Tools create mediums

AI will be no different

In the 19th century, and for much of modern history, theatre (and live performance in general) was ‘the thing’ — the main storytelling medium. Traditionally, it had meant operas and classical dramas that were typically only available to the wealthier classes. But through the 1800s, it expanded into new performances like vaudeville and minstrel shows, which together with local venues, made theatre available to commoner people. While cost meant that it was never truly accessible, it retained a deep cultural importance as the height of social occasion.

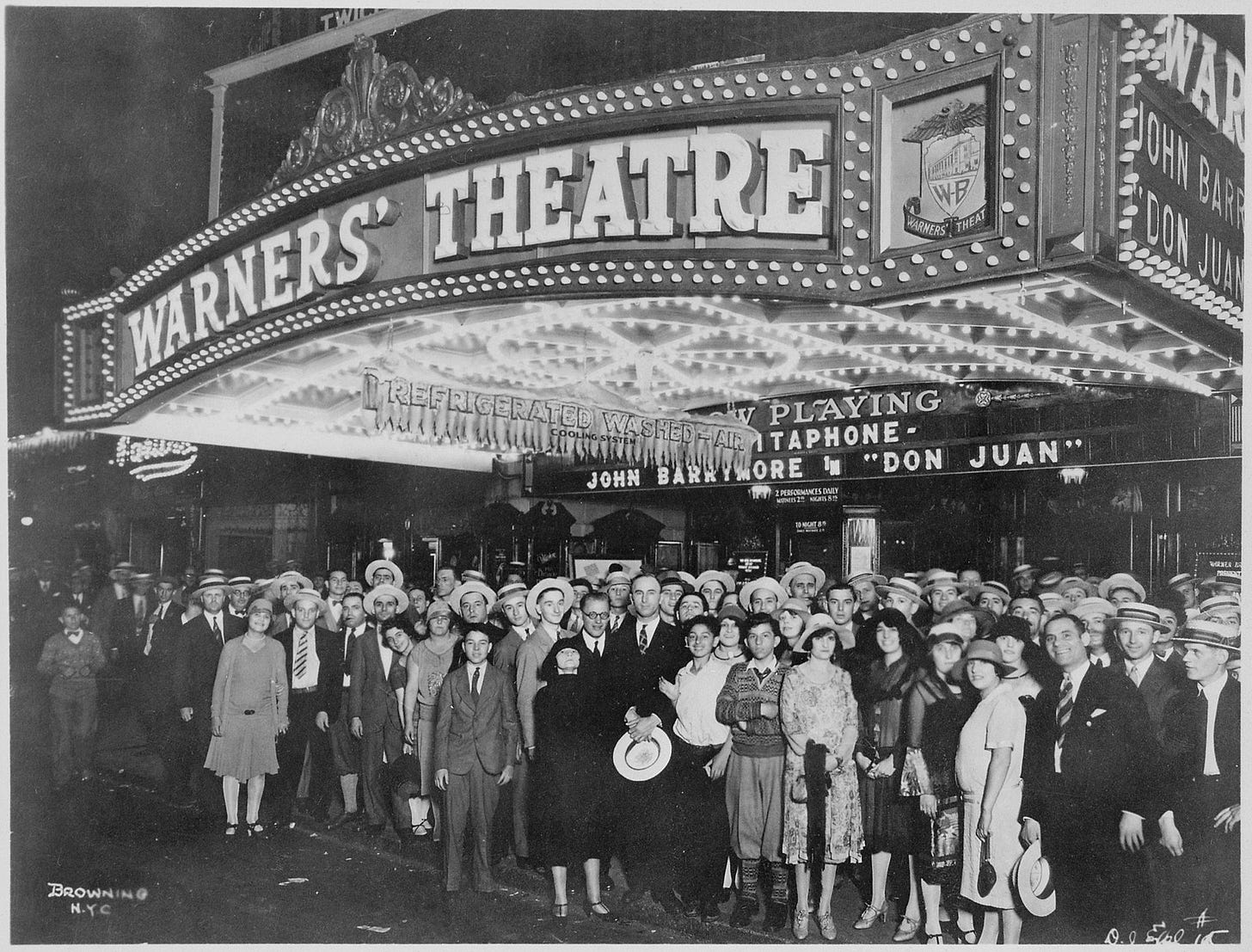

Broadway arose as the epicentre of American theatre, hosting the most prestigious events and new premieres. Improvements in transport, street lighting and public safety increased the potential patronage outside of New York, creating the conditions for a scenius to arise. The best talent and venues coalesced alongside the wealthiest patrons, and by the early 1900s, Broadway had matured into the kind of glamorous showbusiness that came to typify the Roaring Twenties.

Of course today, theatre is more niche. This is largely due to the emergence of film, beginning with Lumières’ first demonstration at the Grand Café in Paris in 1895.

Their invention, Le Cinematographe, was a camera and projector in one. It used a hand crank to push a roll of film through a lens mechanism, with each frame pausing momentarily to enable exposure. On playback, the same mechanism held frames against a light source to project it onto a surface. It was light and portable, making on-location filming simpler.

For those in the audience, it was the first time seeing moving images on a screen. So consider the alarm they felt when they saw an oncoming train hurtling towards them. "Et mon cul, c'est du poulet?", “Merde” and “Sacré bleu”, you might imagine. Of course, they soon realised there was no danger. The train was simply a projection, and they had in fact witnessed the birth of a new medium.

Ironically, the Lumière’s doubted the practical applications of their invention, causing Louis to declare film as “an invention without a future”. In actuality, they had created the first mass market entertainment medium with instant appeal to the public imagination.

Henry Ford once said “If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses”. Perhaps if you asked someone in the late 1890s what they wanted from film, they might have said a way to record theatre shows.

Early film pioneers, thankfully, understood that the new medium meant new creative possibilities that the stage could not capture. Films could be created on location. Special effects could fool the audience. Time and space could be manipulated with ease. With it came new business opportunities — scenes could be shot a single time and watched infinitely, while actors didn’t need payment for repeated performances.

Even the earliest films used these advantages to explore new directions. The Lumières first premiered a series of silent documentaries. Early film studios created the likes of The Great Train Robbery (1903) and A Trip to the Moon (1902) — one of the earliest science fiction films.

