - since you can always have it on. — Mark Zuckerberg (2015 memo)

Facebook’s best chance of owning this platform was to accelerate its evolution. So, Mark began investing huge amounts of money into Reality Labs and Oculus, Facebook’s respective research and product efforts. Today, Meta is spending >$10 billion every year to force virtual reality into existence. It has built the only VR platform that people actually use on a regular basis, and created the competitive drive that recently brought Apple to the table with Vision Pro.

…our goal is not only to win in VR / AR, but also to accelerate its arrival. This is part of my rationale for acquiring companies and increasing investment in them sooner rather than waiting until later to derisk them further. By accelerating this space, we are derisking our vulnerability on mobile. — Mark Zuckerberg (2015 memo)

Like it or not, Mark is disproportionately responsible for the emerging VR landscape. Whoever ends up winning, it is only a matter of time because Mark took it upon himself to force it.

So what happened here? Well, Mark believes Snow Crash simply predicted the future. He sees his role as accelerating a future that was going to happen anyway. His words are echoed by Sergey Brin.

I love science fiction. It’s often a good way to understand what’s possible… I’ve spent a lot of time reading the science fiction… It’s fascinating to me to see what people predict and what are the sociological phenomena that people predict around it. — Mark Zuckerberg (this interview)

[Snow Crash]… was really 10 years ahead of its time. It anticipated what was going to happen. — Sergey Brin (this interview)

However, like space travel, seeing the metaverse as a prediction is a misconception. Science fiction is fiction! It is only loosely grounded in reality, describing technologies and societies that don’t exist yet. It is not a definition of what is possible in any technical sense. It is about what is possible in the imagination before we have the technology to actualise it.

The metaverse was never an inevitable part of the future, and Neal Stephenson did not predict it. He created it, and in doing so, changed the course of the future because the story was so inspiring that Mark Zuckerberg felt compelled to make it real.

Looking forwards, there are no factual accounts of what the metaverse is going to look like. As Mark and others seek to make it real, inspiration has to come from somewhere. But the only information that exists exists inside of fictional worlds. So whether consciously or subconsciously, the industry will shape the metaverse to be as fiction first described it.

Snow Crash and Ready Player One are thus hyperstition tools — they will cause the worlds they described to appear in reality.

What should we take away from these examples? Well, here are two hypotheses:

Compelling stories become true because they inspire great people to make them true. 2020s space exploration would not have happened without Elon Musk, and the metaverse would either not happen or happen much later if not for Mark Zuckerberg. Neither would have happened if not for science fiction.

Stories create information in places where ‘facts’ don’t exist yet. In pursuit of making them real, people use them like a manual. When you show people what the future looks like, they believe you and shape the world in its image.

The critical insight here is that we have agency to forge the long-term future by writing compelling stories. Fiction might appear as a feat of prediction, but prediction falls short because it can’t inspire people to do what rationality says is impossible. You are much more likely to be correct by creating a story that is so inspiring that its very existence causes the future to make it a reality.

Science fiction has a job to do, and its bigger than prediction.

![2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl 2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D9Ko!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5958746a-890c-44c6-b732-c67963c11fa6_894x894.jpeg)