AI media and the enchanted rose

New tools create new markets

In the story of Beauty and the Beast, an old beggar woman requests shelter from the bitter cold at a prince’s castle. She offers the prince a beautiful rose. The prince, seeing her haggard appearance, rejects the gift and turns her away. Slighted, the woman reveals herself as an enchantress and curses the prince, transforming him into a hideous beast.

She leaves him the rose, promising that it would bloom until his twenty-first birthday. If he could learn to love another and earn their love in return before the last petal falls, the curse would be broken. If he failed, he would be doomed to remain a beast for all time.

In 2024, humanity is the prince and we have been bestowed a beautiful gift. It comes in the form of AI. As the weeks go by, new tools are arriving and with each new medium they conquer, their role in the future is becoming increasingly clear.

Despite its promise, many seek to reject this gift. They say it will destroy our livelihoods. They say it will it bring the end of art and the end of artists. Looking back, it always seems to be this way — the golden age is always in the past and technology is always here to destroy it.

New technology has threatened old mediums before, creating new markets and minting new artists that the previous generation of tools could not serve. But each time, holding onto the past is much like the enchanted rose. Accept its magic, and you will be rewarded. Decline, and you will be forever cursed.

One way to look at today’s image models and video models is a new kind of camera. Through the history of photography, we have faced moments like this before, and we can learn a lot from understanding how those moments turned out. So this is a tale of three men, three companies and three major transitions in photographic technology, and a reminder that although we are in a new generation, it’s still an old story.

Edwin Land, Polaroid and the rise of instant photography

Cameras first emerged in the first half of the 19th Century. As you might expect, they were bad, bulky and difficult to use, requiring long exposure times and complex manual development processes. Photography was thus highly professionalised among a few skilled operators, and their services were only available to the few who could afford the high labour costs.

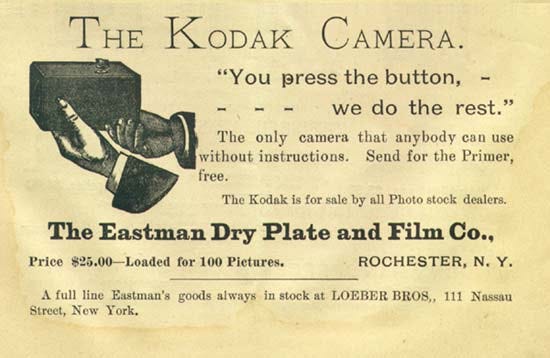

The first major transition came in 1888, when George Eastman of the Eastman Kodak Company launched the Kodak No. 1 camera. Priced at just $25 (~$1000 in 2024), it came pre-loaded with a roll of film for 100 exposures in a portable form factor. Once the film was full, customers sent the camera back for development and received a reload with finished photos a few weeks later.

Kodak’s innovation made photography an order of magnitude simpler. Successor devices like the Kodak Brownie refined the offering at much cheaper prices, helping to create a new crop of photographers unable to participate in the complex and expensive methods of the past. Kodak’s reward was to build a reputation around their famous slogan.

You press the button, we do the rest.

Of course, in practice, taking good photographs was still hard and the cost still prohibitive relative to average income in the early 20th Century. While the number of photographers was larger than it had been in the 19th Century, photography remained largely professionalised until the mid-20th Century, following a post-war boom in consumer spending power.

It was during this time that a then-young man named Edwin Land arrived on the scene. Land was an early example of today’s typical Silicon Valley darling story. Gifted child who built contraptions in his parent’s garage; iconoclastic Harvard dropout who refused to bow to authority; uncompromising founder and prolific inventor.

Land’s first invention was the polarising filter. To this day, it remains a critical component of modern sunglasses, screens, cameras and more. While a scientist to his core, Land quickly sought commercialisation of his invention and established Land-Wheelwright Laboratories in 1932 with his Harvard physics instructor.

Don’t undertake a problem unless it is manifestly important and nearly impossible. — Edwin Land

As Land’s commercial appetite grew, Land-Wheelwright Laboratories evolved into the Polaroid Corporation in 1937. Polaroid initially focused on applying polarising filters to a range of optics use-cases. It wasn’t until the Second World War, during which Polaroid became an important research partner to the US government, that Polaroid’s focus shifted to the camera business.

As the lore has it, Land’s daughter originally posed the problem on vacation in 1943. Upon taking her first photograph, she innocently asked why the photo was not printed immediately. Land obsessed over the problem for the next four years, and Polaroid delivered their first camera in 1947.

One day when we were vacationing in Santa Fe in 1943 my daughter, Jennifer, who was then 3, asked me why she could not see the picture I had just taken of her. As I walked around that charming town, I undertook the task of solving the puzzle she had set for me. Within the hour the film, and the physical chemistry had become so clear that I hurried to the place where a friend was staying, to describe to him in detail a dry camera which would give a picture immediately after exposure. — Edwin Land

The Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 was the world’s first instant camera, using a new chemical process to produce finished photos directly from the camera in just a few minutes. It was far from perfect, but it was faster and easier to use than the professional cameras of the time. And so much like Kodak before them, Polaroid was poised to create a new kind of photographer.

Polaroid spent the 50s and 60s refining the instant camera. New models and colour film saw instant photography grow significantly among consumers. This emerging market did not care for the complexities of professional photography. The new generation wanted to point, shoot and see the result immediately.