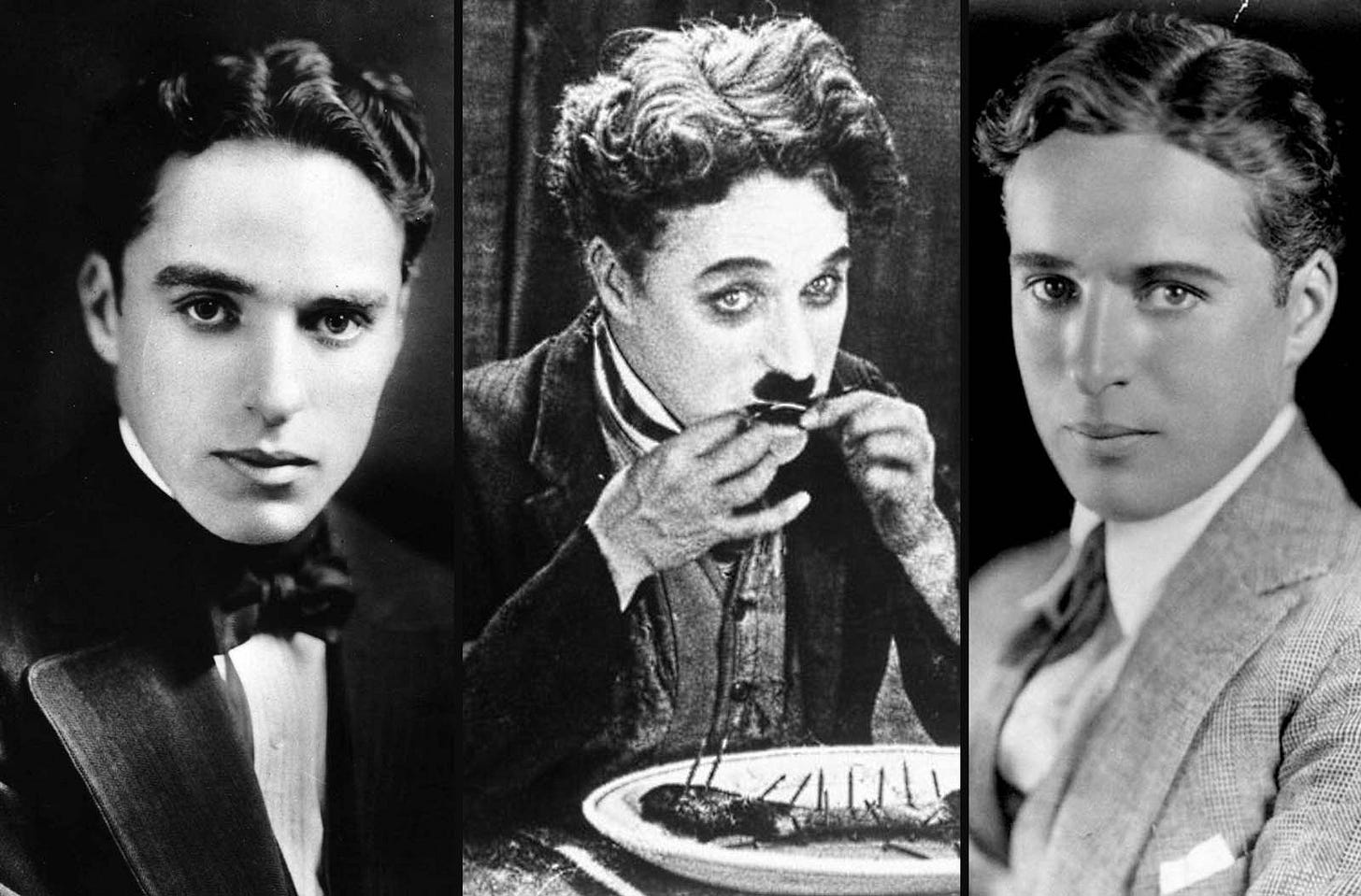

Still, as an art form, film was closest to theatre. New York remained its epicentre, and after the Lumières’ demonstration, most of the emerging film talent arose out of the Broadway scene. Theatre performers were excited by the new medium and the possibilities it opened up. One of them was a young Charlie Chaplin.

Chaplin had grown up in Victorian Britain. Both parents had been music hall performers — a mix of comedic, musical, and variety acts known for lively audience participation and social commentary. Chaplin showed ambition for a life in showbusiness from an early age, performing in music halls from as early as 10 years old. At just 16, he moved to America and became a fixture of the vaudeville circuit, calling New York home.

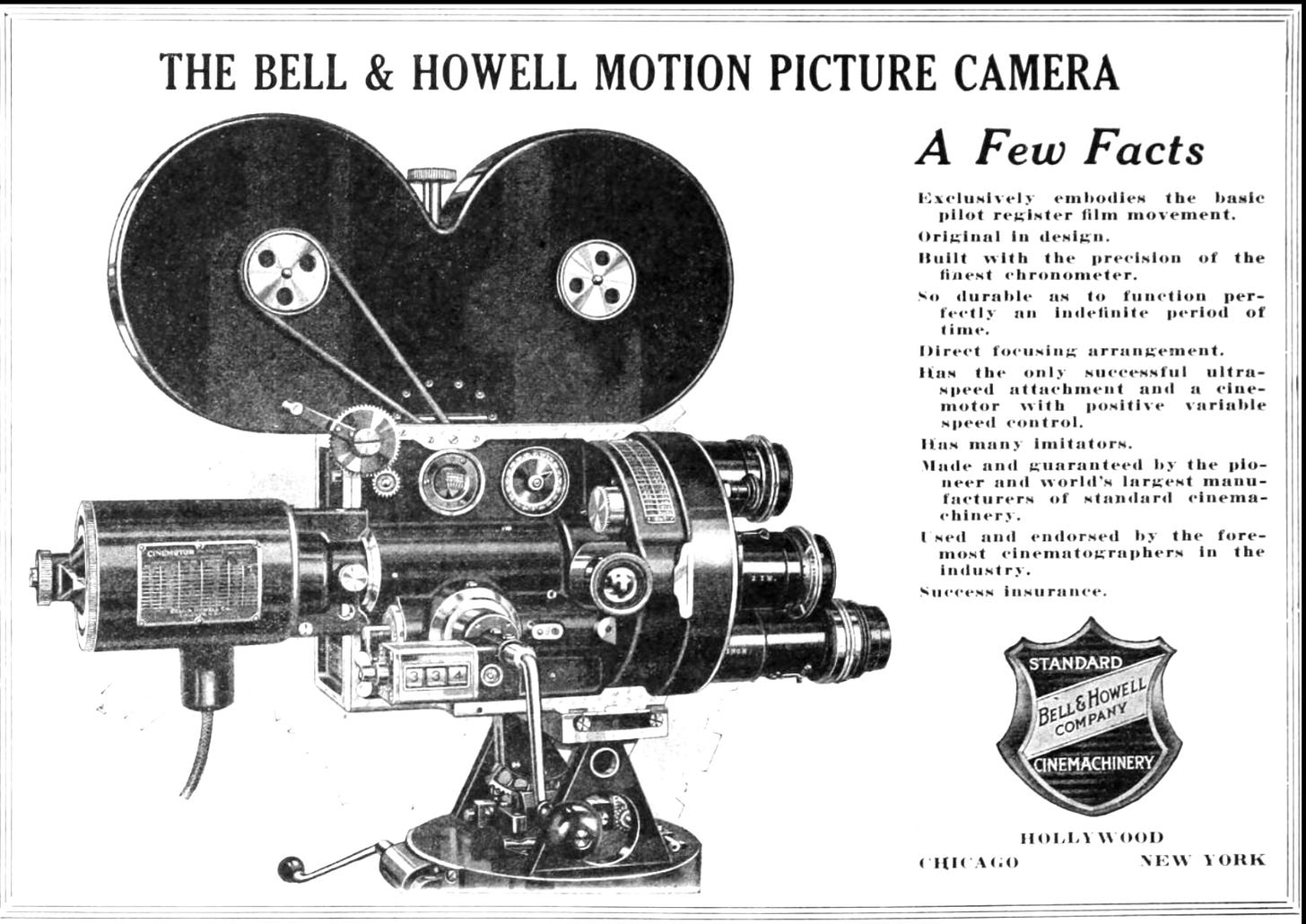

Around the same time as the Lumières, Thomas Edison had created a competing camera product, the Kinetograph; one of the first commercially available film cameras. He had also founded Edison Studios, one of the first production studios.

Sensing an opportunity to monopolise the budding industry, Edison patented his technology and established the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPCC) together with the nine major film studios at the time.The MPCC sought to use fees to control who could legally produce, distribute and exhibit films. Without a mature market of options, filmmakers were forced to comply with MPCC’s terms or risk legal action.

By the 1910s, Chaplin was one of many filmmakers who migrated West to Southern California to escape the MPCC’s patents. They were largely only enforceable in the East, and new cameras like the Bell & Howell 2709 provided competing options. Besides, good weather provided the ideal environment for filmmaking.

Many of today’s major film studios got their start in this era, with MGM, Paramount and Universal key fixtures of the growing renegade movement. Much like Broadway had done for theatre, Hollywood did for film — money, talent and facilities increasingly cemented it as the home of global cinema.

In the early years, actors’ names had not been associated with films, with all credit given to the director. After working with a series of studios, Chaplin became one of the film industry’s first auteurs and moviestars after his breakout role in the The Tramp (1915). Just a year later, he became one of the highest paid people in the world, signing a contract with Mutual Film Corporation worth $670,000 per year (~$20 million in 2024). Thereafter, ‘stardom’ became systematised, and showbusiness as we know it today began to evolve.

[this fellow is]… a tramp, a gentleman, a poet, a dreamer, a lonely fellow, always hopeful of romance and adventure. — Charlie Chaplin

