Remember that scene from Interstellar, where Cooper falls into a black hole? There’s a useful analogy here in the context of emerging models.

To set the scene:

(TARS) Cooper? Come in, Cooper?

…

(Cooper) We survived.

(TARS) Somewhere. In their fifth dimension, they saved us.

(Cooper) Yeah? Well who the hell is they, and why would they want to help us?

Skip to 1:37 (end at 3:20). [SPOILER WARNING]

Looking around, we are confronted with a strange environment. “Sections” are connected by “strands”, extending infinitely in every direction. As Cooper reconciles the weirdness, TARS is first to recognise the situation.

They constructed this 3-dimensional space inside their 5-dimensional reality to allow you to understand it.

But what does it mean? TARS again:

Time is represented here as a physical dimension.

Slowly, realisation dawns. It’s not an environment. It’s an interface.

“They” have constructed an interface to time itself. It represents every moment and their relationships in time. Cooper:

Every moment — it’s infinitely complex. They have access to infinite time and space, but they’re not bound by anything.

“They” see it all at once. Every moment that has ever happened, perhaps every moment that will ever happen. They exist outside of linear time, and this interface collapses their experience into 3 dimensions.

Why, then, does Cooper find himself here?

(TARS) You’ve worked out that you can exert a force across spacetime.

(Cooper) Gravity? To send a message?

…

(TARS) They didn’t bring us here to change the past.

(Cooper) They didn’t bring us here at all. We brought ourselves.

Cooper’s epiphany is that “they” are future humans, using their understanding of the future to intervene in the past. But “they” don’t know which moment to choose. That’s why they need Cooper — he must use the interface to send a message to his daughter so that she might save the future.

They can’t find a specific place in time. They can’t communicate. That’s why I’m here.

Now, I’m not suggesting we take this literally. But it’s an interesting way to interpret the human-AI boundary.

Last week, I made the case that the big idea of generative models is that they represent (a subset of) possibility space directly. From the point of view of each token, language models see all possible next tokens, given what they learned from a dataset. They see possible ‘futures’ given ‘past’ context.

Successive token selections create a path through the tree of possibilities. For each generation, there could have been other choices, it just happens that this path was selected. Next time, the model will almost certainly choose a different one. When we use generative models, then, we are mapping possibility space.

The idea here is that the relationship between models and humans is like the relationship between “them” and Cooper.

Superintelligence : us :: “they” : Cooper

“They” experience a 5-dimensional reality that is beyond human comprehension directly. Similarly, models see a possibility space that is beyond human comprehension directly.

But “they” created a medium that made it comprehensible. Where Cooper had been seeing time linearly, the interface helped him see it from a different perspective and think new thoughts that didn’t belong in his previous model of reality. He saw that time is not linear, and forces could be exerted across spacetime. He realised that he could use these new ideas to influence the future by intervening in the past.

McLuhan was first to observe this property of media. It shapes how we think, and in turn, shapes the cultures that we build. Via the Gutenberg press, print media made science possible because it made scientific thought thinkable. In turn, an oral culture of stories, myths and rituals gave way to the enlightenment, through which we built a new visual culture based on rational thought.

Scientists start seeing something once they stop looking at nature and look exclusively and obsessively at prints and flat inscriptions. — Bruno Latour

We take this for granted today, because it is just what everyone does. But it had to be discovered, and it was discovered through a new medium that expanded our thinkable range. Perhaps the same is true looking forwards — new media can produce new forms of thought that are currently unthinkable.

Each representation allows us to think thoughts that we couldn't think before, and we continuously expand our thinkable territory. — Bret Victor

Generative models are a new medium for thought. Their unique capability is to make possibility space explicit. Superintelligent models are probably going to be really good at it. Rather than thinking of them as a way to replace human thought, we can take inspiration from Cooper’s tesseract to design interfaces that augment human thought with the capacity to comprehend possibility spaces.

Visualising latent space

Imagine landing in a foreign city. Your task is to find a specific location without using a map. Given enough time, you’ll probably find your way. But you almost certainly won’t take the fastest route, because you’re limited to what you can see in front of you. You’ll probably miss the most interesting detours, and worse, you’ll never know you missed them. You may even go round in circles because you can’t see where you’ve come from.

When navigating possibility spaces — art, science, life decisions etc — we experience similar problems. The top-down view is invisible to us, and we’re left to navigate using the immediate surroundings. Wrong turns and detours are common. We probably miss the most interesting locations, and never know we missed them.