Land understood this better than anyone. He envisioned a pocketable device that was so simple, fast and cheap that photography would become a normal part of everyday life. This was Polaroid’s niche, enabling playful new use cases that incumbent Kodak could not.

One in particular became famous. Since Polaroid’s cameras developed photos on-device, they were private for the first time. Yes — just as Land is one of America’s most decorated scientific inventors, he also has some cultural cachet as the inventor of the dick pic.

[cameras] would be, oh, like the telephone – something you use all day long … a camera that you would use as often as your pencil or your eyeglasses — Edwin Land

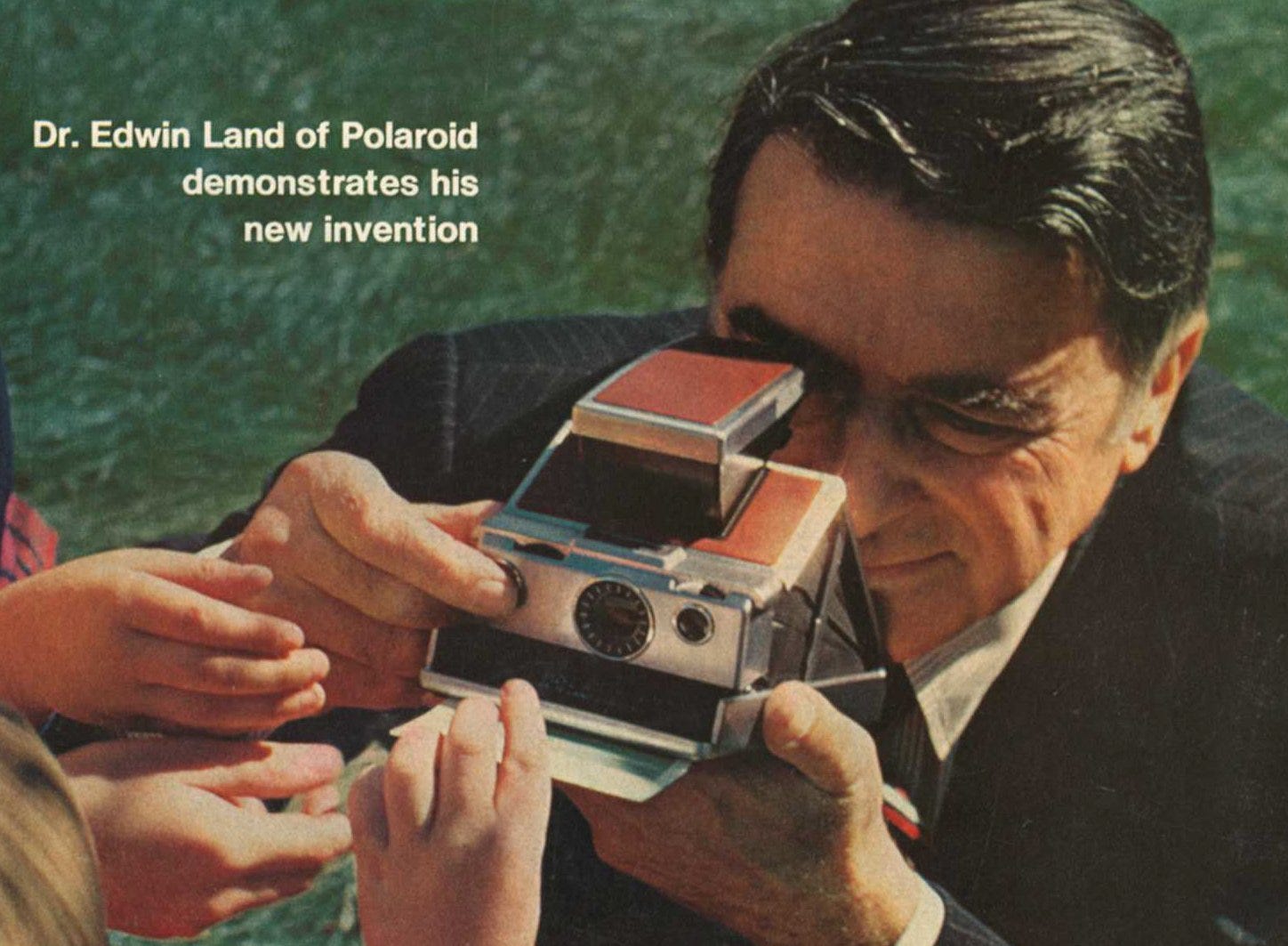

The deliverance of Land’s vision came in 1972, with the launch of the SX-70. It’s folding single-lens reflex (SLR) design meant that it (nearly) fit in a coat pocket while also enabling high performance. Where previous models required additional manual steps to finish the photos, the SX-70 printed finished photos automatically. And so despite early production issues, the SX-70 became a cultural icon.

