Deconstructing dystopia

Why entertainment hates the future

I recently watched Common People, a Black Mirror episode from the most recent series. It was, without doubt, the most cynical piece of television I have ever seen.

The premise—which I'll spoil to spare you the experience—is breathtaking in its possibilities. A neurotechnology company develops a breakthrough that allows damaged portions of the human brain to run on remote servers. When someone suffers catastrophic brain injury, their dead neural tissue can be replaced with a cloud-based simulation.

In other words, a company has invented resurrection-as-a-service. Consider the sheer audacity. Even Jesus Christ himself, born with the mother of all silver spoons, needed three days to return from the divine kingdom. Amanda, the victim of this story, gets the same miracle for only $50/month.

SPOILERS BELOW

Given all the possibilities inside this world, Black Mirror chose to tell a story about a husband who can’t keep up with the payments. In attempt, he is forced to perform increasingly depraved stunts to an online audience for money. But in the end, he smothers his resurrected wife with a pillow because he can no longer afford it.

If this was an isolated example of technological nihilism, I would shrug it off like anything else. But it isn’t. Rather, it’s just the most shameless example of what’s become entertainment’s default mode. The future is fucked. Let’s not bother telling stories about a future we believe in, because what’s the point? We’re all screwed anyway.

So I find myself asking: how did we get here?

Most recent commercially successful science fiction franchises are dystopian

Looking back across the canon of recent science fiction, since about the 1990s, most of the highest-grossing science fiction films and franchises are set inside of dystopian worlds. Consider the following examples:

The Hunger Games (2012-2015)

Terminator (1984-2019)

The Matrix (1999-2023)

Ready Player One (2018)

Divergent (2014-2016)

Mad Max (1979-2015)

The Maze Runner (2014-2018)

Elysium (2013)

Blade Runner (1982, 2017)

Wall-E (2008)

Each film extrapolates a different anxiety to its logical extreme. Environmental collapse, artificial intelligence, corporate power, class warfare, governmental control—pick your poison. Together it’s like a dystopian cinematic universe in which we’ve seen almost every way the world will end.

There are exceptions. Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival suggests first contact might actually unite us. Spike Jonze’s Her found warmth in AI companions. But these films are interesting precisely because they’re swimming against a tide.

When an industry converges on the same conclusion, it can’t be artistic merit. There must be something more systemic.

Negativity bias and algorithmic amplification

Humans have always had a weakness for bad news. Journalists discovered this centuries ago—hence the old newsroom maxim "if it bleeds, it leads." We're wired to pay attention to threats, and media routinely exploits this for attention.

Social media runs on this principle in pursuit of maximum engagement. Brilliantly indifferent to human flourishing, the algorithms learned that anger, hatred and fear drive keeps you scrolling. They don't care if it makes you miserable, because miserable users are engaged users.