For real environments, we invented maps because they enable a different kind of reasoning. By seeing how environments fit together, we can move around more efficiently and discover things we otherwise wouldn’t see. The internet (via GPS) makes maps even better, contextualising surroundings to our current location and browsing history.

Contextual maps open up a new dimension, encouraging users to look down on the space from a higher perspective. Using them, we can think new thoughts that don’t belong in the ground-level view. This is analogous to Interstellar’s tesseract, which revealed a “top-down” view of time enabling Cooper to see how it all fits together.

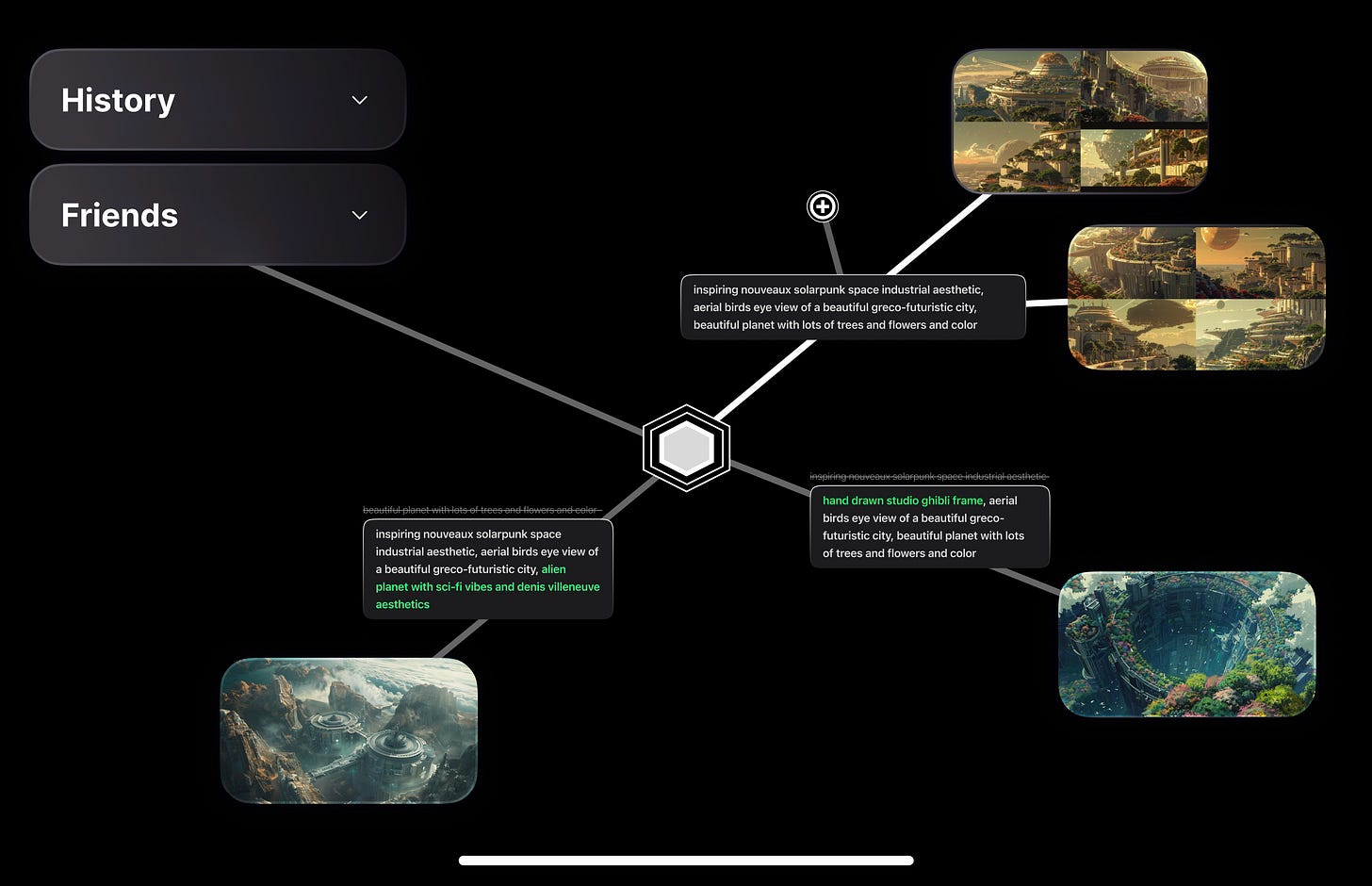

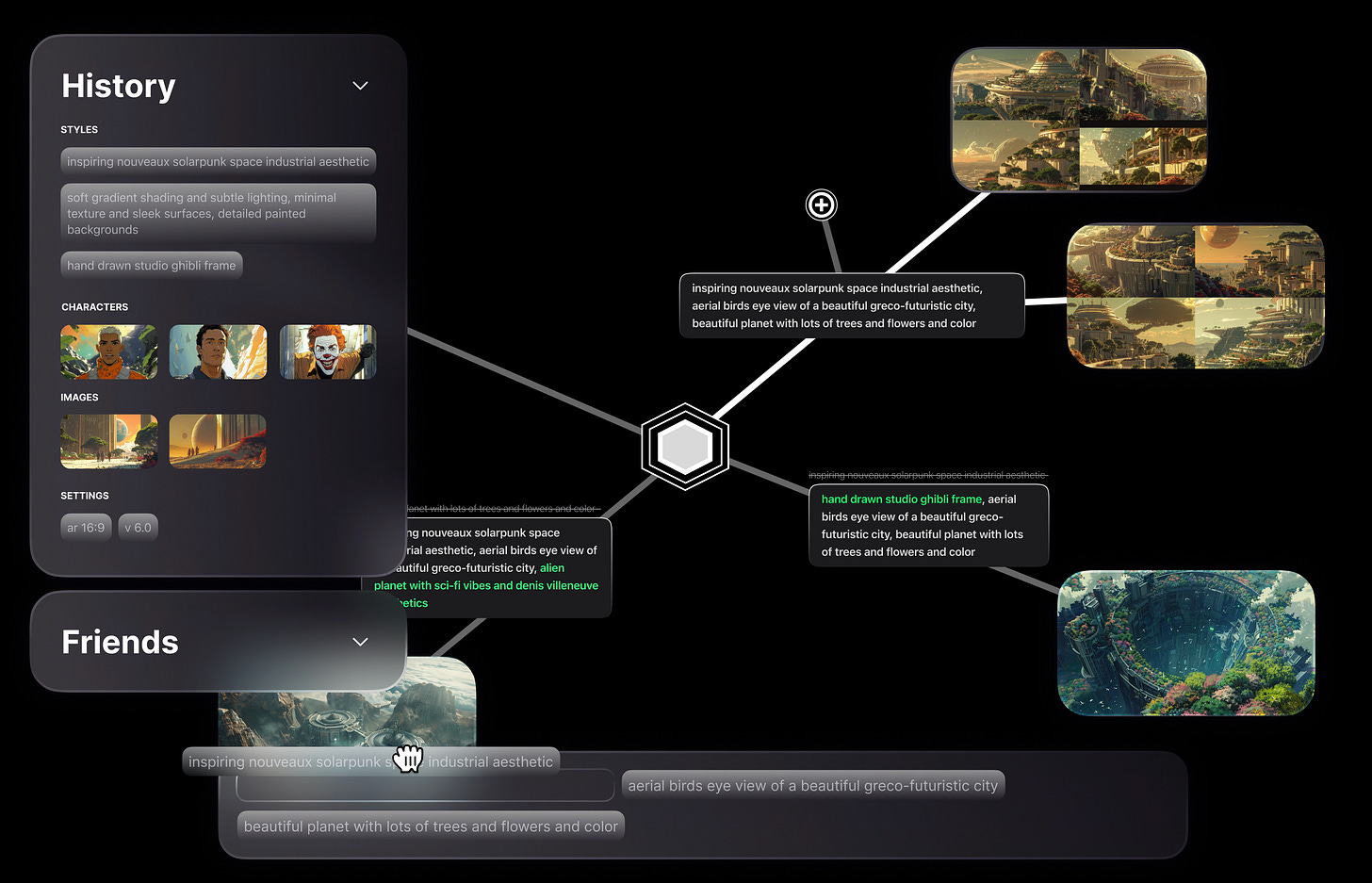

With generative models, navigation is about prompting. Prompting is something like the ‘ground level’ view of a city. It usually begins with a fuzzy idea of an image (“destination”) and it’s not clear how to reach it. Like exploring a new city, the best strategy is usually to just choose a direction and see where it leads. Gradually, you learn more about which prompts lead where and which areas are likely to be interesting.