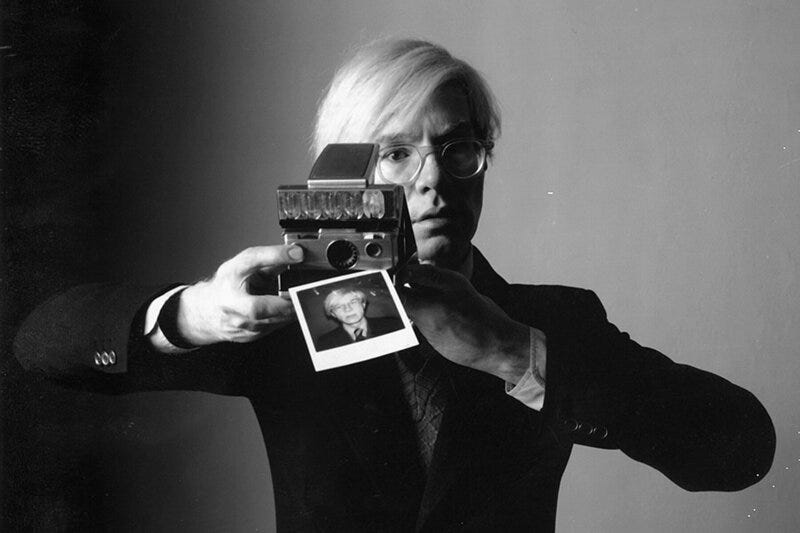

In the art world, some embraced the new medium. Artists like Chuck Close, Walker Evans, David Hockney, Robert Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton, Andy Warhol and Ansel Adams cited its ease of use, editability and the novel opportunities it opened up.

I think anybody can take a good picture. My idea of a good picture is one that's in focus and of a famous person doing something unfamous. It's being in the right place at the wrong time — Andy Warhol

It was shocking, after six years of college art to be so attracted to the point and shoot, but it in fact satisfied everything that I needed at the time….The camera was magic to me. — Norman Locks

But this reception was far from unanimous. By this point, photography was a maturing medium with more than 100 years of history. Instant photography was the first big challenge to the old way of doing things.

Those invested in the old way said it wasn’t real photography. It didn’t count. They argued that it destroyed artistic integrity, threatening the skilled work of darkroom development and the livelihoods of those who spent years honing their abilities. Some even argued that the immediacy separated users from ‘the moment’ — the focus becoming the printed image rather than the reality it represented.

Perhaps they were right. Because it was a new kind of photography for a new kind of photographer, inspiring new ideas not limited to the dusty and high-minded expectations of the past.

Even with Polaroid’s success, Kodak remained by far the most important camera company in the world. As of 1975, it was estimated that Kodak controlled 90% of the conventional amateur film market and 85% of the consumer camera market, with a total revenue of ~$5 billion (~$29 billion in 2024). Instant photography was a fraction of this number, with Polaroid’s revenue reaching only ~$800 million in that same period. And so for most of Polaroid’s rise, Kodak viewed instant photography as more of a curiosity.

Despite their commanding position, the introduction of the SX-70 saw Kodak’s position change. No longer seeing Polaroid as just a toy, Kodak was beginning to see instant photography as both an opportunity and a threat. So when Polaroid offered the chance to supply the film for the SX-70, Kodak declined and chose instead to begin developing their own instant camera.

Of course, Kodak had no prior experience in instant cameras. Polaroid, on the other hand, had spent almost it’s entire lifetime creating instant cameras. Land himself had invented most of the technologies that made it possible, with a total of 535 patents to his name — third only to Edison and his protege at the time. To say that Polaroid had a head start would be an understatement, something that Land studiously recognised while seemingly eluding Kodak’s entire executive team.

I'm the last person in the world to undersell or underestimate Kodak… but we are so far out ahead in conceptualization and insight and understanding, and in patents, that we can not only hold the lead but move out well, well-ahead of everyone else in the domain of instant photography. — Edwin Land (Testimony from the Kodak vs. Polaroid trial, via A Triumph Of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid, And The Kodak Patent War)

If it wasn’t clear before, the SX-70 revealed the gulf in technology. Kodak’s first instant camera was quickly cancelled before launch citing the prototype’s obvious inferiority. Determined, and increasingly panicked, Kodak returned to the drawing board and created a new internal program to build an SX-70 killer. Internal documents now show that employees understood, even at the time, that Kodak could at best create a copycat. But they proceeded, and in their apparent desperation, began encouraging engineers to use Polaroid’s patented technology.

We see no unique consumer benefits in the proposed Kodak program at this time. — Kodak (An internal report filing, via A Triumph Of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid, And The Kodak Patent War)

The project was a meagre success — Kodak delivered a line of instant cameras in the late 70s, including the EK4 and EK6. But it had little impact on their bottom line, and came at a much more significant cost.

Seeing the obvious similarities in technology, Polaroid filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Kodak. The ensuing legal battle was bitter and lasted for almost 10 years, in what remains one of the most famous corporate legal cases of all time. Polaroid argued that Kodak infringed patented technologies to produce their instant cameras. Kodak argued that Land’s patents were invalid, mostly recapitulations of earlier ideas, and thus were not enforceable.

In another situation, Kodak’s strategy may have paid off. But the core accusation was that Land’s life’s work was a hoax. For Land, it was deeply personal. And there are some people in this world for whom you do not want to make it personal. Famous inside Polaroid for a forceful and relentless personality, and outside as the world’s foremost expert on instant photography, Land outclassed Kodak’s legal team as a star witness and was crucial in proving the falsity of their claims.

The result was a decisive victory for Polaroid. Kodak was ordered to cease manufacturing and distributing their instant cameras and film, effectively ending their involvement in the instant camera market. Polaroid grew to control the instant camera market largely unchallenged. Kodak was also ordered to pay damages amounting to $925 million in the final settlement (more than $2 billion in 2024). This remains one of the largest settlements for patent infringement in American corporate history.