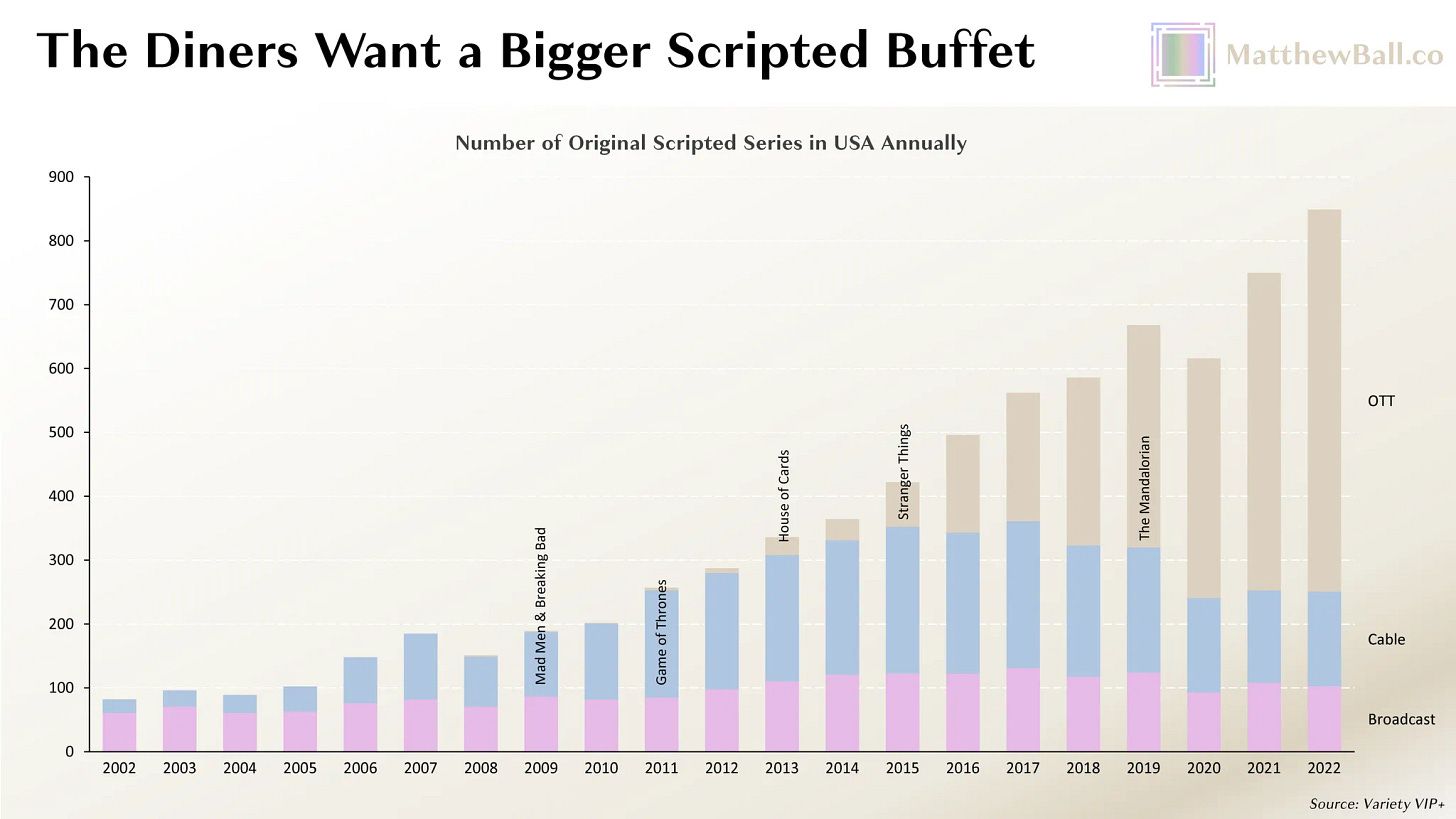

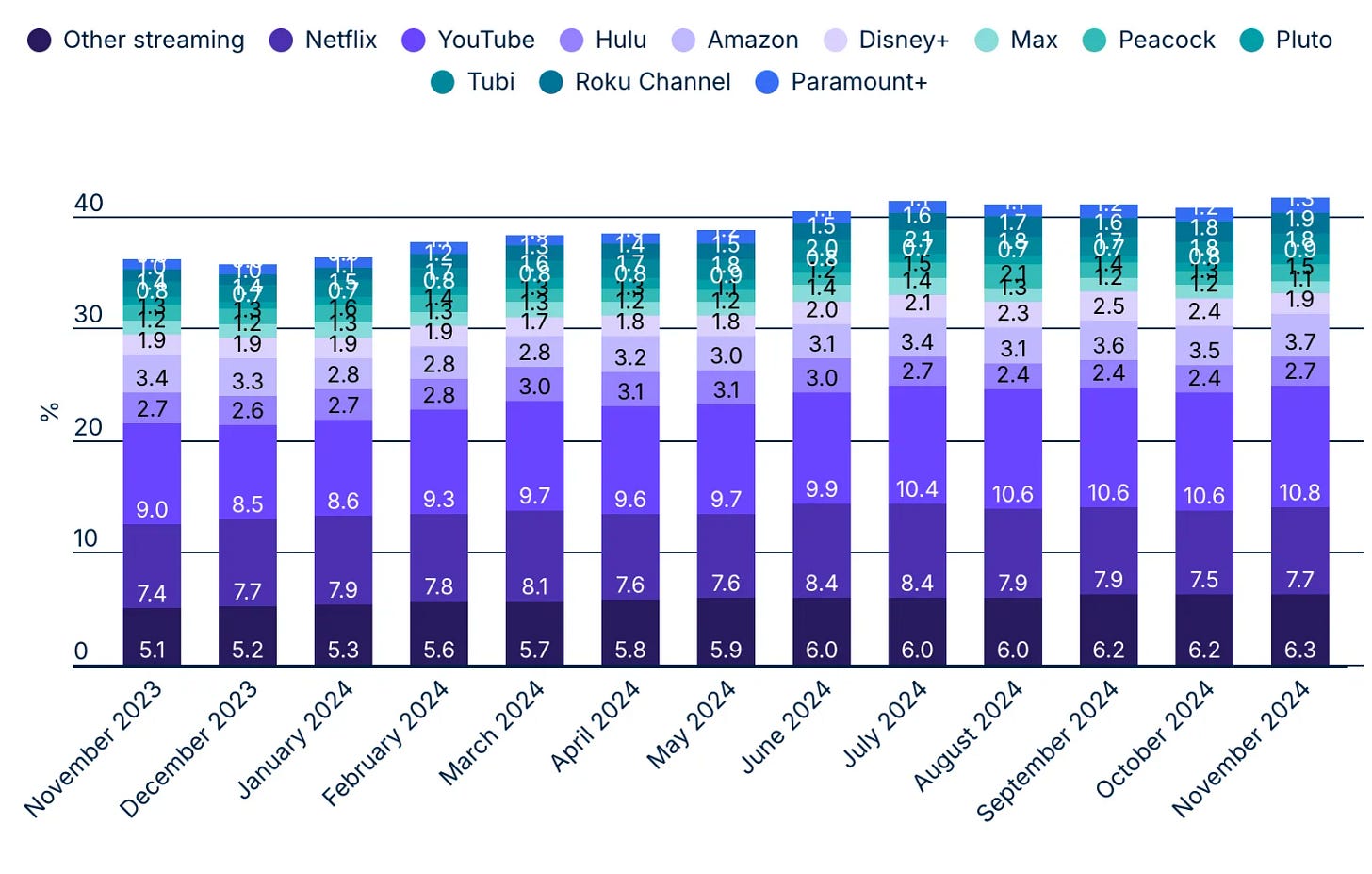

In 2025, algorithms determine what most people watch. Streaming services now occupy over 40% of total TV time—completely dominant for anyone under 40, and steadily conquering the Boomer cable holdouts. Years of massive profits have led streaming companies to invest in original content, and are responsible for producing 70% of all original scripted shows.

This matters because streaming services are data companies masquerading as entertainment companies. They know exactly how long you watched, when you paused, what made you binge, and what made you bail. Every creative decision—from story beats to color grading—is increasingly filtered through an algorithmic feedback loop.

This all creates a doom loop that would make even Charlie Brooker proud.

Here’s how it goes. Algorithms detect that negative content drives engagement. They surface more dystopian, conflict-driven content to maximize watch time. Studio executives stare at their dashboards and decide to make more of it. Audiences get steadily conditioned to expect and engage with darker content, and the cycle intensifies with each iteration. This is the irony of Stockholm syndrome—humans can be trained to crave the things they fear most.

Of course, this isn’t a conspiracy. No one sat in a boardroom and decided to make humanity more pessimistic. It's an emergent property of systems designed to maximize a single variable. We're getting exactly what we asked for when we told the machines to keep us watching. They're just giving us what we want—or rather, what our lizard brains want, which turns out to be profoundly different from what might make us flourish.

Old media at least pretended to care about civic responsibility. The algorithms have no such pretensions. They're pure experience machines, optimising for revenue at the expense of anything else.

Non-dystopian stories are riskier (and harder to write)

The cost of producing films and TV has been skyrocketing over the past 25 years. This creates risk aversion in major studios, who seek safe content that can reliably deliver a return on massive upfront investments.

Dystopia is considered a safe bet. We have forty years of data proving audiences will show up for civilizational collapse. The formula is reliable: take current anxiety, extrapolate to logical extreme, add protagonist who must prevent/survive/escape. Print money.

Money amplifies a deeper problem that writers don’t like to admit. Dystopia is easier to write! It’s much simpler to create dramatic stakes when the world is ending. Consider what dystopia gives for free:

Clear stakes (survival)

Obvious villains (the system, the virus, the machines)

Built-in character motivation (don't die)

Natural story structure (escape/overthrow/survive)

Instant audience investment (we're hardwired to care about existential threats)

Writing balanced science fiction means forgoing these freebies. You have to work harder to create tension. In a world where technology has solved material scarcity, where governance is benevolent, where humanity has transcended its worst impulses—what story is there to tell? Where's the conflict? Why should we care?