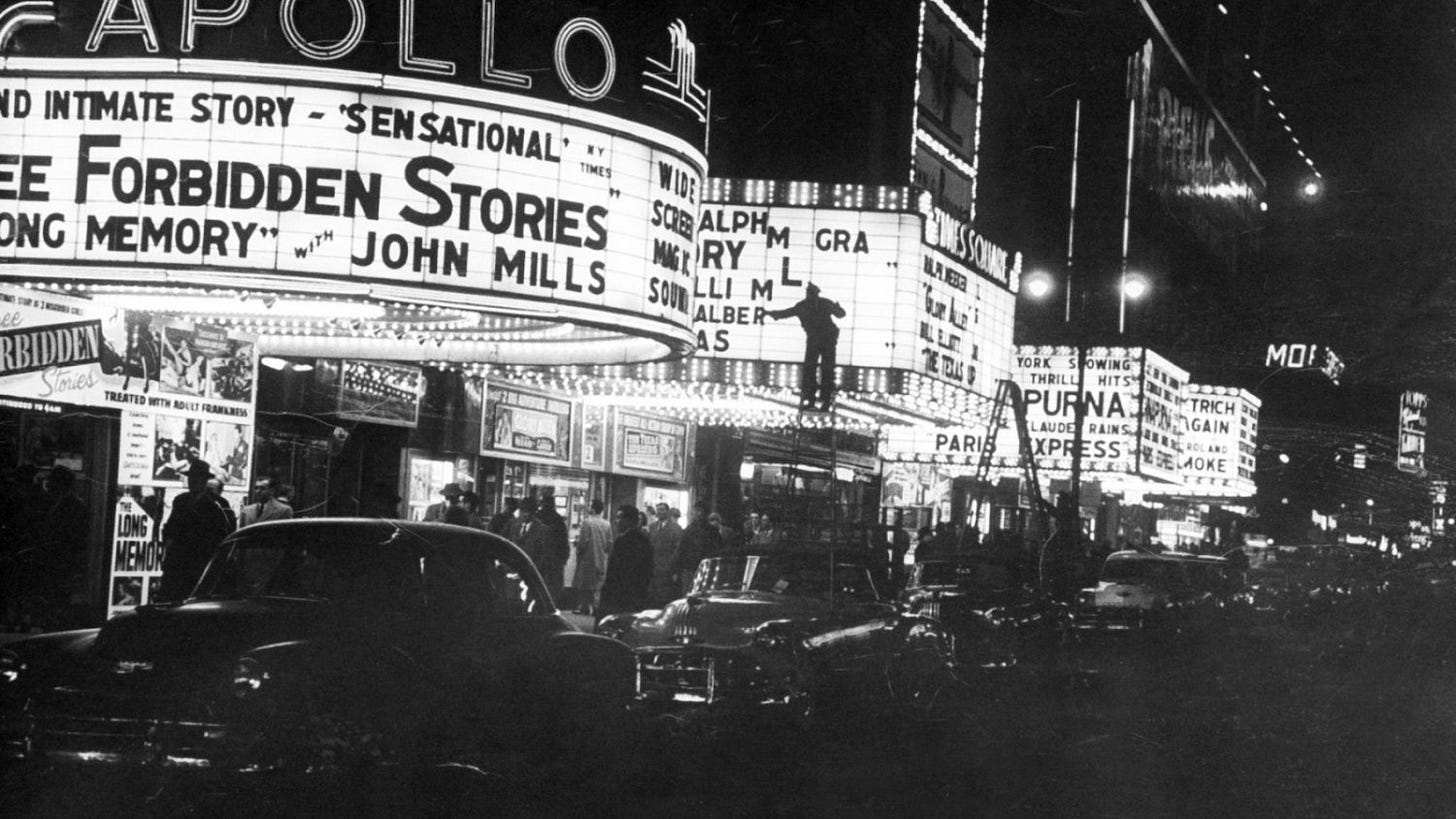

Chaplin’s rise fueled cinema’s rise into the Roaring Twenties. Silent films were maturing as a medium, and Hollywood was emerging as its centre. By the end of the decade, films acquired synchronised sound with the release of The Jazz Singer among other titles. Sound enabled the mainstream breakthrough, and despite the challenging economic environment, created a golden age of cinema through the 1930s. Classics like Scarface (1932), King Kong (1933), Gone with the Wind (1939) and the Wizard of Oz (1939) all emerged from this era.

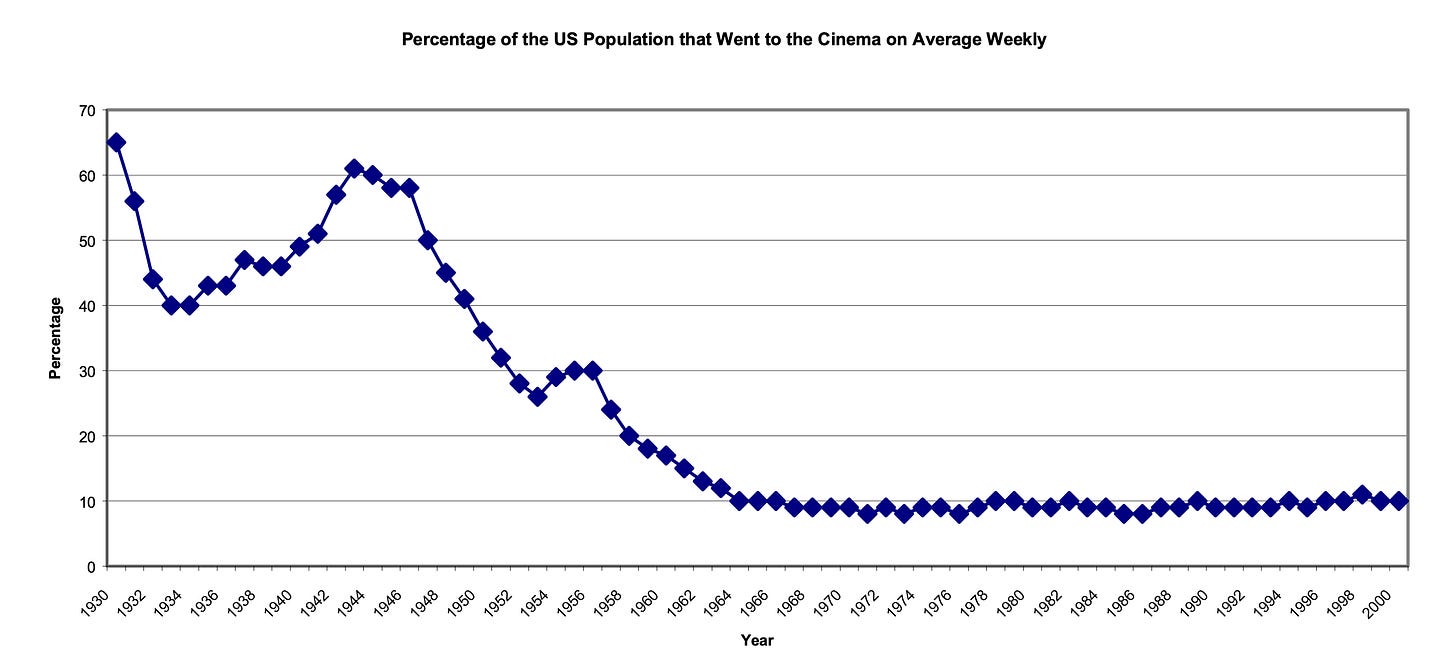

Cinema was cheaper and more scalable than theatre, and thus more accessible to the average person. “The Talkies” became so popular that by 1930, 65% of Americans were going to the cinema weekly, growing from 50 million ticket sales per week in the mid-1920s to over 110 million per week by the end of the decade. Cinema had supplanted theatre as the new pinnacle of entertainment.

Commentators proclaimed the end of theatre as viewership declined. To make matters worse, the timing coincided with the Great Depression. Actors and venues were forced to switch to cinema to find scarcely available work.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is certainly true that film made theatre more niche. But theatre did not die. Arguably, film made theatre a stronger medium with a more defined appeal. Theatres responded to the growing threat by refocusing on what made live performances unique.

Musicals, operas and classical plays never took off in film — there is some ineffable characteristic that can’t be recorded. You have to be there, and that spirit lives on today. The Lion King, The Phantom of the Opera, Wicked, Cats and Les Miserables have all since grossed more than $2 billion worldwide. Hamilton has grossed almost $1 billion, only 9 years after the first performance.

Still, film cameras gave rise to a new art form with its own unique strengths. Films made more kinds of stories possible, and they are better at immersing you in them. They enable directors to perfect a creative vision and preserve it in a single performance, while special effects bring the story to life in ways that aren’t possible on stage.