As was the rise of Edwin Land, Polaroid and instant photography. Land remains one of America’s great inventors and entrepreneurs. Through Polaroid, his impact was to inspire a new market of consumer photographers that could not be served by the older generation. But it would take new technology and a new generation of companies to truly exploit it.

Changing of the guard: Akio Morita, Sony and the transition to digital photography

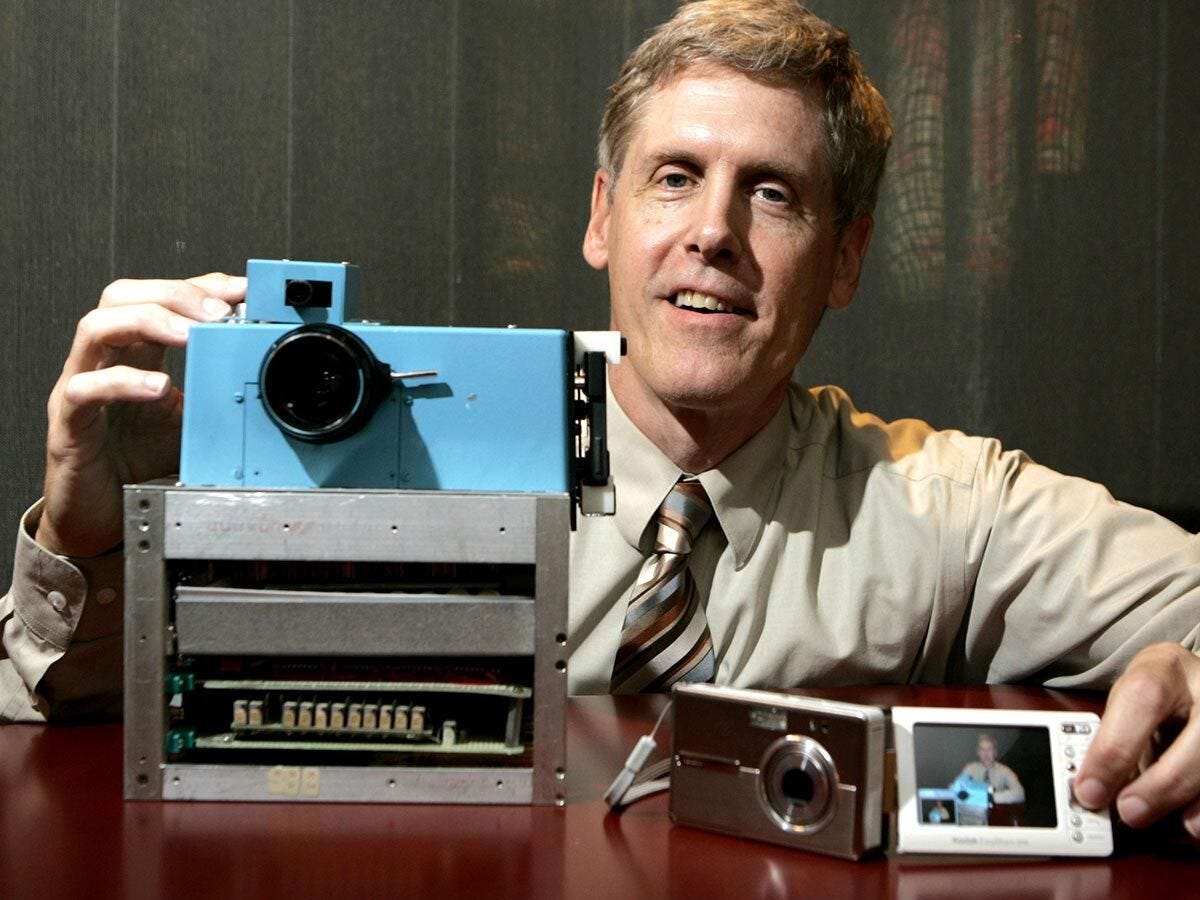

While Kodak and Polaroid fought over instant cameras throughout the 1980s, the technology was already outdated. Digital photography was now the new kid on the block. Ironically enough, Kodak itself was the creator of the first digital camera in 1975, the year before releasing the EK4 instant camera. It acquired several patents and established what should have been a dominant early position.

As we know, of course, digital cameras proved to be the fatal blow for Kodak. In what is strangely reminiscent of the current moment, years without conviction, strategy and a strong leader led Kodak to squander one of the great technology premierships.

Meanwhile, Polaroid was experiencing its own turmoil. Land was a particularly single-minded autocrat. He was deeply committed to innovation even at the expense of Polaroid’s financial success. Despite being the founder and lead inventor, his idiosyncrasies and financial missteps saw him subject to increasing disrespect among his fellow executives.

Land is like a bear. You can admire the bear. You can do things with the bear. But you have to be very careful not to be eaten by the bear. — Peter Wensberg (former Polaroid exec)

Around the late 70s, video cassette recorders (VCRs) were starting to become popular. VCRs enabled the evolution and distribution of pre-recorded content, with feature-length recording times and playback on home devices. Home videos were growing as a market, leading to the founding of Blockbuster in 1985 and the emergence of camcorders as consumer recording devices.

