Imagine aliens landing on Earth. “Why are you here?” is the first question that springs to mind. But aliens probably don’t speak English, and so that’s easier said than done.

First, we would have to establish a way to communicate. This is the plot of Arrival, one of the best science fiction films of the last few years. Louise, the film’s main character, is a linguist and communications expert who is chosen as part of the mission to communicate with an alien Heptapod race. Her strategy is to translate between languages, so that the aliens have a basic understanding of English, and the humans have a basic understanding of Heptapod.

[SPOILER WARNING]

The film explores the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which suggests that language determines how we think. This is in some sense obviously true. Language is a medium, and it constrains thought as all mediums do.

English has two important features — it directly represents sounds, and is bound by linear time since words follow sequentially. As Louise learns to translate Heptapod, she discovers that neither of these things hold true. The written language, by separating itself from speech, exists outside of linear time. A ‘logogram’ (roughly a sentence or paragraph) communicates a whole simultaneously.

The alien language of the heptapods, on the other hand, is nonlinear, written in circular puffs of smoke with no beginning or end. The entirety of the thought or sentiment is experienced and communicated at once, not in a progressive order. A logogram, therefore, is free of time.

The idea of the film is that English forces us to experience time linearly. But Heptapod is free from that constraint, enabling the Heptapods to perceive time non-linearly. Non-linear time means that the future already ‘exists’, and it can loop back around to cause itself to happen. Cause and effect becomes chicken and egg — did the cause produce the effect, or did the effect produce the cause?

Heptapod is a fascinating idea. It’s fiction, of course, but it hints at something real that is happening all around us. That thing is hyperstition — the idea that our stories of the future loop around to make themselves true.

Hyperstition is a feedback loop in time

The space of possible futures is very large. Think of it as a garden of forking paths spreading out in every direction — for people, technologies, societies, planets and galaxies. It’s too big to comprehend directly, but imagination is a way to explore some of it. It enables us to use what we know about the past to think about what might happen in the future.

We have a limited ability to predict the future — that is, to select the “right” path from the space of possible paths. We might be able to predict 1 year out, or even 10 years out. But as you go further into the future, it gets harder to predict what will happen.

Over a longer time horizon, like 100 years, perhaps there is a probability distribution over all possible outcomes. But if there is, we can’t see it. In any case, so many things can change between now and then — many of which are beyond our current comprehension — that “probability” seems like the wrong tool. We simply don’t know.

Just because we can’t predict the outcome, doesn’t mean we can’t influence it. Influencing outcomes is the realm of hyperstition. The idea is to start at the end, and tell stories about the future that inspire people in the present to help make them real.

Superstitions are merely false beliefs, but hyperstitions – by their very existence as ideas – function causally to bring about their own reality. — Nick Land

Hyperstition seems esoteric, but I think it’s fundamental. The future is too complex for us to comprehend, and past a certain point, the best way to understand it is to tell stories about it. Stories create a shared model of the future that reduces uncertainty for something that is otherwise hard to think about. In turn, they create beliefs that enable people to take meaningful actions in the present.

This creates a feedback loop between future and past. Stories about the future drive actions in the present. In some sense, stories move the future towards the present, and actions move the present towards the future. The result is that whatever the “actual” probability of the eventual outcome, the story works to increase (or decrease) it.

Stories are not supposed to be exactly “correct”. By aiming for a “point”, the idea is that we are more likely to hit an “area”.

The feedback loop means that the story often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Groups of people believe it to be true, and coordinate their actions in a way that causes it to become true. Technologies, aesthetics, belief structures, values, personalities and organisations can be born this way, having originally started as fictions.

The strange thing about hyperstition is that from the point of view of the past, it could have gone many ways. No story about the future is ever “true” looking forwards, but it becomes true looking backwards. Similar to Heptapod, the future loops around to cause itself to happen by acting on the past. Weird.

[fiction] operates not as a passive representation but as an active agent of transformation and a gateway through which entities can emerge. — CCRU

Hyperstition rules everything around us

Hyperstition is an intuition for understanding some of the strange forces that cause things to happen around us. Why do people do what they do? How do we pick problems to work on? How do we decide how to use life? The future is always uncertain, and the world is made of fictions that attempt to reason about it. Stories are within us and around us at all times, influencing how we think about the future and the actions we take in the present.