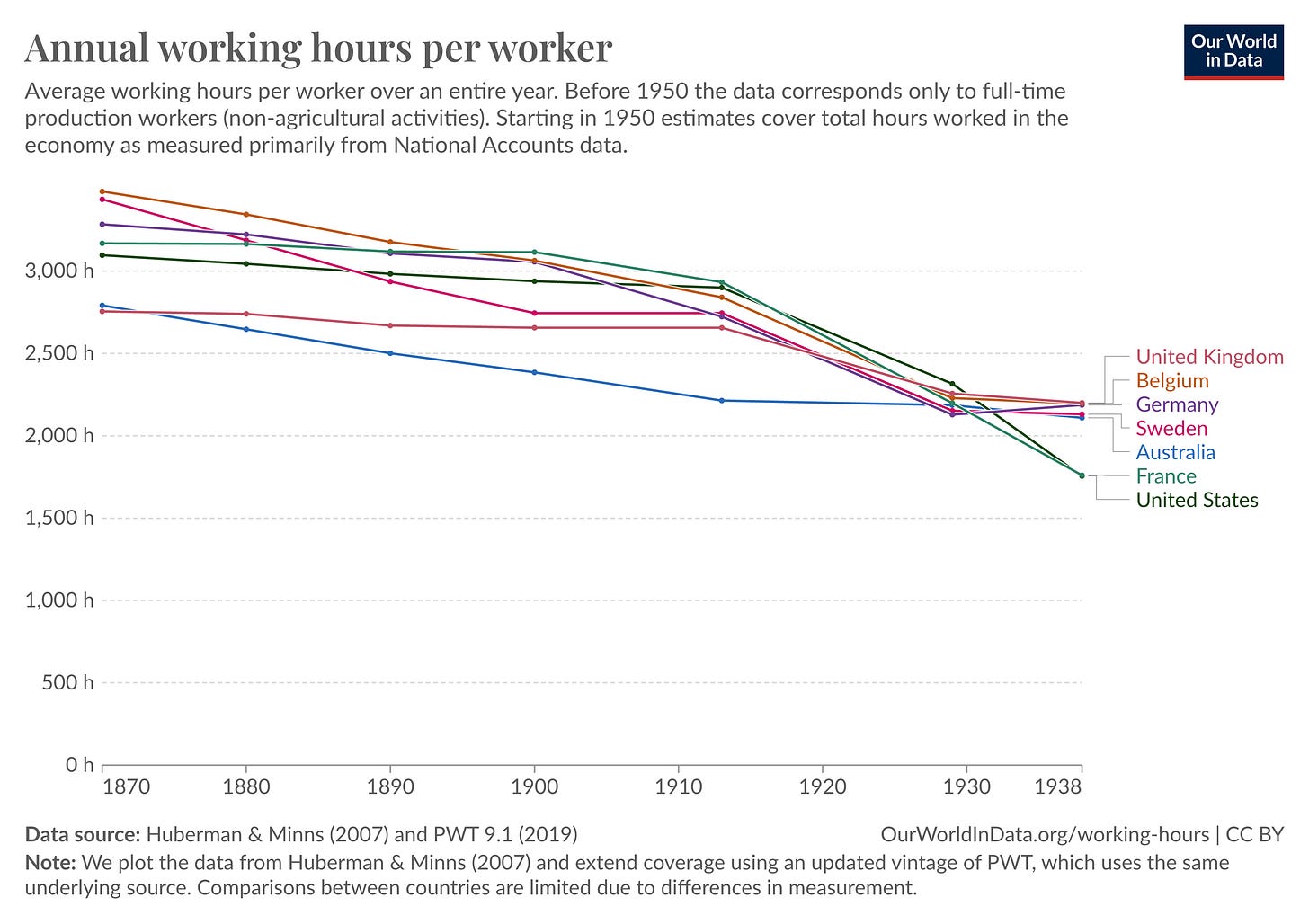

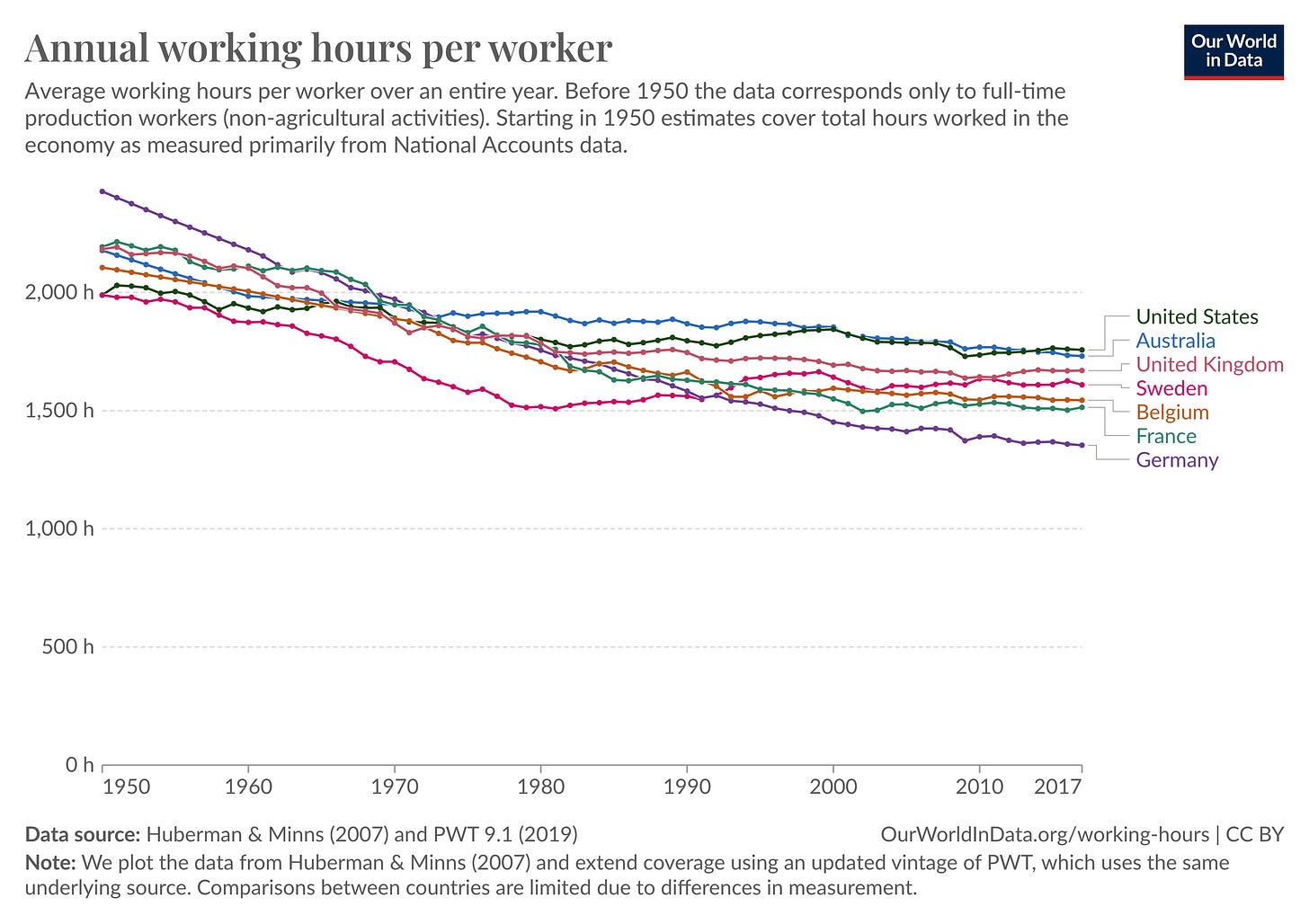

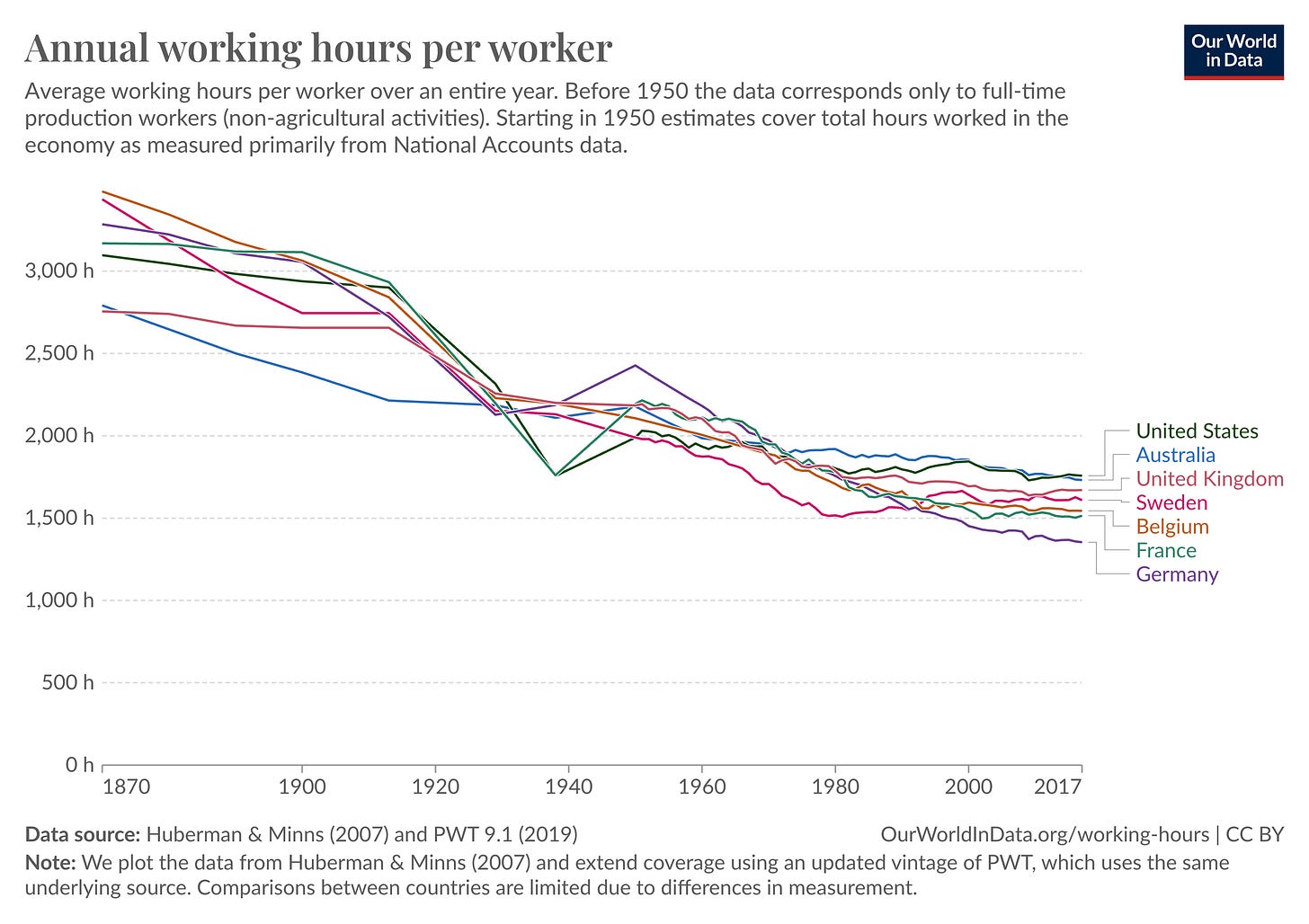

As a result, film captured a disproportionate share of the increase in average leisure hours through the late 19th and early 20th century.

Film ultimately got bigger than theatre ever did. In 2019, total revenue from the film industry was $101 billion, $42.2 billion of which was box office revenue and $58.8 billion home entertainment. Today, while cinema attendance is down, online video viewership has grown to an average of something like 17 hours per week. Including cinema and traditional TV, the actual number may well be more.

Celluloids and imaginary worlds

The evolution of cinema was primarily driven by film cameras and live action. But live action was not the only medium that came to prominence in this era.

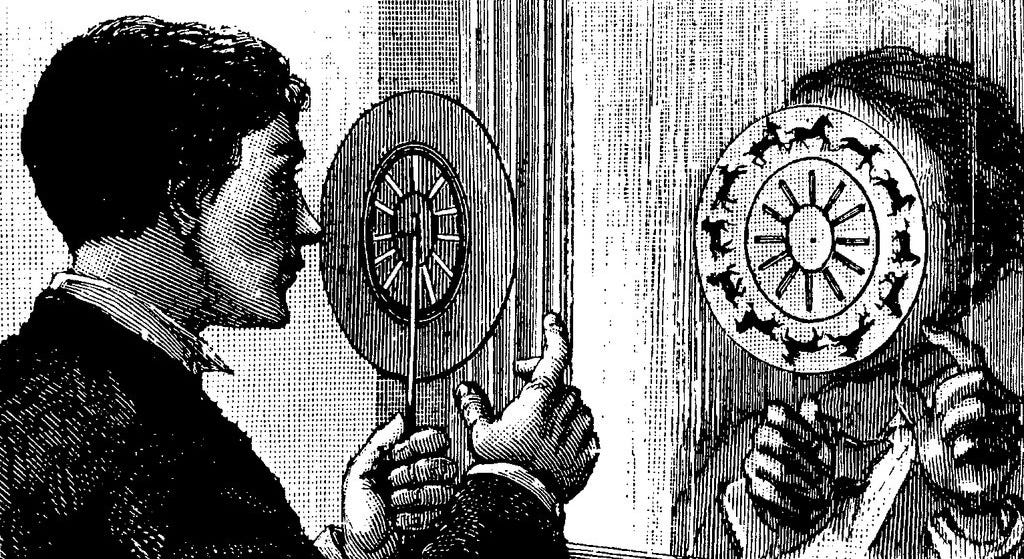

Animation can be traced back to the phenakistoscope, invented by Joseph Plateau in the early 19th century. It was a wheel mounted on an axel, on which sequential images were drawn. When viewed in the mirror through a series of slits, the motion blur was removed and the user would see the illusion of movement.

After the phenakistoscope, it would take another hundred years for animation technology to have its major breakthrough. By the early 1900s, the art had progressed to sequential drawings on sheets of rice paper, each photographed by the early cameras of the day. This enabled much greater