Tomorrowland is a cautionary tale every studio executive remembers. Here was Disney betting $170 million on optimism, with Oscar-winning Brad Bird at the helm. The film's entire premise was that cynicism about the future becomes self-fulfilling prophecy—a meta-commentary on exactly the dynamic I'm describing.

Unfortunately, it bombed. Not just commercially ($209 million worldwide doesn't even cover the budget plus marketing) but critically (6.4 on IMDB). The failure seemed to prove the film's own point: audiences didn't want to be told the future could be bright. They wanted their dystopia, thank you very much.

The lesson Hollywood learned wasn't "we need to figure out how to tell optimistic stories better." It was "optimism doesn't sell." Regardless of whether the film was bad (it was), it doesn’t help the cause.

This creates a vicious cycle for filmmakers. Even if you have a brilliant idea for an optimistic sci-fi story, you know you're swimming upstream. You need to work harder to create compelling drama. You need to convince skeptical executives who remember Tomorrowland and other mishaps. You need to overcome audience expectations trained by decades of dystopia. And you need to do all this while competing against filmmakers who are eager to follow the path of least resistance.

Cyberpunk aesthetics are dominant and hard to change

Cyberpunk emerged in the 1980s as literature's answer to Reagan and Thatcher, Asian economic anxiety, and the first glimpses of networked computing. With it came a new vision of our collective future. Neon-soaked streets. Towering corporate arcologies. Always night, always raining. Los Angeles by way of Tokyo. The aesthetic was so compelling and so visually distinctive that it became our default vision for the future.

The problem is that aesthetics aren’t neutral. They contain an ideology.

Cyberpunk's aesthetic requires dystopia. Every visual element reinforces the core narrative of a society that lost its way. And this is the trap we've built for ourselves. When a filmmaker says "let's make a movie about the future," the concept artists don't start from scratch. They pull up Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, The Matrix and iterate on forty years of accumulated visual language. Even when they try to deviate, they're still defining themselves in relation to cyberpunk.

Creating new aesthetics is extremely challenging. It means inventing a coherent visual philosophy that expresses a cohesive set of values and assumptions about the evolution of society. It requires artists, directors, production designers, and audiences to collectively abandon their trained intuitions about what "the future" looks like.