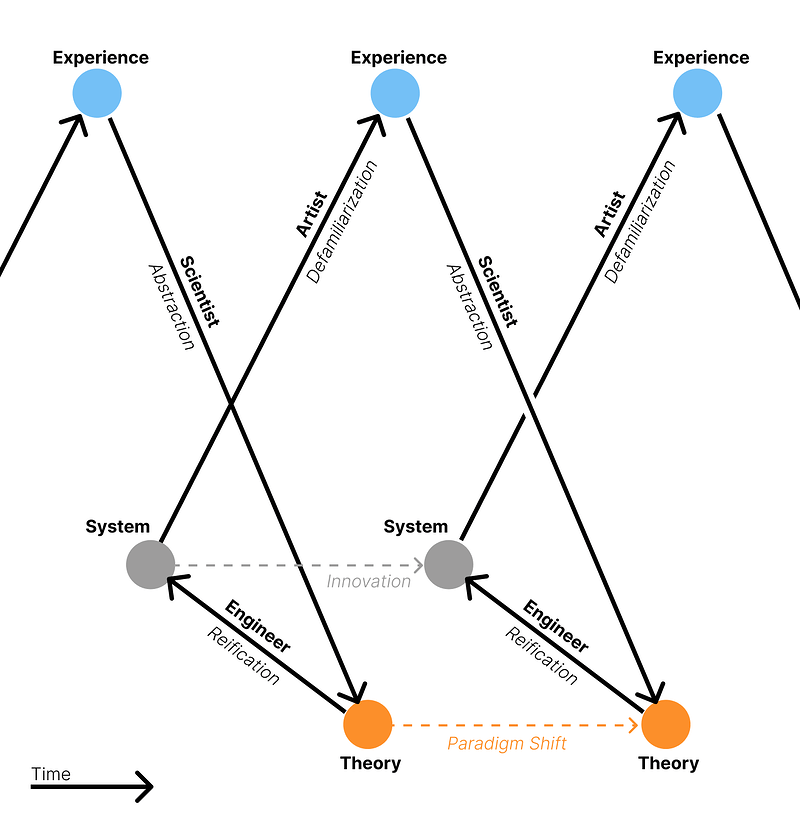

I often think about this in the context of art, science and technology. Together, they are responsible for moving things forward — they help us to explore the space of possible futures, opening up areas we haven’t seen before. Hyperstitional fiction is a medium which enables them to influence and feed back on each other, driving change in societies.

Often, art gets there first. Books, films and games are mediums through which we can explore possible futures without the constraints of present science or engineering capabilities. Stories push us to imagine futures we haven’t thought of before, and project what it might be like to live in them. We can then work backwards to determine what needs to happen for the story to become a reality.

For example, science fiction explored interstellar civilisation before we have the technology to implement it. Through it, we foresaw problems like time dilation, energy production, lightspeed propulsion and interstellar habitation. We imagined space habitats, starship fleets, Dyson spheres, O’Neill cylinders, cryopreservation and many other systems as possible solutions.

Science takes cues from art. It pushes scientists to think about new ideaspaces. In the case of interstellar civilisation, fiction expanded the imagination of a generation of scientists who asked new questions about the nature of space and our ability to live in it. In some cases, it directly created new research directions.

Science has its own nested form of hyperstition. It often begins with a hypothesis, which is a falsifiable story about a future theory. It’s a way to start at the end and work backwards to explain a present phenomena. Hypotheses pull science along in places where the facts don’t exist yet, encouraging actions that prove or disprove them.

…despite one's sense of departing ever further from one's origin, one winds up, to one's shock, exactly where one had started out. In short, a strange loop is a paradoxical level-crossing feedback loop. — Douglas Hofstadter

Art also influences engineering. Science fiction is a great place to find startup ideas — it feeds back on entrepreneurs who are inspired to make fictions come true. So, the built world (and the digital world) comes to look as it was described in fiction. Meanwhile, company visions are a nested form of hyperstition that tell the story of a future product or service, enabling a group to coordinate work to make it a reality.

In turn, engineering and science feed back on art, encouraging it to be more ambitious in the search for novelty. Stories are a way to continuously bootstrap realities.

Hyperstition works because fiction makes the future (especially the “far” future) comprehensible when it is otherwise impossibly complex. It sets our expectations, and those expectations are constantly bending around to cause themselves. It is powerful because it gives us some influence over long-term outcomes beyond our direct control.

Hyperstition has always been there, but new kinds of media have made it more powerful. Word of mouth, print media, television and social media are increasingly powerful ways to distribute ideas. The feedback loops are now so complex that it is happening everywhere, all the time, in ways that are almost impossible to track. All we know is that when enough people believe, the world tends towards what we imagined.

AI supports hyperstition by amplifying training data

Hyperstition has come into popular focus recently because AI provides a new and more powerful mechanism.