complexity than phenakistoscopes, but rice paper presented its own logistical issues. Everything was hand drawn, and the opaqueness of the paper meant that common elements had to be redrawn for each new frame. Maintaining consistency across scenes was challenging, particularly for background elements which rarely changed across frames.

The major breakthrough came in 1914, with the invention of cel animation by Earl Hurd. Cel animation gets its name from its material. Instead of rice paper, scenes were hand-drawn onto transparent sheets of celluloid that could be laid on top of each other, preserving the background content. Now, complex scenes could be broken down into pieces and reused across frames without having to be redrawn. This massively reduced the cost and time associated with creating an animated film, while also enabling greater complexity and control for the animator.

Hurd refined his invention through the war period, introducing new innovations like pegs to keep cels in place during photography, and a system for layering cels and backgrounds efficiently.

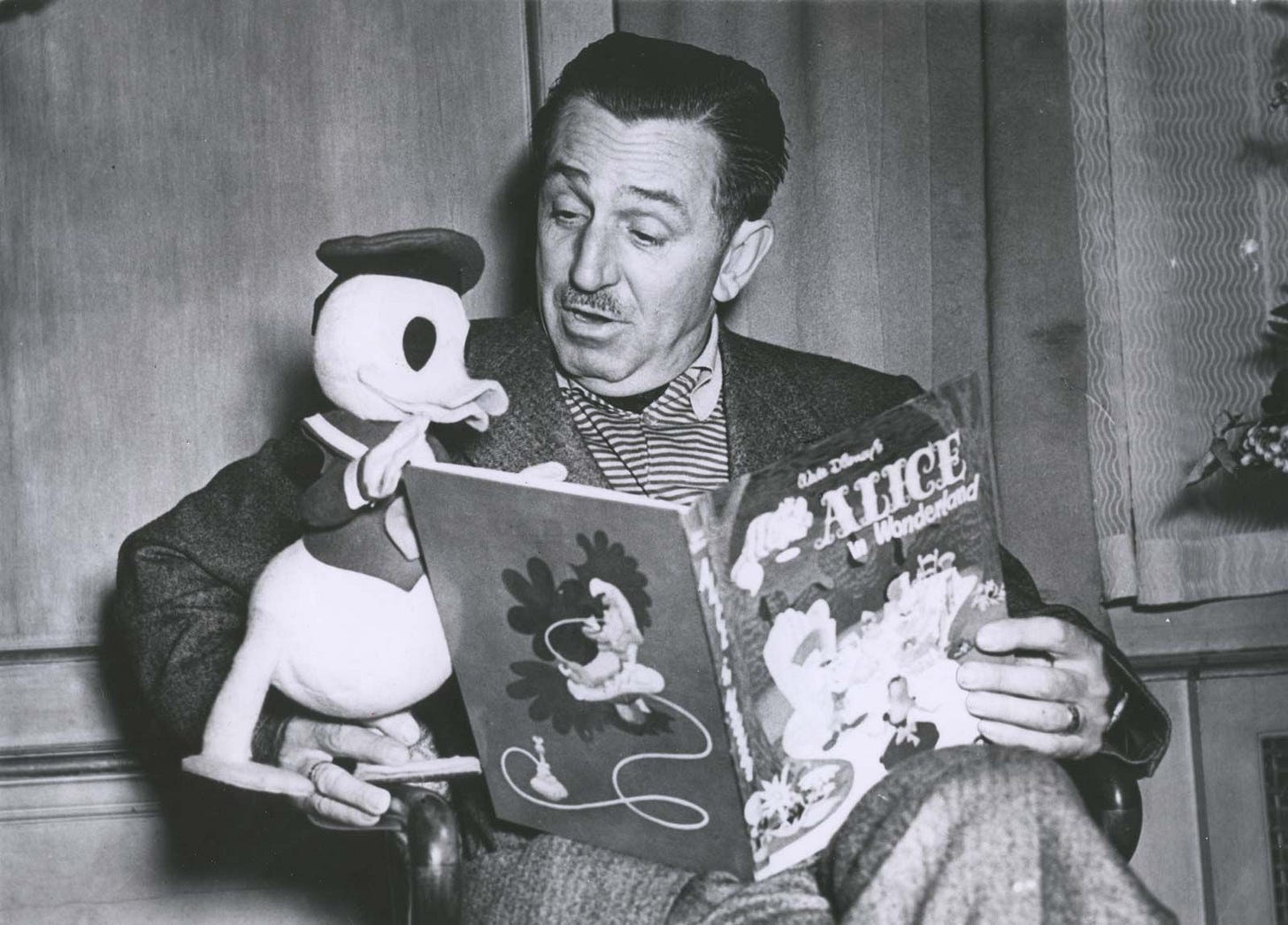

As animation technology was coming of age, so was a young Walt Disney. From an early age, Disney had shown talent as an artist, studying cartooning three nights a week at the Chicago Institute of Art in his teen years. After a stint driving ambulances in France at the tail end of the First World War, Disney returned to America seeking a career as a newspaper cartoonist.