The great step forward of generative models is that it makes the space accessible, even to those who are foreign. For example, most people can’t draw. But with Midjourney, suddenly everyone can. Midjourney makes (a subset of) the space of possible 2D images suddenly accessible to normal people. This is obviously great and a huge step forward.

But today, we are missing the map. We can’t see latent space from the top-down, and this limits our ability to reason about it. In most cases, we are probably missing the most interesting areas because we either don’t know they exist, or can’t reason about how to reach them.

Last week, I touched on Loom. Loom is interesting because it feels closer to an AI-native interface.

Loom’s core insight is that models enable recursive exploration of possibility space… Loom explores language models with threads that represent the tree of possibilities directly. Outputs build on each other and the idea is to prune the bad ones leaving only the most interesting… in the same way that a loom weaves threads into a cohesive garment, Loom weaves threads into a cohesive output.

Loom makes the journey through possibility space explicit, via a set of fundamental actions. From the perspective of any node, it’s forward, back, branch or prune.

This creates a few affordances.

Over many explorations, the tree structure is a representation of latent space (which can be thought of as the possibility space expressable by a model). It is a map. Loom represents it directly with a spatial interface.

The visual intuition hints at a different kind of reasoning. It’s a way to look down on latent space and see how the branches fit together.

If we took this insight more seriously, we can conceive of a new kind of interface built for generative models. A related visual intuition comes from Fez — a game consisting of environments and doorways.

Fez similarly maps environments using a visual tree. Like Google Maps does for real environments, it takes you out of the immediate surroundings and into a bird’s eye view. From any node, you see past and future routes through a different kind of reasoning. Rather than trying to remember where all the doorways lead, the map does the work for you.

Applied to latent spaces, maps would work together with prompting to provide an intuition for what’s possible, taking away a lot of the guesswork. They would enable you to “zoom out” to see the space, and reason about where you’ve come from and where you might go next.

In the forward direction, you can imagine augmenting maps with suggestive paths. This would include variations on the current prompt that encourage users to explore new directions they may not have thought of. Suggestions could come from multiple sources, including the users’ history of prior prompts, as well as other users’ histories that overlap with the current direction.

In Midjourney — for example — styles, characters or subjects used in the past could be reused as components in new generations. Similarly, when you arrive in an area of latent space that has been explored by another user before, branches could suggest new directions that recombine ideas from their context window.

The idea of maps is to make use of what the system knows about the model’s latent space to maximise the user’s imagination. Which is to say, it is about maximising the user’s capacity to comprehend the space of possibilities, in all of its branching complexity. The goal is to surface the user’s blind spots so that they can discover pathways they otherwise wouldn’t see.

Enabling non-linear thought

Seen this way, generative models are a direct unlock for non-linear thinking inside possibility space. The point of using them is not just that they “automate” the creation of something. It’s that this unlocks a higher level of imagination that enables you to see across whole possibility spaces. You can see all the possible directions and use this capability to eliminate the ones that don’t work.

Perhaps this seems abstract, but it’s a core part of how humans think everyday. We use past information to make predictions about the future, and use our predictions to make decisions in the present. In some sense, every decision is about selecting a path through the space of possibility, and so every decision is limited by our imagination.

Chess is a simple example. At every point, players select a move out of many possible moves. Over a series of moves, the game takes a path through the space of possible chess games. What separates grandmasters is extensive historical experience and knowledge of previous chess games, and incredible imagination for the space of possible moves. They see close to all possible moves at each point, and predict how each one might play out over many steps.

Chess is simple enough that the best humans can do this without any external tools. But it’s probably on or around the limit of complexity that human brains can comprehend. For more complex domains, the true space of possibilities is far beyond our comprehension. We simply don’t have the imagination to consider all scenarios, which limits the pathways we’re able to choose in the present.

Models do. Today that just means exploring language and images. But tomorrow it will include much more. The significance of visualising latent spaces is that whatever the domain, we inherit the model’s “world model” as our own. We see through it’s “eyes” to reveal the space of possible futures, especially the paths we didn’t know existed.

Interstellar’s tesseract helped Cooper see time as a map that he could explore non-linearly. AI interfaces can help us do the same for possibility spaces. The question is — if forcing linear thought via print media transitioned a civilisation from alchemy to enlightenment, then what happens to a society that’s forced to think non-linearly?