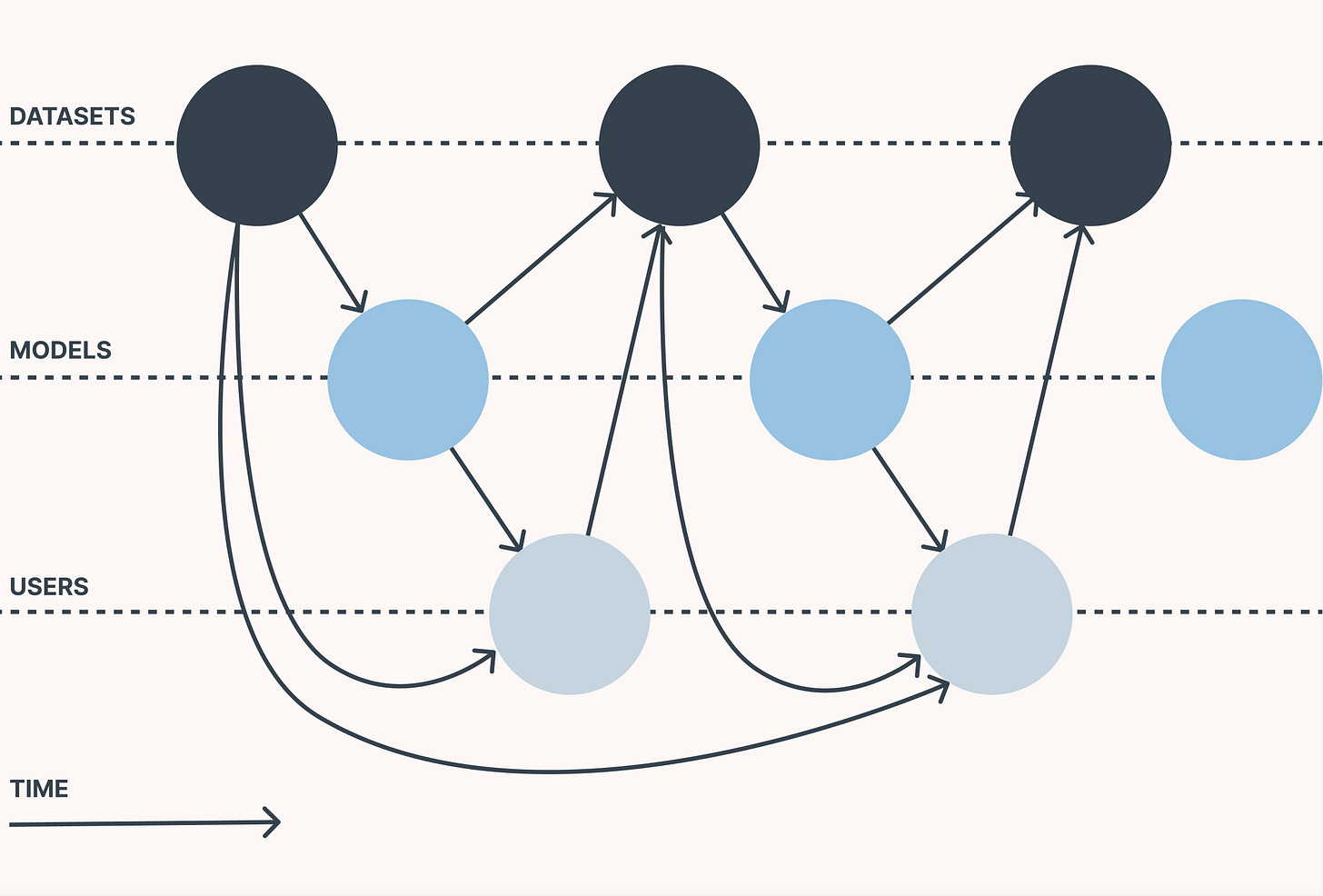

The idea of generative AI is to learn a function that approximates a dataset, and use it to produce new things that look like the dataset. In this current generation, what really matters is the dataset and the scale of the model. As the model gets bigger, it gets better at representing the dataset.

…trained on the same dataset for long enough, pretty much every model with enough weights and training time converges to the same point… when you refer to “Lambda”, “ChatGPT”, “Bard”, or “Claude” then, it’s not the model weights that you are referring to. It’s the dataset. — James Betker

The important conclusion here is that models amplify whatever is in the dataset. In turn, dataset amplification feeds back on model users. We can see early evidence in delvegate — language models love unusual words like “delve”, and as people use models, “delve” is appearing more frequently.

The idea is that by controlling what goes in the dataset, we control what shows up in the world.

If you project into the future, models will master domains like video, music and 3D environments. Meanwhile, new hardware interfaces will make them easier to use and more tightly integrated into how we interact with the world. Over time, models will increasingly influence the actions we take.

Datasets, then, hold a lot of power. Today’s models influence the dataset used to train tomorrow’s models, via synthetic data and model-assisted human data. Tomorrow’s models will feed back on users to influence their decisions. If today’s model’s can be largely controlled by what goes in the dataset, then what we put in the dataset today influences what will show up in the world tomorrow.

Since the cycle is recursive, datasets today can influence outcomes a long way into the future. Earlier datasets have a greater cone of influence.