His early career featured a series of odd-jobs and failed ventures as an illustrator. It wasn’t until he established the Disney Brothers Studio with his brother, Roy Disney, that the pair began to meaningfully work on animation. Disney Brothers secured a distribution deal with Winkler Pictures in 1923 to create the Alice Comedies, a series of short films about a girl named Alice and her adventures in an animated world. Over the next few years, the studio experimented with other ideas, the most successful of which became Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, often seen as the precursor to Mickey Mouse.

Much like Charlie Chaplin (and many great founders), Walt Disney sought total control in the development of his films. While he was recognised for his talent, he was difficult to work with even at the best of times. So despite its success, the years of developing Oswald the Lucky Rabbit had created tensions between Walt and Disney Brother’s employees, centred on his domineering personality.

At the time, as remains true today, studios and distribution companies were often separate, and Disney Brothers relied on an independent producer named Charles Mintz to distribute their films. Mintz brokered deals with the major film studios, and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit had been developed alongside Universal Pictures. Mintz had similarly grown tired of Disney’s controlling approach, and—seeing Walt as increasingly unnecessary now that he was no longer actively drawing frames—saw an opportunity to take control of Disney Brothers.

When the time came to negotiate a new deal for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, Mintz orchestrated a coup. Behind Disney’s back, he signed most of Disney Brothers’ animators to work for a new company under his control. Worse, Mintz acquired complete ownership of the IP for Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Mintz had Disney by the balls, and Disney knew it. Mintz walked away victorious, and Disney lost everything.

As the lore has it, it was on Disney’s train ride back from New York following this disaster that he drew the first versions of Mickey Mouse. Disney Brothers became the Walt Disney Company, and Mickey’s character evolved into Steamboat Willie. This was one of the first animated films with synchronised sound, benefitting from the same technology that enabled the release ofThe Jazz Singer.

At the time, animation was still the niche medium. Cinema viewership was through the roof, but most pictures were live action. Distributors had believed that animation was dead, and Disney initially struggled to find one. Exasperated, Disney agreed to a premiere at the Colony Theatre in New York, then an unusual move.

Disney’s gamble paid off. After losing everything just a few months before, Steamboat Willie was met with near universal acclaim, catapulting Walt Disney to global stardom as the leading figure in the emerging industry.

Steamboat Willie was first to demonstrate animation’s commercial promise. But while it had success at the box office, the real goldmine wasn’t just the ticket sales. Mickey Mouse quickly became a favourite with American children, and Disney recognised the opportunity for licensing merchandise. A plethora of watches, ice cream cones, toys—everything you can imagine— followed. Disney had found a way to keep the magic of the Mickey Mouse story going even after the film was over, contributing the lion’s share of Disney’s $600,000 in yearly profits by 1934 (~$14 million in 2024).

New technologies like technicolor, multiplaning and rotoscoping were introduced in the 1930s. Disney, always seeking to push the boundaries, wanted to follow the success of Steamboat Willie and Mickey Mouse with the first feature-length animated film. After 3 years of development, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was released in 1937, grossing $19,000 in its first week (~$410,000 in 2024), rising to $180,000 in its first 10 weeks (~$3.9 million in 2024). By 1939, it had become the highest-grossing American film to date with $6.7 million in box office revenue (~$150 million in 2024).

For some time, animation had been considered the niche medium. But after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, animation was finally established as a major cinematic art form. Looking back, the reason is obvious — Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs could never have happened as a live action film. Cameras are, by definition, a reflection of reality. To take a picture, the scene has to be plausible inside of the real world and its physics. But celluloid sheets enabled a new medium that was not bound by reality’s limitations; offering imaginary worlds with new storytelling possibilities that cameras alone could never capture.

As it turns out, those imaginary worlds have become some of the most popular and enduring IP in the world. Disney has grossed more than $100 billion just in the Mickey Mouse and Disney Princess franchises.

Animation as a medium has a unique way to tell stories and create relationships with an audience. The characters never age and easily translate to merchandise and costumes, while the stories can be continually updated to reflect new conditions. Most parents and grandparents today will remember their experiences with Mickey Mouse as a child just as vividly as their children and grandchildren.

It’s not just Disney — we also have the medium to thank for Looney Tunes, Tom and Jerry, Scooby-Doo, The Flintstones and The Simpsons. And cel animation gave rise to computer animation, which we have to thank for Toy Story and all of Pixar’s masterpieces. It has made the world more joyful, and we are better for it.

Microprocessors and video games

Films grew to maturity through the 50s and 60s. Cinema attendance was, however, on the decline as television brought screens into the home. Meanwhile, a post-war boom in consumer spending power created more budget for leisure activities, and we saw another significant increase in free time.

At the time, computers were still early. They were big and unwieldy — the most powerful were room-sized and required teams of skilled operators. The personal computing revolution had not started yet, nor had its impact on entertainment.

In 1971, Intel released the Intel 4004, the first commercially available microprocessor. Computers had previously relied on multiple discrete components (transistors, diodes, resistors etc) to perform logic operations. Microprocessors integrated many transistors along with other components on a single chip, dramatically reducing the device footprint and power consumption.

Microprocessors were important for so many reasons. One of them was that, roughly speaking, the microprocessor was to video games as Le Cinematographe was to film. Suddenly, there was a cost-effective and programmable platform for writing game logic and graphics, in a small enough package to build compact devices for user input.

Arcade machines were the first generation of video game consoles, with microprocessors at their core. Atari released Pong in 1972, leading to an arcade craze that saw classics like Space Invaders, Asteroids and Pac-Man through the end of the decade. Space Invaders became one of the highest-grossing entertainment products of all time, grossing $3.8 billion by 1982 (~$12 billion in 2024).

This was the era were Japanese manufacturers were beginning to dominate consumer electronics, and most of the emerging video game manufacturers were Japanese. Think Atari, Taito, Capcom, Sega, Namco and Konami. Together, they were starting to hit the motherload by exporting to the American market.