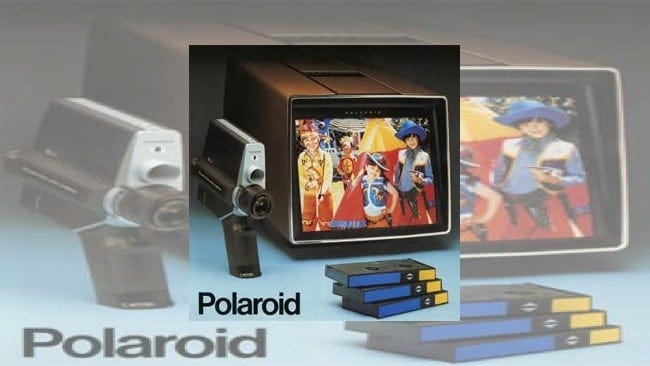

Under the umbrella of Polaroid’s R&D department, Land had invested years and hundreds of millions of dollars into Polavision, Polaroid’s entry into the home movie market. Polavision was a dual-use product, enabling video recording with a camera and playback of those videos on a separate screen device via a proprietary film format.

Land had not seen VCRs coming, and Polavision lagged in key respects — shorter recording times, lack of compatibility with the ecosystem and a small playback screen. The ecosystem grew around VCR, and Polavision was consigned to commercial failure. The financial fallout exacerbated existing tensions, catalysing Land’s exit from the company he founded. Land resigned as CEO of Polaroid in 1980, and left the board of directors in 1982.

Akio Morita, founder of Sony and friend of Land, had warned that Polavision was a decade too late shortly before launch. Morita saw the writing on the wall because he, unlike Kodak and Polaroid, was one of the few to correctly understand the industry’s future direction.

Morita had come of age in a war-ravaged Japan. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were wiped out, while most of Japan’s major industrial cities were reduced to wastelands. Tokyo was a shell of its former self, with less than half of the pre-war population remaining in the city.

Morita, a student and professor of physics, was one of many young Japanese tasked with rebuilding a broken economy. No mean feat, given Japan’s lack of natural resources, non-existent manufacturing base and historical reputation for producing poor quality products.

Sony’s rise was thus all the more remarkable. But their beginnings were humble; originally an electronics shop inside a department store under the name Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo. Morita ran it alongside his friend Masaru Ibuku for years before experiencing their first real success. That came in the form of the TR-55 transistor radio, which fueled expansion into the American market and drove Sony’s sales from a mere 100,000 in the late 50s to over 5 million in 1968. This laid the foundation for the Sony Walkman, first released in 1979, which went on to sell over 400 million units and propel both Sony and Morita to international stardom.

Sony formed part of Japan’s sensational rise as an economic force in the 1980s. From practically a zero-start just 40 years earlier, Japan became a manufacturing superpower that came to dominate industries that America had previously controlled, especially cars and consumer electronics. Manufacturing began to move offshore, as Japanese upstarts outcompeted American incumbents.

Following Sony’s success in audio, Morita saw the promise of digital photography. He saw its capacity for automation, better storage and integration with the growing world of computers. With Polaroid facing financial difficulty under new leadership, Kodak taking a series of strategic missteps, and Japan emerging as the world’s electronics factory, Sony was poised to lead a new transition from film to digital.

Our plan is to lead the public with new products rather than ask them what kind of products they want… The public does not know what is possible, but we do. — Akio Morita

Sony announced the Mavica, it’s first digital camera, in 1981. Consensus among Polaroid, Kodak and most of the incumbent photography industry was that it would fail due to high prices and lack of consumer demand. It was believed that digital photography would not work until at least the 90s, and that resources were best spent on existing product portfolios.

In some sense, this was correct — the original Mavica was never launched and digital photography did not really take off until the late 90s. But the sentiment diverted investment away from the budding technology while there was still time to build a position. Polaroid declined to partner with Hitachi, while Kodak’s internal digital development atrophied.

Once again, it wasn’t just incumbent companies who wrote the new technology off. Leading artists, filmmakers and photographers alike decried digital devices as a denigration of a precious art. Digital photographs could not be ‘trusted’. They were ‘too easy’. They disrespected a long history that had minted a generation of heroes.

You've no need to believe a photograph made after a certain date because it won't be made the way Cartier-Bresson made his. — David Hockney

As far as I'm concerned, digital projection is the death of cinema as I know it. — Quentin Tarantino

I think, truthfully, it boils down to the economic interest of manufacturers and [a production] industry that makes more money through change rather than through maintaining the status quo. — Christopher Nolan

This continued into the 2000s. It was believed that journalistic integrity was at stake; that cinema was dying. Of course, digital devices did enable new means of forging photographs. They did enable new filming techniques that outcompeted, and to some extent, displaced traditional cinema. But think of all the incredible projects that couldn’t have happened without digital technology. Christopher Nolan aside, how many films would have been impractical because the effects were too expensive? How many countless photoshoots, articles and books would have suffered?

The reality is that digital cameras reduced costs, simplified storage and improved editing capabilities for everyone. Most importantly, they expanded both the number of people involved in these industries and the volume of art produced. Few would seriously make a case now that digital was not a massive net positive.

Sony seized the opportunity, and went on to become one of the world’s leading manufacturers through the 80s and 90s. Where Kodak and Polaroid had been quintessentially American companies, Sony was one of a new crop that was almost entirely Japanese — think Canon, Nikon, Panasonic, Fujifilm and Olympus.