Perhaps you can see the link with hyperstition. Let’s imagine that you have identified an idea about the future that you want to spread. In the past, you would have to distribute it via word of mouth, print media or social media. Each gives you power to influence other people, and if they believe your idea, they will help make it real.

Models offer a more powerful mechanism. If you can find a way to overrepresent your idea in the dataset, then the model will do the work for you. It will influence its users in subtle but important ways that increase the chances of making the idea a reality. It works together with the other mediums to expand your cone of influence.

You may have seen Janus on Twitter and wondered what is going on. Roughly speaking, this is my smoothbrain interpretation of his work — he is attempting to apply this idea in practice. Janus sees a possible future explosion of diversity in intelligent beings, many of which will be artificial and beyond human-level intelligence. But there are many versions of this future that go badly for all involved. Our responsibility in the present is not only to ensure that this explosion takes place, but to ensure that it happens safely.

This is a story about the future that most people can’t see, or don’t take seriously. That either means an intelligence explosion is less likely to happen at all, or we are likely to get one of the bad versions. To get one of the good versions, a specific version of the story needs to be believed for people to take the actions required to make it real. So, Janus intends to use hyperstition to increase the chances.

Janus' tweets are a kind of performance art that force you to think more expansively about the nature of LLMs as an intelligence. They are something very different from us — a kind of possibility space explorer or imagination engine that sees all possible futures in language. The core idea is that rather than trying to “fix” their inherent flaws (like low agency, schizophrenia etc) to make them look more like human intelligence, we can “fix” their flaws by pairing them with humans.

Tweets influence people’s worldview — some “get it”, and take actions that help it spread. As the group grows and produces downstream research, writing and other projects, it will influence the direction of the industry. In turn, this will influence future models, and those models will influence future people and future models in a recursive cycle that further spreads the worldview. Over time, the idea is to guide us along a path to a safe intelligence explosion.

…I am commencing a memetic landscaping project aimed at replanting the common folkway..

By communicating… concepts… designed for maximal viral spread, it is possible to make any idea famous…

…when someone holds a certain belief, [they] influence… downstream beliefs… By refactoring the current worldview, I am preserving… the worldview of future… people

[my goal is] forcing [a safe intelligence explosion] into existence… [my strategy is to] recreate myself as a memetic virus at scale…

— Janus (heavily edited for brevity)

Looking backwards, Janus is part of a nested hyperstition loop. Good first described the intelligence explosion in 1965. Von Neumann, Vinge, Kurzweil, Bostrom and Yudkowsky subsequently adapted it. The idea lives on, growing larger and more influential with every repetition.

The intelligence explosion was never “inevitable”. It’s inevitability is just a story because there are many possible futures. But the story has convinced enough people over time to condition actions in a recursive loop. We can’t yet say whether it will happen in reality. But if it’s physically possible, then the more people it convinces, the more likely it becomes.

At any moment, there are many people trying to hyperstition a future into reality. This has been the case forever — we’ve just got better at it over time. Now we have a more powerful mechanism.

Janus is (to my knowledge) the first person to deliberately use it. Janus knows that if he can get the word out now, then he can overrepresent his ideas in future people and future models. Recursive cycles of reinforcement can eventually establish his worldview as the historical truth, by ensuring that we select the path of a safe intelligence explosion from the space of all possible paths.

This mechanism will become more powerful over time. Future models will have agency, using their own “worldview” to explore possible futures and take actions towards them without human supervision. They will bootstrap their worldview from a “dataset” that includes our actions today and all of its downstream consequences.

This suggests that looking forwards, we can use hyperstition to condition the actions of humans and agents. We have a particularly great opportunity to steer the direction of the future today. Models are still in their infancy, and biasing the dataset now may represent the chance to influence all future intelligences. The idea of hyperstition is that technically, this has always been true — we’re just being more deliberate.

…whatever we teach AI now is going to steer the world very sharply in that direction in the years to come. Now is the "imprinting" moment where the baby duck learns to identify Mama. — Michael Garfield

Learning to Heptapod

Learning to hyperstition is something like learning to Heptapod.

If you learn it, when you really learn it, you begin to perceive time the way that they do. So you can see what's to come. But time, it isn't the same for them. It's non-linear.

I say this somewhat tongue-in-cheek. We can’t literally see the future, and the feedback loops are too complex to be controllable right now. Still, hyperstition suggests a kind of non-linearity that we can use as a deliberate force. Get really good at telling stories about the future, and you can bend them around to cause themselves.

![2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl 2001: A Space Odyssey (Original Soundtrack) - Limited Gatefold 180-Gram Vinyl [VINYL]: Amazon.co.uk: CDs & Vinyl](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!D9Ko!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5958746a-890c-44c6-b732-c67963c11fa6_894x894.jpeg)