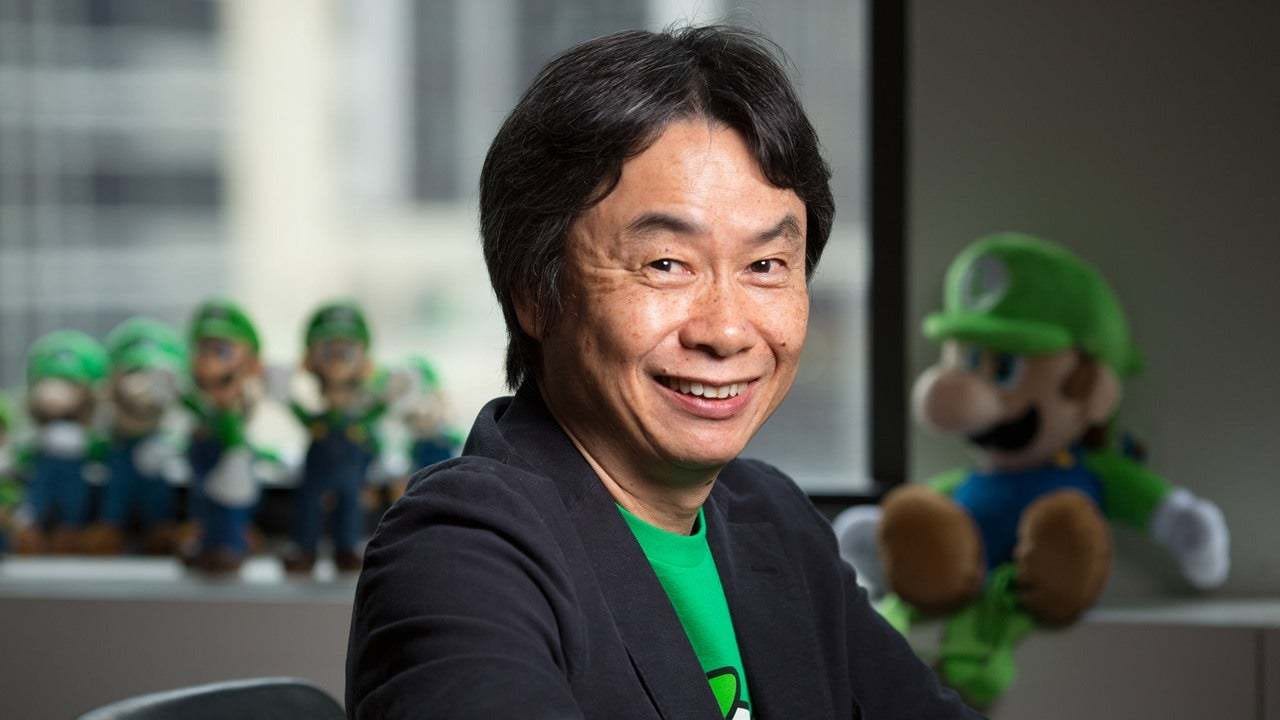

Nintendo emerged as the leader of this crop. Despite being founded as a playing card manufacturer back in 1889, Nintendo’s lasting success came with video games. This success can be largely traced to a single person. Shigeru Miyamoto is now arguably the most revered game designer of all time, having played a role in the development of almost all of Nintendo’s major IP franchises. He is directly responsible for the Mario and Zelda universes, and oversaw the introduction of Pokemon and Metroid Prime. Quite a track record.

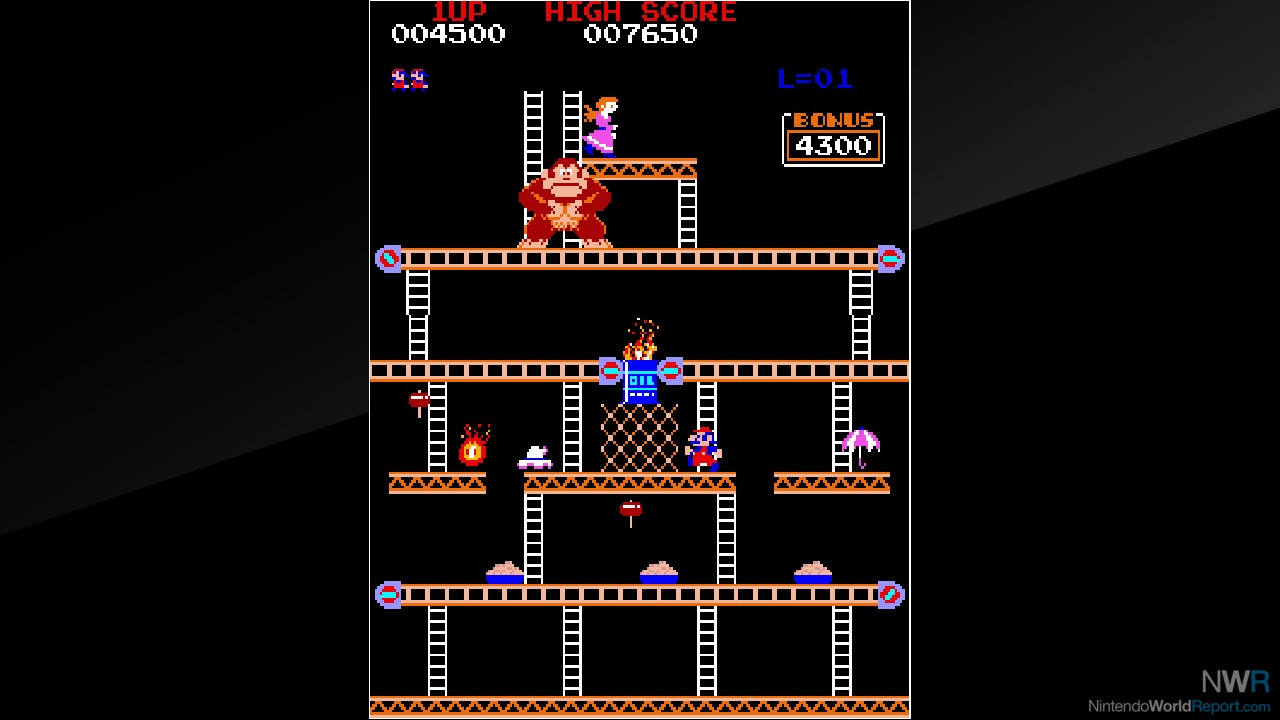

Miyamoto joined Nintendo in 1977, then 25 years old. At the time, arcade games were all platform games — simple levels where the character has to navigate a series of obstacles to reach a goal. Miyamoto saw this as a missed opportunity, believing that games had huge potential for engrossing storylines. Like all great ideas, this seems incredibly obvious now despite being clearly non-obvious at the time. So when he was given the freedom to begin developing his first game, Donkey Kong, this was the approach he chose to pursue.

Games are a trigger for adults to again become primitive, primal, as a way of thinking and remembering. An adult is a child who has more ethics and morals, that's all. — Shigeru Miyamoto

His original plan had been to license the Popeye franchise — the very same spinach-chomping Popeye that you know. The basic premise of Popeye is a series of battles between Popeye and his adversaries. Most notably Bluto, with whom there is a love triangle with another character, Olive. But Nintendo could not secure the license, and Miyamoto was forced to rethink. Sticking close to the original love triangle, Miyamoto replaced Olive with Pauline and Bluto with Donkey Kong. Jumpman, initially based on Popeye, would evolve into Nintendo’s most iconic character, Mario.

Donkey Kong was the first arcade game to have a sophisticated plot. In a storyline that is also reminiscent of King Kong, Donkey Kong escapes his cage and kidnaps Pauline, carrying her to the top of a construction site. Jumpman seeks to save her, and must climb over increasingly difficult obstacles to win the game.

Donkey Kong was an instant hit. It grew rapidly and sold over 60,000 arcade machines and earned over $180 million in revenue in its first year.

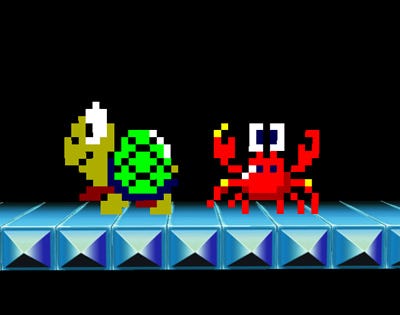

After following up with two sequels, Miyamoto moved onto creating Mario Bros, the first game featuring Mario as a named character together with his brother Luigi. Together, they are tasked with clearing New York’s sewers from a series of now-legendary enemies, like the shellcreepers, sidesteppers and fighter flies.

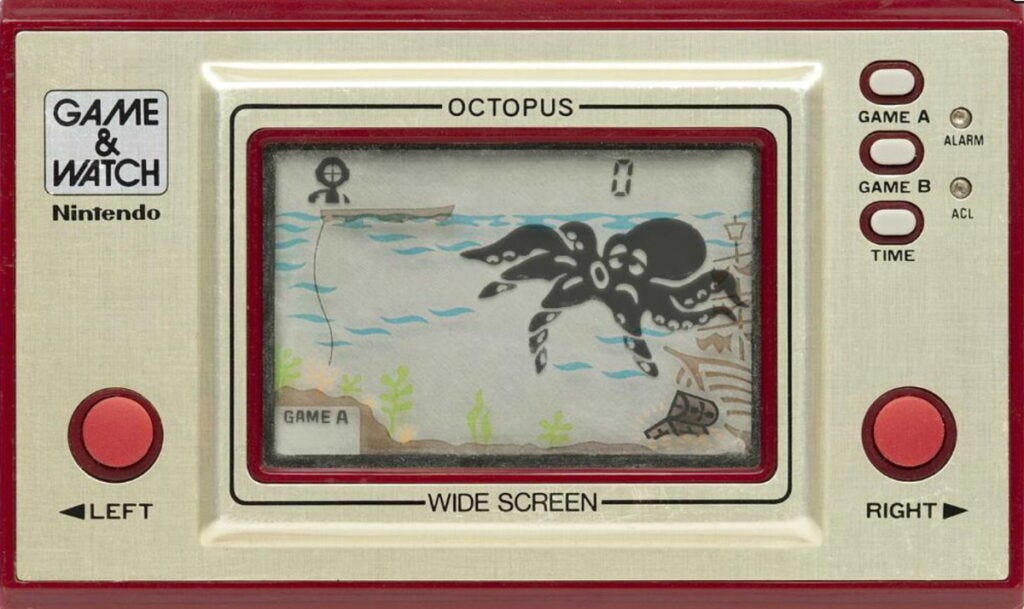

With Mario Bros and Donkey Kong, Nintendo found early success in arcade games. But arcade games were only a phase, and Nintendo’s dominance grew through the manufacture of smaller consoles. Following the Color-TV Game, Nintendo delivered the Nintendo Game & Watch in 1979. This was the world’s first handheld gaming console, featuring an LCD screen and a simple control setup. Each device was dedicated to a single game built into the hardware.