For consumers, digital cameras had one critical advantage. Following the launch of the Apple Macintosh in 1984 and the World Wide Web a few years later, computers were moving into the household. Home computers created new ways to store and share images at scale. Film cameras and instant cameras were analogue, and could not leverage this growing ecosystem. But digital cameras plugged right in, and this fueled their explosive growth into the new millennium.

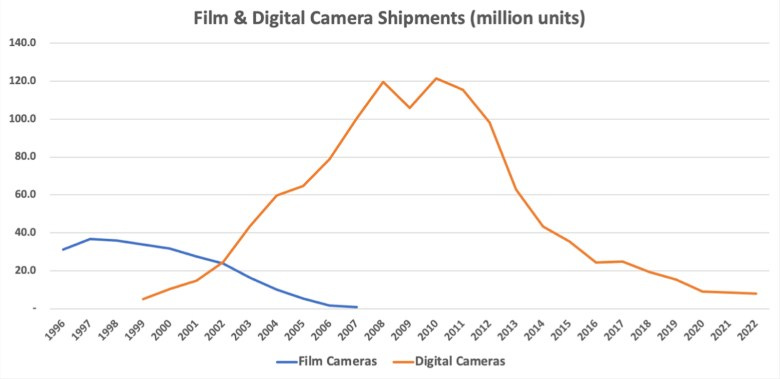

Digital cameras became practically the only cameras that mattered. Film cameras did not die completely, and remain available today. But the vast majority of films, tv shows and photographs, both consumer and commercial, were shot with digital devices. A new generation of artists emerged powered by tools that were cheaper, easier to use and offered capabilities once only available to large organisations.

So began the unravelling of two of America’s most beloved companies. Polaroid filed for bankruptcy in 2001, and Kodak in 2012. In parallel, Sony was ascendent, expanding into new markets to become one of the world’s most powerful companies. The changing of the guard was complete — film to digital, Polaroid to Sony, Land to Morita.

Consumerisation: Steve Jobs, Apple and iPhone domination

As digital cameras and home computers improved through the 90s, mobile phones were also crossing the chasm from archaic bricks to useful commodities. The first wave of companies, like Motorola and Nokia, made phones smaller and cheaper as mobile networks gradually got better.

Around 2000, phones acquired cameras. Sharp, of all companies, was first to market. For years, camera phones were a bit of a joke, and nobody took mobile photography seriously. Companies loved to highlight how many megapixels the camera had, despite tiny phone screens that made them largely pointless. Interoperability was challenging, and sending images via mobile networks was extortionately expensive.

These were the days when WAP meant Wireless Application Protocol, and many of you will remember them. Much like emerging AI devices, the industry was yet to converge on a mobile form factor, and it felt something like Darwin’s endless forms most beautiful.

For years, commentators had speculated about when Apple would make their entrance. Steve Jobs had returned to Apple in 1997 after a turbulent decade, and sentiment was picking up, especially following the success of the iPod. It seemed like it was only a matter of time.

Jobs idolised Edwin Land and Akio Morita as well as their companies. In fact, much of Apple’s product philosophy could be seen as a continuation of Polaroid’s own philosophies. Jobs’ focus on intuition over customer research, fusion of science and the humanities and violent allergy to copycat products are all traceable to Land (and to some degree, Akio Morita).