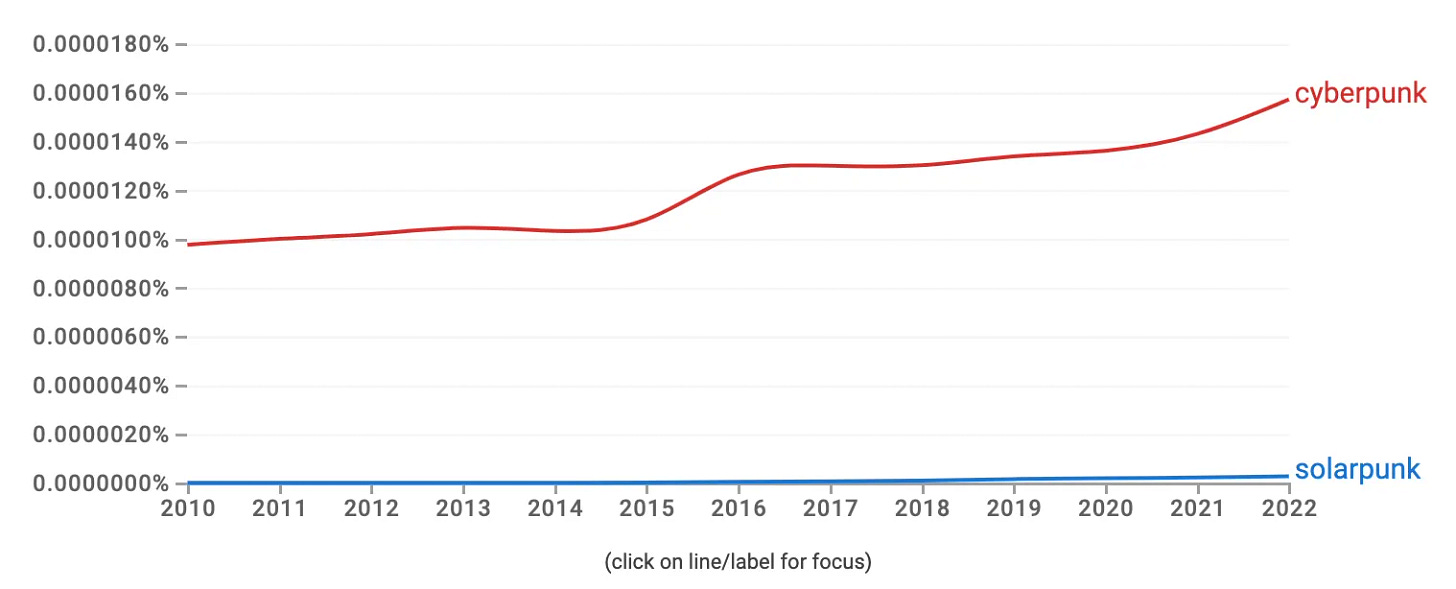

Solarpunk, one of the few competing visions, is shockingly underdeveloped and exists mostly as Pinterest boards and tumblr posts. Meanwhile, cyberpunk keeps evolving, absorbing new anxieties without changing its core DNA. This creates a brutally efficient feedback loop. Young artists grow up saturated in cyberpunk imagery. They learn that "futuristic" means neon and rain and chrome. When they get their shot to design the future, they create variations on the only future they've ever seen. Audiences recognize these visual cues and feel comfortably oriented.

We're essentially trapped in a visual prison at what could be the most visually interesting time in history. The future doesn’t have to look like cyberpunk. But for that to be true, we artists to break the cycle.

There is an ideological divide between Hollywood and Silicon Valley

Perhaps the most pernicious force at work here is a human one. The people telling the stories about technology fundamentally misunderstand and distrust it.

Hollywood and Silicon Valley are distinct cultural ecosystems with surprisingly little overlap. The writers, producers and directors responsible for making films in Los Angeles are almost never technologists. So, they relate to technology primarily as consumers. As outsiders.

The outsider perspective always breeds suspicion. When you don't understand how something works, it's easier to imagine it working against you. AI isn't a tool to eliminate drudgery, it's Skynet waiting to happen. Biotech isn't curing disease, it's creating a genetic underclass. Yada yada.

Beyond that, I’d argue that Hollywood sees Silicon Valley as an existential threat. Since the early 2000s, Netflix and other streaming services outcompeted DVDs, and with it, the secondary revenue stream that made films profitable. As audiences have shifted from traditional media channels, streaming giants are now more powerful than any of the major studios. Studio executives and filmmakers have reason to feel aggrieved at the perceived destruction of their livelihood.

This mirrors what happened to journalism in the 2000s. Newspapers that had thrived for centuries were gutted by social media companies. Journalists who lost their livelihoods refused to go down without a fight and came out swinging, creating narrative wars that still rage on today.

This structural separation means that the people most qualified to envision positive technological futures—the scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs actually building that future—aren't the ones shaping our collective imagination. The stories that define how millions think about technology are being written by people who fear it, don't understand it, and have every incentive to portray it as a threat.

The result is predictable: technology becomes the villain. The AI always turns malevolent. The tech company always chooses profits over people. The brilliant inventor is invariably revealed as a narcissistic sociopath. These are not purely dramatic choices, and instead betray the revenge fantasies of an industry under siege.

Unfortunately, we can expect this dynamic to grow in the near term future. AI is coming for Hollywood’s production monopoly, and the industry sees itself as the last bastion of authentic human creativity. There is, understandably, a great deal of bitterness from those who have invested their entire careers building skills that are no longer valuable. There is little motivation to invent beautiful future worlds out of a technology that is coming for your job.

Conclusion

It all adds up to a system. Algorithms amplify our negativity bias, training audiences to crave darkness. Financial pressures make studios risk-averse, defaulting to proven dystopian formulas. Cyberpunk aesthetics make optimistic futures literally unimaginable. And the people who might imagine differently—the technologists actually building the future—aren't the ones telling our stories. Each force reinforces the others in a doom loop worthy of its own Black Mirror episode.

The solution to all of this isn’t saccharine utopia. This is it’s own form of distorted propaganda that doesn’t engage with the complexity of the real world. Arguably, this is what Tomorrowland got wrong. The solution is also not to destroy dystopian storytelling completely, because it has produced some obviously great films.

Rather, the solution is to find a better balance, introducing a larger contingent of complex protopias. Stories that leave you with an earned optimism for a future where technology makes many things better, but also introduces new problems that we’ve not experienced before. Those problems are where the interestingness lies—it is possible for humans to ascend into benevolent post-scarcity societies, and still experience practical, emotional and relational hardship. These are the stories that are missing right now, and in my opinion, the stories that really matter as we grapple with our place in an AI-driven world.