Nintendo sold more than 43 million units through the 1980s, raking in almost $2 billion in revenue (~$5 billion in 2024) across 59 titles, and this set the stage for their early console dominance. Nintendo subsequently released the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in 1983, followed by the the original Gameboy (1988) and the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) in 1990. This was Nintendo’s first golden era, during which they owned 65% of the console market ahead of rivals Atari.

Throughout, Nintendo continued their legendary IP binge, producing Super Mario Bros and The Legend of Zelda on the NES and Pokemon Red/Blue on the Game Boy. Miyamoto was at the centre of all of them. These originals remain some of the most loved, best rated and best-selling games of all time.

Video games offered something very different to prior mediums. Film and animation are both static and predetermined. The outcome is the same every time, and the consumer has no power to influence the story. Games, on the other hand, are about participation from players rather than viewers.

We are surrounded by decisions and, therefore, games in everything we do. Interesting might be subject to personal taste to some degree, but the gift of agency, that is the ability of players to exert free will over their surroundings rather than obediently following a narrative is what sets games apart from other media. — Sid Meier

Today, gaming is increasingly social. What started as ‘co-op’ with an extra controller has become massively multiplayer environments like Fortnite, Minecraft and Roblox. Games excel at social because game dynamics can make active cooperation intrinsic to gameplay — something that isn’t possible in other mediums.

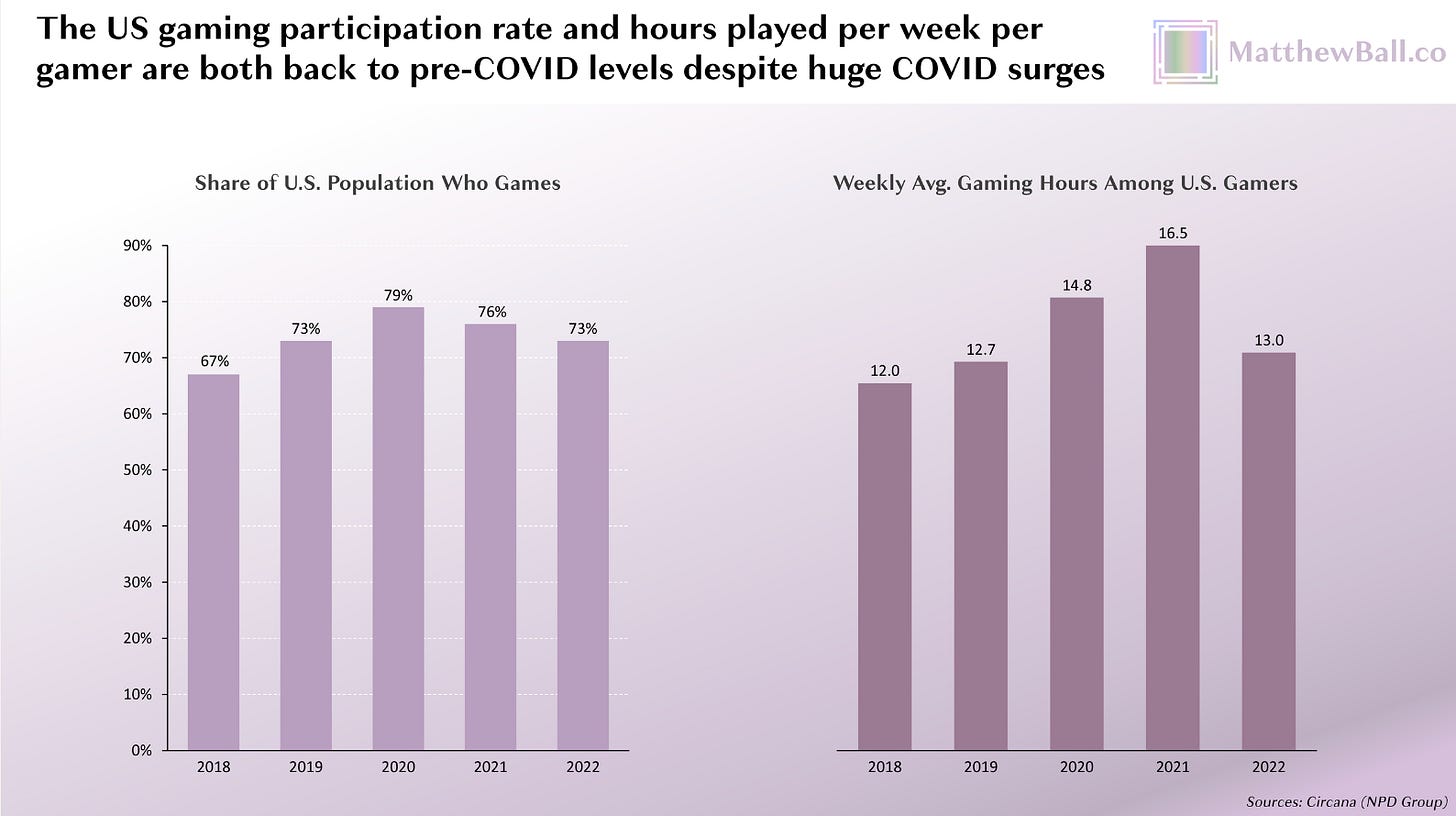

Like film did in the early 20th century, games captured a disproportionate share of the increase in leisure time. Though the number has come down from COVID highs, the average person today spends around 13 hours per week playing games, with roughly three-quarters of the US population registering as gamers. It’s hard to say exactly how much this overlaps with video viewership, but they are likely at least partially additive.

In total, the gaming industry now generates $187 billion/year. It is possible that as video games continue to mature as a medium and the Fortnite generation grows up, video games will become the primary entertainment medium in the same way that films overtook theatre.

Still, this won’t make games ‘better’.

Agency enables game experiences that wouldn’t make sense in another medium, for sure. But despite Miyamoto’s original insight, games have never matched film in depth of storytelling. There are only a few exceptional games where the story rises above the gameplay, like The Last of Us, Red Dead Redemption and Bioshock.

The mediums are good at different things, and they are both uniquely valuable. An increase in the number of leisure hours means that there is space for both.

AI will help make a new medium

Looking back, new mediums emerge around new tools. This has happened many times in history, including the emergence of cinema, animation and video games.

Each time, the new medium has some unique characteristic that goes beyond prior art. Before the fact, you could be forgiven for believing that films would just be recorded theatre, animation would just animate live action figures, or video games would just make films first person playable. But this wasn’t what happened. Instead, each created a unique art form that the previous medium could not capture, inviting a new generation of artists to explore its creative potential.

AI is a new tool that enables specific new creative possibilities. Yet today, we are mostly thinking about how AI can improve the state of the existing creative arts. We are talking about “AI images”, “AI films” and “AI video games”. However, the ultimate destination of AI is to help produce a new medium that maximises its creative potential beyond those built for bygone technology.

McLuhan said that “the content of a medium is just another medium”, and that will probably be true here. The generative medium is going to include aspects of all the other mediums combined. But they are going to combine to create something novel. Something more akin to building worlds, complete with immersive environments and interacting user-led narratives.

Maybe we’ll call the experiences “dimensions” or “verses”. Maybe we’ll call the artists “worldbuilders”, “architects“ or “dimensioneers”.

History shows that people have an essentially limitless desire to be immersed in stories. The only limit is the tools we have to tell them, and the free time we have to participate. AI affects both — it provides new tools, and will change the nature of work to liberate yet more time for leisure.

If you can bet on anything in a future of mass automation, it is that the human need to participate in stories is not going to change. Instead, it is going to grow. Stories are going to become more important as we seek meaning outside of the kinds of work that we did in the early internet age. This is just a continuation of a longstanding trend.

My bet is that the new medium will once more capture a disproportionate share of the newly available leisure time. Eventually, it will grow to become the primary entertainment medium as it leverages emerging platforms and caters for the younger generations for whom it comes most naturally.

Of course, don’t be fooled into believing that this will suddenly become the only medium. Films did not kill musical theatre, and video games did not kill film. New mediums are about exploring new capabilities, not destroying prior arts.

Still, if you are so inclined, you should strongly consider the new medium. The tools are starting to arrive, and this is probably the greatest artistic opportunity of the 21st century. In 2100, the Charlie Chaplins, Walt Disneys and Shigeru Miyamotos of the world won’t have made their names creating films or video games. They’ll have made them creating worlds.