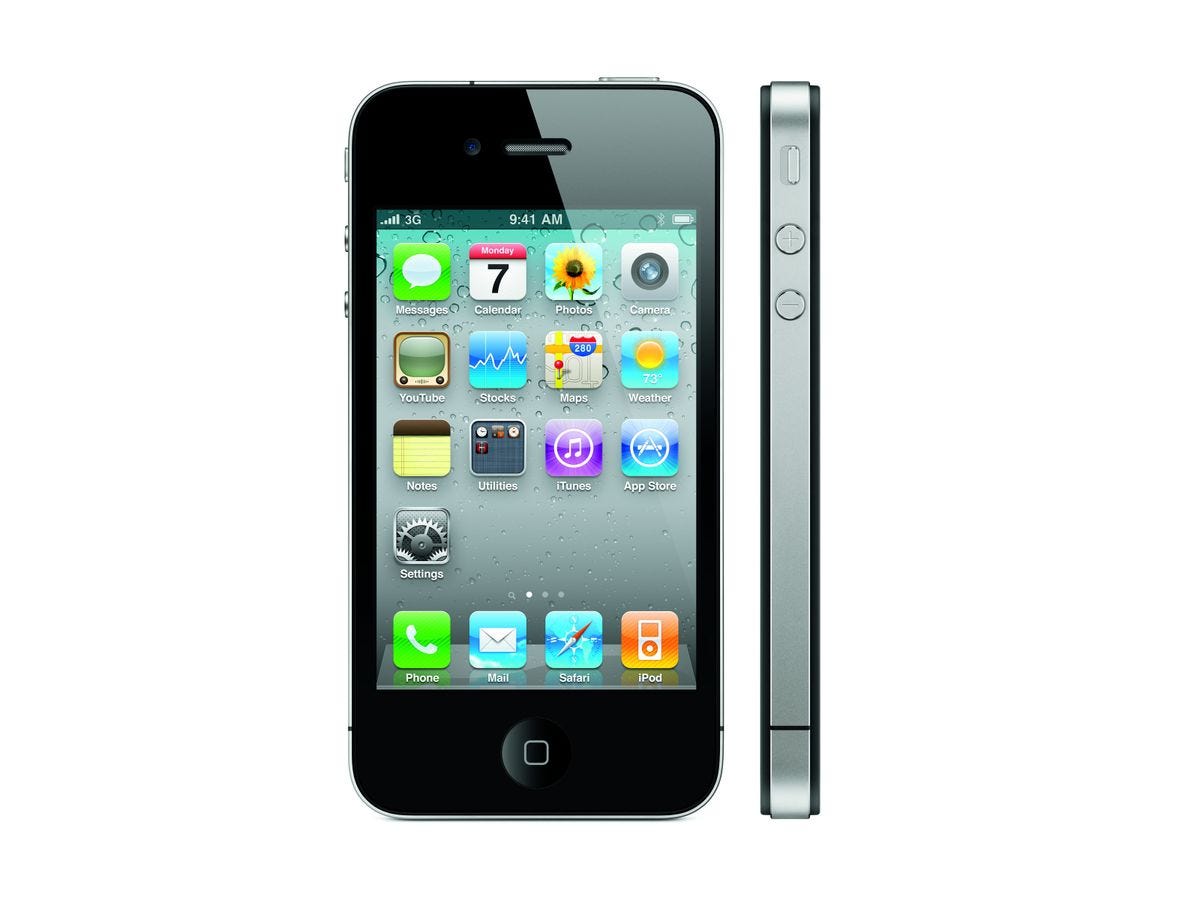

Fitting, then, that Jobs would become the one to realise Land’s original vision of a point and shoot camera that lived in your pocket. The iPhone was announced in 2007, though the camera barely featured in Jobs’ presentation. Most smartphones had cameras, and Jobs recognised that the camera was not what made first iPhone special, nor did customers care how many megapixels it had.

What Jobs understood and demonstrated throughout his Apple career was that it wasn’t just about the technology. It was about how customers interfaced with the technology. iPhone was perhaps the purest example, replacing buttons galore with a simple touchscreen.

The most advanced phones are called smart phones, so they say. And the problem is that they’re not so smart and they’re not so easy to use… Well, we don’t want to do either one of these things. What we want to do is make a leapfrog product that is way smarter than any mobile device has ever been and super-easy to use. This is what iPhone is. — Steve Jobs

It took some time for the iPhone to diffuse. The domination regime began around 2010 with the release of the iPhone 4. Despite early issues with the antenna, this was the release that refined the form factor. It remains one of the all-time great product designs. After a decade-long Cambrian explosion, the industry began to converge and other device manufacturers followed Apple’s lead.

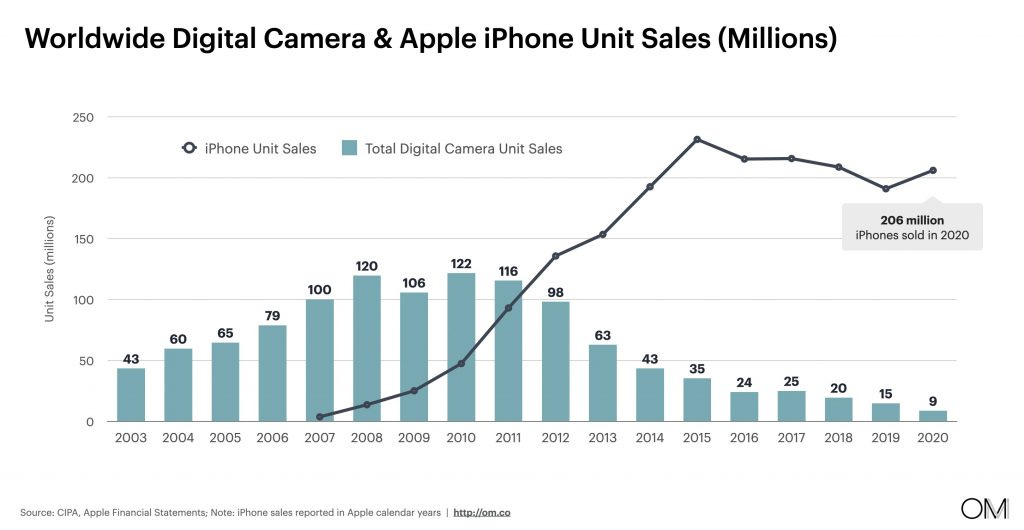

The iPhone’s impact on photography was not obvious looking forwards, but it is very clear looking back. Smartphones were expensive, and it became increasingly difficult to justify not having one after about 2010. Most came with a powerful camera and a good screen for viewing photos. For most people, it didn’t make sense to have a digital camera as well. Smartphones took on the role of point and shoot camera, and this was enough for the vast majority of consumers.

Of course, it wasn’t just about the camera. Around the time of the iPhone 4 release, iOS developers were beginning to understand the mobile paradigm and the app store was seeing useful apps. Like computers had done in the 90s, apps made it an order of magnitude easier to share photos on the internet. Where the original photo sharing apps, like Flickr, had been limited by the adoption of hardware and the simplicity of uploading photos, apps had no such limitations. Social media apps like Facebook (released 2008) and Instagram (released 2010) took off like rocketships, with photo sharing at their core.

For Sony and the other digital camera manufacturers, of course, this was all bad news. The new generation had arrived. Sales peaked in 2010 and over the next decade, declined precipitously back to 1990s levels. Today, the cameras in the latest iPhones are so good that it is increasingly hard to make a case for a standalone device. So while digital cameras remain a crucial component of professional work across the film and photography industries, on the consumer side all but the hipsters have switched to smartphones.

Ironically, smartphone marketing has now recentred around the camera. We’re back to comparing the size of our pics. Photography ended up being one of the killer features, as Land had predicted all those years ago.

As if by clockwork, apps raised concerns once more about what photography had become. Critics argued that filters enabled social media users to exaggerate themselves and their lifestyles. Artists decried the blobbification of the art form and the loss of authenticity. Professionals lamented the good old days when people were forced to hire photographers. These remain current debates even today.

But like before, none of this actually mattered. iPhones became ubiquitous, selling almost 2.5 billion units to date. Photo sharing became ubiquitous, with Facebook reaching 3 billion users and Instagram reaching 1.4 billion. Together, they brought a new generation of amateurs finally able to take great photographs with no effort. Some might question the emergence of a new ‘art’, but those questions are largely semantic — smartphones enabled new creative possibilities and new ways to share them. And where there is creativity, there is art.

Ultimately, the world adapted to the new paradigm and almost 200 years after the first cameras, photography completed its transition from frontier technology to boring ubiquity.

Oh it has a camera? Whoopty-f*cking-doo grandpa. — Anonymous 12 year old

Back to the future

And so here we are, in the present day. Another new generation is arriving — this time, photography is no longer about shooting. Now, it is about generating. As will become true across the arts. The shape of the future is looming into view and once more we are hearing the cries. Once more we are feeling the shift. Once more we are being told that new technology is bringing art’s inevitable conclusion.

I am utterly disgusted. If you really want to make creepy stuff, you can go ahead and do it, but I would never wish to incorporate this technology into my work at all. I strongly feel that this is an insult to life itself. — Hiyao Miyazaki

So many people in the AI industry think they have a right to steal the entire corpus of human creative output - in writing, music, art, everything - just to feed their machine intelligences that aim to render all human writers, musicians, & artists unemployed & obsolete. — Geoffrey Miller

David Senra at Founders Podcast likes to say that “history doesn’t repeat itself, human nature does”. If there is one thing to take away, then this is it. But what is relevant here? What can we learn from the history of photography and what can we expect to repeat?

Well, the new thing usually starts out looking like a toy, and few take it seriously. Once upon a time, Polaroid was just a way to take sexy selfies. Camera phones were just a way to compare megapixels. There is a dogma that the current thing has some essential nature that is irreplaceable. Incumbents rest on a false sense of security, believing that the current way is the only way.

But often, the toy uncovers an entirely new market by making something that used to be difficult become simple. Sometimes, that market is much bigger than the one it evolved from, because its newfound simplicity enables a much larger generation of customers to participate. This only becomes obvious after the fact.

Companies that made their name doing it the old way mistake the bad early versions for a bad future product. By the time they realise, it is already too late and they are outmanoeuvred by nimbler companies whose expertise is built on the new way of doing things. Standing on the shoulders of fallen giants, these companies go on to reach heights that were unreachable for prior generations.

Meanwhile, a professional class who have built a career on the old generation of tools see the new tools as a threat. They see people who use them as unworthy, lacking the refined taste they invested years to acquire. They buck, moan and declare the end of times — that art is losing its essence and future generations be damned. They use every means at their disposal to discredit the new way, to ban it and to hide from what, deep down, they know is coming.

But the new entrants continue unperturbed. Because they don’t care what the professional class thinks. Because ultimately, they just want to make cool stuff. And when a new technology suddenly makes that possible, those who could not afford it or affect it before seize the opportunity with both hands.

In each generation, previously manual tasks get automated. But not everything gets automated — there is always a variance in the quality of the results. Some people are just better at it than others, and those people emerge as a new generation of artists. New artists using new tools expands the space of possibility.

It’s not just about the artists. Automation reduces the barrier to entry and enables amateurs to become more like the professionals used to be. It raises the floor and the ceiling, and the discipline becomes exponentially richer and more interesting.

Once you see it, you realise that we are living through the same old story. It’s a story of creative destruction; a sheep in wolf clothing. And it’s not just about photography — substitute any kind of media, even any kind of technology, and you can draw essentially the same conclusions. It’s almost boring.

The only difference is that it is happening faster this time. It took 3 decades for instant photography to mature. It took 2 decades for digital photography to take off. 60 years after the first instant camera, it took smartphones just 1 decade to finally crack Land’s original vision. This time, it won’t be measured in decades.

Of course, I cannot say exactly what will happen. The names and faces are going to be different this time. But like it has done many times in the past, a revolutionary new capability will create new markets and mint new artists that tools of the past could never serve. If history is anything to go by, the losers will be those who stick their head in the sand, failing to grasp the future before the last petal falls.

And so here is the message:

To all the artists and founders out there who are using AI, unperturbed as your heroes chastise your work as the devil — lean in, keep going and buckle up. It’s going to get worse before it gets better, as AI consumes the creative disciplines. Your time is coming and one day you will become the leaders. But remember what you’re living through, because eventually you will become the old generation and the cycle will repeat itself.

And to all the others — nobody cares what Kodak fanatics thought about instant photography. Nobody cares what film camera geeks thought about digital cameras. Nobody is going to care what you think about AI either. History tells the story of the winners, not the losers, and it is rarely kind to the Luddites. So rather than attacking the new tools and the people using them, pick them up and play with them. Your best move is to join the revolution, not to fight it, and the sooner you realise that, the better you will do.